Last week, on his return from a tour of the Holy Land, former Governor of Arkansas and Republican presidential nomination candidate Mike Huckabee said to The Washington Post that “there’s really no such thing as the Palestinians.”

“The idea that they have a long history, dating back hundreds or thousands of years, is not true,” Huckabee continued, citing one of the tour’s speakers, Zionist Organization of America president Morton Klein.

Huckabee’s comments are far from the first on the issue from a United States politician. “There was no Palestine as a state,” former House Speaker Newt Gingrich told the Jewish Channel when running for president in 2011. “It was part of the Ottoman Empire. I think that we’ve had an invented Palestinian people who are in fact Arabs.”

It is not often that American presidential candidates make public pronouncements about the historical origins of national identities, but the Palestinian identity is a unique case. It has long been the source of much controversy and mystery, raising the question of when the Arabic speakers of Palestine first began calling themselves Palestinians.

The concept of a Palestinian people had never included Zionists, not in English and certainly not in Hebrew or Arabic.

THE FIRST PALESTINIANS

Based on hundreds of manuscripts, Islamic court records, books, magazines, and newspapers from the Ottoman period (1516–1918), it seems that the first Arab to use the term “Palestinian” was Farid Georges Kassab, a Beirut-based Orthodox Christian who espoused hostility toward the Orthodox clerical establishment but sympathy for Zionism. Kassab’s 1909 book Palestine, Hellenism, and Clericalismfocused on the status of Greek Orthodox Christianity in Palestine, but noted in passing that “the Orthodox Palestinian Ottomans call themselves Arabs, and are in fact Arabs,” despite describing the Arabic speakers of Palestine as Palestinians throughout the rest of the book.

The term “Palestinian” soon caught on: In 1910, an anonymous contributor to the Haifa-based paper al-Nafir praised an Egyptian writer for acknowledging that Palestinians had made significant literary contributions to the bourgeoning intellectual atmosphere of the age, but criticized him for failing to mention the Palestinians by name. In 1911, the Orthodox Christian Najib Nassar from Haifadescribed himself and others from Palestine as Palestinians in his Haifa-based newspaper, al-Kamil. So too did the Muslim Jerusalemite Muhammad Musa al-Maghribi around the same time in his Jerusalem-based newspaper, al-Munadi, noting that the paper would cover only news relevant to the Palestinians. In June 1913, the concept of a Palestinian identity began forming in the media, prompting Ottoman parliamentarian and Muslim Jerusalemite Ruhi al-Khalidi to write an article titled “The Palestinian Race” for the paper Filastin, arguing that Zionists were attempting to create an exclusionary society in Palestine.

HISTORY MISUNDERSTOOD

In the wake of Gingrich’s 2011 statements, members of the media went searching for answers to the mystery of the origins of the Palestinians. The Guardian ran a piece stating that “most historians mark the start of Palestinian Arab nationalist sentiment as 1834, when Arab residents of the Palestinian region revolted against Ottoman rule.” In fact, few if any historians think that the 1834 revolt had much to do with Palestine or the Palestinians. Rather, the event was a revolt in support of Ottoman rule, against the policies of the Levant’s new Egyptian occupiers who had levied high taxes, conscripted young men into the army, and abolished erstwhile privileges that Muslims had had over their Christian neighbors.

Fox News also tried to contextualize Gingrich’s comments, stating, “Palestinians never had their own state—they were ruled by the Ottoman Empire for hundreds of years, like most of the Arab world. When the Ottoman Empire collapsed … the British … took control of the area, then known as British Mandate Palestine. During that time, Jews, Muslims and Christians living on the land were identified as ‘Palestinian.’ But modern-day Palestinians bristle at the implication that they were generic Arabs. … [T]hey, for the most part, identify themselves as Palestinians, just as the Lebanese, Jordanians and Syrians also identify themselves with a specific national identity.”

Strictly speaking, this is true, even if no good historian would ever write something so obfuscating. The word “Palestinian” in English, and “Filastini,” its Arabic equivalent, were both used to describe any citizen of the British Mandate of Palestine (1920–1948), and thus Zionists did call themselves “Palestinian Jewry,” or “Palestinian subjects,” in English (although not Hebrew), before 1948. Zionists have often touted this point as revelatory, arguing that the terminology undercuts the idea of a unique Palestinian identity. But the concept of a Palestinian people, in contrast to a Palestinian civic identity, had never included Zionists, not in English and certainly not in Hebrew or Arabic. It was a term reserved for the Arabic-speaking peoples of Palestine, and it appeared frequently in Arabic books, magazines, and newspapers throughout the Mandate period.

