General David Petraeus, former CIA chief, does not see much cause for optimism regarding a deal with Iran: ‘We cannot allow them to be on the brink of having a nuclear weapon’; believes ‘threat from al-Qaeda remains very real, and it would be a mistake to think … al-Qaeda has gone away. It hasn’t’; and dismisses the idea that Syria’s Assad can be part of the solution: ‘He isn’t; he is a big part of the problem.’

Retired US general David Petraeus doesn’t hide his concern for the situation. Almost every situation. The situation in Syria, the situation in Iraq, the situation in Libya, the situation with respect to al-Qaeda and vis-à-vis Islamic State. Petraeus is also worried about Iran.

Like Benjamin Netanyahu, he, too, has a hard time trusting the regime in Tehran; but the former head of the CIA does differ with the position of the Israeli prime minister on one substantial issue – with regards to the chances of a US-Iran deal actually being signed.

David Petraeus (Photo: Motti Kimchi)

“Despite the willingness of the Obama administration to meet the Iranians more than halfway, I think the prospects for a breakthrough are still less than 50-50,” Petraeus says. “Ultimately, I have my doubts whether the Supreme Leader will ever agree to roll back components of the nuclear program – which is what any deal would require, even one assessed as favorable to the Iranians – and agree to accept that sanctions relief will be gradual and not immediate. But we shall see.”

Prior to his appointment as head of the CIA, Petraeus, 63, a four-star general (the highest rank in the US Army), served as commander of the NATO forces in Afghanistan. His other four-star assignments included a stint as the head of the US Central Command and the role of commander of the Multi-National Force in Iraq.

Photo: AP)

Following his retirement from the military, Petraeus was viewed even as a possible presidential candidate in the future; but since ending his term as CIA chief in November 2012, he has remained out of the media spotlight and divides his time between lectures and a position at an investment firm. Petraeus granted this special interview ahead of his visit to Israel for the annual conference of the Institute for National Security Studies.

When we ask him if he believes Iran is trying to produce a nuclear bomb (as Israel claims), or truly is focused on developing its nuclear program for civilian purposes only, his carefully worded response reflects his sweeping mistrust of the statements coming out of Tehran.

“To accept that Iran’s nuclear ambitions over the years have been exclusively peaceful would require a willing suspension of disbelief,” he says. “This isn’t just a US or Israeli judgment. The International Atomic Energy Agency has extensively documented the so-called ‘possible military dimensions’ of the Iranian program, which clearly indicate that – at least until a few years ago – the Iranians were conducting activities whose only rational explanation is that they wanted a nuclear weapons capability.

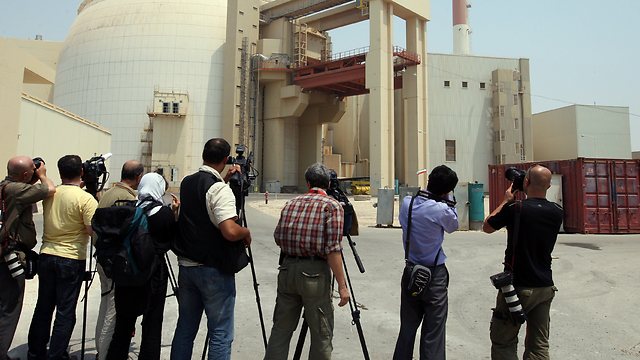

Bushehr reactor – Iran (Photo: AFP)

“Now it’s still an open question whether the Iranian leadership has made the formal decision to build an actual bomb, or whether they would be content waiting on the threshold – with the capability to do so, but at least a few screwdriver turns short of a working weapon. History suggests, however, that countries that get to that threshold do not stay there. And regardless, based on everything we know and see about the Iranian government, we cannot allow them to be on the brink of having a nuclear weapon. For all intents and purposes, that is a distinction without a difference, including with respect to its implications for regional proliferation.”

Netanyahu claims that the vast part of the Iranian nuclear project must be dismantled. He believes that this is the only way to ensure that Iran will not renew its efforts in the future. On the other hand, Iran will never agree to this prerequisite. Where do you see a possible solution?

“To my mind, a ‘good deal’ needs to bolt the door on the Iranians getting a nuclear weapon. In this respect, certainly large swaths of the program need to be dismantled or at least altered. I don’t know that this requires an end to enrichment, but certainly it would seem to me that there need to be substantial limitations on how much enriched material Iran can possess and the percentage to which they can enrich, as well as restrictions on the research, development, and deployment of new, more sophisticated models of centrifuges, and so forth. An extremely robust inspections program is also necessary – going beyond the Additional Protocol of the Non-Proliferation Treaty. In fact, the inspections regime is, in my mind, the most critical component of a deal.”