SEMANTICS AND SOUTHERN SYRIA

A prevailing counternarrative to assertions of Palestinian identity rests within the realm of geography: Michael Assaf was one of the first Zionist historians to lend credence to the idea of Palestine. He claimed in his 1930s book The Arab Movement in Palestine that the Land of Israel had never existed in Arab history as a unit in and of itself. Muslim Arabs, instead, considered it part of the land of Sham, or so Assaf thought. The Arabs emphasized the name Southern Syria, he argued, to show that the land was part of Arab Syria, rather than a special or distinguished land.

The controversy would not reach front-page headlines for another three decades, until the newly elected Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir stated in 1969 in an interview with The Sunday Times that “there were no such thing as Palestinians.” “When was there an independent Palestinian people with a Palestinian state?” Meir asked. “It was either southern Syria before the First World War, and then it was a Palestine including Jordan.”

Is Palestinian identity an invention? The answer, however, is self-evident—of course it is.

Southern Syria first appeared in Arabic sources in 1918, shortly after King of the Arab Kingdom of Syria Faysal I revolted against the Ottoman Empire in 1916 during the First World War and established an Arab Kingdom in Damascus in 1918, which he ruled for the better part of two years. Many Arabs in Palestine thought naively that if they could convince Palestine’s British conquerors that the land had always been part of Syria—indeed, that it was called Southern Syria—then Great Britain might withdraw its troops from the region and hand Palestine over to Faysal.

Southern Syria was therefore born out of the preference of Palestine’s Arabs to live under Arab rule from Damascus, rather than under British rule from Jerusalem—the same British who, only a few months earlier, in 1917, had declared in the Balfour Declaration their intention to make Palestine a national home for the Jews. Palestinian Arab attempts to join Syria were shattered when the French deposed Faysal in July 1920, taking Syria for themselves.

Since then, Southern Syria has been remembered only sporadically, and for political purposes. Arabs who believed that an Arab state in all of Greater Syria was the best way to stem Zionist immigration and land purchases occasionally embraced the term, while Zionists such as Assaf and Meir revived it to show that the Arabs never cared much for Palestine. Of course, it was precisely Arab concern about Palestine, and desire to shield it from British imperialism and Zionist colonization, that gave birth to the idea of a Southern Syria in the first place.

WHAT’S IN A NAME

The controversy over Palestinian identity continues unabated. In the early 2000s,French and Italian airline pilots welcomed their passengers to Palestine upon arrival to Tel Aviv’s Ben-Gurion Airport, and were summarily told by Israeli authorities they would not be flying to Israel again. In 2013, Google changed its “.ps” homepage tagline from the Palestinian Territories to Palestine, immediately provoking Israeli condemnation. For many, Google hadn’t gone far enough, as one contributor to Change.org started a petition titled “Add Palestine to Google Maps.”

Ultimately, the war of words found its likely home on Twitter. Traffic with the hashtag #there_was_no_palestine flooded the site in April 2014. Some messages supported the claim, while others co-opted it with photos and newspapers clippings of Palestine from the early 1900s.

The decades of debate all lead to a central question: Is Palestinian identity an invention? The answer, however, is self-evident—of course it is. American, Chinese, German, and Israeli identities are inventions too. All national identities are invented. Nations do not exist in nature; they exist only in our minds.

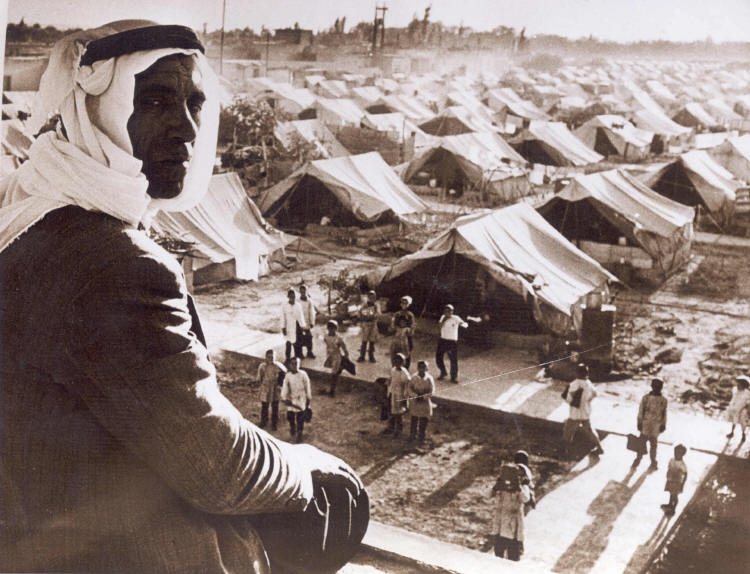

The question then becomes why Republican presidential candidates, Israeli prime ministers, and Western pundits offer constant reminders that Palestinian identity is an invention if all concepts of nationality and identity are human-engineered fabrications. For that, we have those who have spent their careers trying to keep Palestine and the Palestinians off the map and out of sight to thank.