How would you define the level of cooperation between the United States and Israel?

“Being out of government for more than two years, I cannot comment about the specifics of what is happening now, but my sense is that our military and intelligence cooperation remains very robust – as it should, and as I would hope it will always be.”

The danger of the lone wolves

But with all due respect to the Israel-US relations and the Iranian issue, the biggest challenge by far facing the US military and intelligence community – in both of which Petraeus held very senior position – is the war on terror. Almost a decade and a half has have gone by since the attacks of September 11, 2001, and then-US president Bush’s declaration of war on global terrorism, and Petraeus believes the fighting is far from over. In fact, he says, the toughest part may still lie ahead.

Photo: MCT

“We’re in the midst of what clearly is a long struggle,” he says. “There are no shortcuts to success, no single measure that we can take that will eliminate the danger in one fell swoop.

“In the 13 years since the September 11 attacks, we have achieved some notable successes, including the removal of some of al-Qaeda’s most important leaders from the battlefield. We have made progress in degrading so-called ‘core al-Qaeda’ in its sanctuary in the tribal areas of Pakistan, and we have prevented another large-scale attack from taking place on US soil. These are not minor accomplishments.

(צילום: AFP)

“At the same time, the adversary we face is resilient, adaptive, and determined. As core al-Qaeda has been degraded, we have seen the rise of affiliates in places like Yemen and Africa, and of offshoots like Islamic State – some of which have the potential to eclipse core al-Qaeda in their lethality. This has also encouraged a worrisome competitive dynamic among rival Islamist extremist groups. There is also the growing danger in the West posed by so-called ‘lone-wolf’ terrorists – individuals who’ve been radicalized, often through online contacts, who carry out comparatively small-scale yet still deadly attacks.

“Above all, we need to recognize that we are not just battling a monolithic organization – an entity that can be degraded and eventually destroyed – but also an ideology. It is this ideology of violent Islamist extremism that animates the followers of al-Qaeda and Islamic State, and that ultimately needs to be discredited and discarded in order for us to be successful in this conflict.”

Photo: AFP

When it comes to the rise of Islamic State, the “new star” in the terror skies, Petraeus speaks in relatively moderate terms; the general warns against portraying the murderous Sunni organization as invincible, but admits that on this front, too, against the radical Islamists, the battle is far from over.

Did the blow suffered by al-Qaeda create the vacuum into which Islamic State moved?

“No, that would be a profound misreading of the dynamics that created the so-called Islamic State. Islamic State – or Daesh, as our Arab allies call them – emerged out of the remnants of al-Qaeda in Iraq and an al-Qaeda affiliate that came into being during the Iraq War but that was effectively defeated during the surge. Al-Qaeda in Iraq was then given a new lease on life by two developments.

ISIS forces (Photo: EPA)

“The first was the civil war in Syria and Bashar al-Assad’s campaign of absolutely relentless violence against his own people, which created a radicalizing dynamic among the Sunnis of Syria and made them susceptible to the message of violent Islamist groups like al-Qaeda in Iraq and later Islamic State. Assad deliberately targeted moderate rebel groups, while ignoring the growth of Islamist extremists, precisely because he wanted the conflict to become a choice between him and something that appeared to be even worse. That is part of the context out of which Islamic State emerged.

“At the same time, Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki in Iraq grew increasingly sectarian and authoritarian after the departure of US forces. As a result, many Iraqi Sunnis – whose reconciliation and reintegration had been at the heart of the surge – grew increasingly angry and disenfranchised, which gave space for Islamic State to get a growing foothold in Iraq too.”

Is the West’s war on Islamic State proving to be an effective one?

“I think we have made progress against Islamic State in Iraq in recent months, and we will make more over the coming months. Despite the blitzkrieg-like Islamic State assault across Iraq last year, we shouldn’t make the mistake of overestimating Islamic State or underestimating the Iraqi security forces. Islamic State elements are not ten feet tall; they can be defeated.

“Militarily, the coalition has been hammering Islamic State with airstrikes, whose impact – both material and psychological – is considerable. And we also have sent several thousand US troops back into Iraq, working with the Iraqi security forces and the Kurdish Peshmerga, which is necessary. We have also seen some positive political developments in Iraq over the past few months, with the emergence of a more inclusive, less sectarian government, which will give Sunnis a greater measure of support and responsibility for security in their own communities.

Bashar al-Assad (Photo: Reuters)

“In the medium- and long-term, when it comes to Iraq, I frankly worry less about Islamic State than I do about the Iranian-backed Shia militias. If Islamic State retreats from Mosul tomorrow, we do not want the primary beneficiary to be Iran or its proxies in Iraq – but there is a very real danger that is what could happen if we are not careful.

And in Syria?

“Syria is a very different matter. In order to defeat Islamic State there, it will be necessary to foster the development of an effective indigenous ground force that can challenge their control over territory in Sunni majority areas, and a political process that gives Syrian Sunnis a reason to stand up against the extremists. Unfortunately, neither of these things is right now in place.

“We should also be very cautious about any notion that Bashar Assad can become part of the solution. He isn’t; he is a big part of the problem – not the least of which is that his presence attracts many of the foreign fighters to Syria.

“We need to recognize that Islamic State is positioned to make inroads elsewhere in the Middle East. We see affiliates of Islamic State gaining ground in Libya, which ought to be a place of enormous concern, and making inroads in the Sinai, Algeria and Yemen.

Child holds mortar in Idlib, Syria (Photo: Reuters)

“The dynamic in Libya – a worsening, multi-sided civil war in which foreign countries are backing rival groups – is particularly troubling, as it has some eerie parallels to the situation in Syria two or three years ago. If the current trajectory continues, it is a safe bet that Islamic State could gain a great deal of ground there. And as in Syria, the longer the conflict there grinds on, the worse our options in Libya will become.”

A letter to 160,000 soldiers

If there’s one conclusion that the veteran general has drawn from more than a decade of war it’s the fact that there is no way of defeating international terror organizations without tackling the root causes of their emergence to begin with. And this means not only fighter planes and sophisticated weapons, but also affecting social and economic change and a shift in regional dynamics.

“I think we have found that the most effective way to combat al-Qaeda – indeed the only effective way to combat al Qaeda and its affiliates – is through a comprehensive approach that brings to bear all the elements of national power, and that mobilizes others to join the fight against them as well,” Petraeus says.

“I’ll give you an example,” he continues. “During the surge in Iraq, al-Qaeda’s affiliate there was decimated. We were able to do this not just because we relentlessly targeted its leaders and fighters – although that was indispensable – but also because we attacked their network on multiple other fronts too – by providing security that separated al-Qaeda from the population; by encouraging political reconciliation and reintegration so that the Sunnis, who were the base of support for al-Qaeda in Iraq, had an incentive to break with al-Qaeda Iraq and side with the government; through financial warfare that deprived al-Qaeda in Iraq of the means to fund itself; and so on.

“Another lesson from the past decade is that it is necessary to maintain pressure on terror networks, because they’re resilient. If we pull back, they will regenerate themselves. That, unfortunately, is part of the story of what happened in Iraq – and it could happen in Afghanistan and Pakistan too.

Photo: AFP

So is ‘core al-Qaeda’ still active and viewed as a threat?

“Absolutely. As I mentioned, al-Qaeda is a resilient and regenerative network. Core al-Qaeda, al-Qaeda’s leadership in the rugged tribal regions of Pakistan, has been degraded because of persistent pressure that has been put on its sanctuary in tribal Pakistan. If that pressure is reduced or removed, the odds are considerable that it will grow back.

“Apart from core al-Qaeda, al-Qaeda affiliates around the world also remain a deadly serious threat. Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula – based in Yemen is responsible for concocting some of the most fiendishly clever and creative terror plots against the West in recent years. They also regularly produce some very slick English-language propaganda that appears to have played a role in inspiring lone-wolf attacks in Europe and North America.

“So yes, the threat from al-Qaeda remains very real, and it would be a mistake to think that with the rise of Islamic State, al-Qaeda has gone away. It hasn’t.”

What are your views on targeted killings? Israel has come under harsh criticism from the international community for its use of targeted killings, but perhaps they would be effective in the fight against Islamic State.

“There are two separate questions here. The first is whether targeting killings are legally permissible. The second is whether they are strategically wise.

Photo: IDF

“On the first point, there is no doubt in my mind that the US is in a state of armed conflict with al-Qaeda and associated forces, and likewise with Islamic State. From the perspective of international law, then, it is permissible for the US to target enemy belligerents. It is also a valid exercise of our self-defense rights under the UN Charter to target individuals who are actively plotting to kill our citizens – and who are located in places like northwest Pakistan or tribal Yemen, where they are beyond the reach of local authorities, and where capture isn’t a realistic option.

“I also think it is worth stressing: The ambitions of groups like al-Qaeda and Islamic State aren’t geopolitically conventional, in the sense that they do not simply want territory and power. Their ambitions are totalitarian and even genocidal, and in that respect, they are quite different from the other adversaries we confront. We have a special responsibility to prevent such groups from establishing sanctuaries, plotting attacks and inflicting their ambitions on the world.

“At the same time, I think it is important to recognize that the targeting killing of terrorists is a tactic; by itself, it is insufficient to defeat al-Qaeda or other terror networks. That requires a more comprehensive approach that attacks the network from multiple directions at once, including efforts to address the underlying causes that allow these organizations to draw support.”

When Petraeus is asked to comment on the Congressional Report that harshly slammed the interrogation methods employed by the CIA against al-Qaeda prisoners, we sense in his response a hint of criticism against the organization he once oversaw.

“In May of 2007, not long after I became commander of Multinational Forces in Iraq, I sent a letter to over 160,000 soldiers, sailors, airmen, Marines and Coast Guardsmen whom I was privileged to lead. At the time, it was the height of the surge and our forces were engaged in some of the most difficult, intensive ground combat since Vietnam. American casualties were also at the highest level since that conflict.

“In the letter, I wrote that while we were engaged in combat and had to pursue the enemy ruthlessly, we also had to observe the standards and values dictating that we treat noncombatants and detainees with dignity and respect. It was my belief then, and it remains my belief now, that adherence to our values distinguishes us from the enemy, and that we – not our enemies – must occupy the moral high ground.

“I am convinced that the path to prevail against the enemy that attacked us on 9/11, and with which we continue to be at war, requires that we not lose sight of our own deepest values. While our enemies routinely act without conscience, we cannot afford to do so.”

Bad news for Russia

During Petraeus’ term as head of the CIA, the Middle East experienced the so-called Arab Spring – or as others may put it, the Muslim Winter.

“The uprisings that began to sweep across North Africa and the Middle East in 2011 were long in coming,” he says. “They were the product of deep accumulated frustrations about corrupt and repressive governance. Since 2011, however, the countries of the Arab Spring have gone in very different directions.

“In Tunisia, where the Arab Spring began, we have seen the emergence of a genuine, if still fragile, pluralistic democracy. In Libya, on the other hand, the destruction of the Gaddafi regime left a complete power vacuum and the result was chaos, and now an accelerating civil war. In Egypt, we have seen the reemergence of a military-led government, on much the same model that has governed the country for decades. In Yemen, there was what appeared to be a relatively successful transition for a period of time – with a national dialogue in which all parties were participating and a relatively unified international position – but that now has unraveled.

“Stepping back from the specifics of the different countries, a few broad conclusions might be drawn. The first is that – very much in keeping with historic patterns associated with revolutions – the people who were responsible for leading the uprisings in most of the Arab Spring countries have not been the primary beneficiaries of them. The second is that the weakening – and in some cases, the disintegration – of government authority in many Sunni Arab states has been exploited by well-organized outside forces, in some cases groups like al-Qaeda and Islamic State, and in others the Iranians. Unfortunately, they have been the primary beneficiaries of the Arab Spring in too many places.”

Petraeus makes particular note of the violent internal strife in Libya, where the casualty numbers are mounting, and he singles it out as a country on the verge of falling into the hands of radical elements.

“For several years after the fall of Muammar Gaddafi, Libya was in chaos, with numerous armed groups jockeying for power and resources,” he says.

“What is happening now, however, is even more worrisome—an accelerating civil war in which different militias are backed by outside powers and engaged in what all sides are depicting as an existential and irreconcilable struggle. The primary beneficiaries are groups like al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb and Islamic State, which – just as in Syria – knows how to operate in an atmosphere of chaos and draw strength and support from the radicalizing dynamic of violence.

“Also at risk are neighboring countries – Tunisia, Algeria, Egypt, and the Sub-Saharan African states and beyond, which are threatened by the spillover of weapons and fighters and overall instability from Libya.”

Together with showering Saudi Arabia with praise (“It has been very good to see the Saudis participating courageously in the military coalition against Islamic State… Saudi Arabia is also a critical bulwark against the other great danger in the region, which is the Iranian government and its expansionist ambitions”), Petraeus ends with another pessimistic assessment, with respect to Russia this time.

“Regardless of the fate of the recently-declared Minsk II agreement in Ukraine, I think the West is entering into a period of what is likely to be extended competition and tension with Moscow,” he says. “Geopolitically, President Vladimir Putin is behaving in many respects like a traditional Russian ruler trying to reestablish regional dominance over his new abroad.

“This has been building for some time – and it is unfortunate for all sides, but most of all for Russia, which I think will emerge from this confrontation poorer, weaker and less stable.”