The Biden administration is pressuring Israel to define its plan for “the day after.”

This is a bit like demanding America have a plan for postwar Japan weeks after Pearl Harbor.

But worse, Washington insists the end goal of Israel’s war be the establishment of a Palestinian state.

Understanding how unlikely Israel is to accept this suicidal proposal, Secretary of State Antony Blinken suggests it turn Gaza over to a United Nations peacekeeping force or other multinational presence.

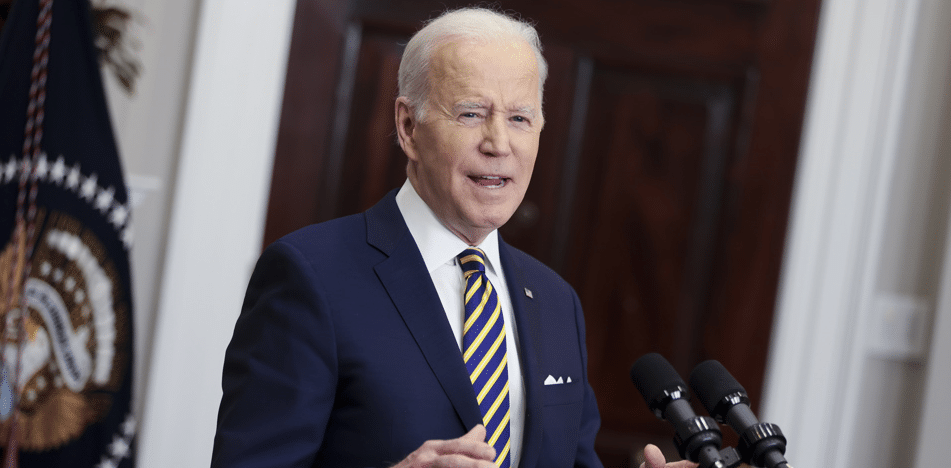

President Biden just called for the “international community” to provide “interim security measures.”

The United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon literally has “interim” in its name and has been failing at its job since 1978.

The idea of international forces in Gaza repeats decades of mistakes.

In every single case, UN forces and agencies failed to provide Israel any security and were coopted and used by its enemies.

After 1956’s Suez War, the Security Council created the United Nations Emergency Force to keep the peace on Israel’s border with Egypt.

Right before the Six-Day War a decade later, Egypt demanded the peacekeepers leave — and they obliged.

The UN Truce Supervision Organization, a Jerusalem-based force, fled when the Jordanians attacked Israel during that war, but the mission remains today, publishing reports critical of Israel and using its diplomatic plates to gum up parking in Jerusalem.

The UN Disengagement Observer Force was created after 1973’s Yom Kippur War to keep the Syrian front quiet.

When Islamist militias moved into the demilitarized zone during the Syrian Civil War, the international forces predictably responded by pulling their troops out.

Then there’s that United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon, which did nothing to prevent the Palestine Liberation Organization’s and then Hezbollah’s innumerable attacks on Israel, leading to two wars.

After 2006’s Second Lebanon War, it was used again as diplomatic fig leaf to bring about an Israeli withdrawal.

In exchange, the Security Council required UNIFIL to disarm Hezbollah in the country’s south.

Yet Hezbollah’s arsenal of rockets and missiles has grown more than tenfold since then.

It’s ridiculous to talk about an international presence in Gaza when rockets from Lebanon rain down on Israeli homes under the nose of the largest peacekeeping force outside Africa.

UN missions are particularly problematic because of the deep institutional bias of the organization, which has been on full display in this conflict: The secretary-general has made excuses for Hamas’ genocidal attack.

And UN institutions in the Palestinian territories are actually taken over by terrorists, with the UN Relief and Works Agency actively collaborating with or under the influence of Hamas.

Blinken also suggested the possibility of a non-UN international force. Such ideas don’t have a better record.

When Israel withdrew from Gaza in 2005, it agreed on a European Union force to monitor border crossings and prevent weapons from being smuggled in.

But when Hamas took power two years later, the EU observers took off.

Israel also insisted it must continue to patrol the Egyptian border but was pressured into giving this role to Egypt — which allowed Gaza to be turned into the arsenal against Israeli cities it is today.

The same story played out in the West Bank. In 2001, after the assassination of an Israeli government minister, Washington persuaded the Palestinian Authority to arrest and imprison the guilty terrorists.

Israel was concerned this would be a sham, so America and Britain agreed to have their police officials supervise the prison.

Four years later, Hamas threatened to liberate the prisoners, leading both countries to promptly remove their personnel to keep them out of harm’s way.

No foreign presence will be willing to do the grinding work of ensuring Hamas is not reconstituted, a mission that would risk troops’ lives and potentially cause geopolitical tensions.

When even America tolerates Iranian proxies’ drizzle of attacks on its bases in the Middle East, Israel cannot expect any outside actor in Gaza will stand up for the Jewish state’s security.

Even more disastrous would be turning Gaza over to Mahmoud Abbas’ Palestinian Authority.

It has actively cheered Hamas, and its Fatah faction even participated in the Oct. 7 massacre.

If Fatah wanted a claim to govern Gaza, it should have fought against Hamas, not alongside it.

If the goal is ensuring Israel’s security, history rules out both international forces and Palestinian factions. But it also points towards what could work.

From 1967 to 2005, the Israeli army operated freely in Gaza.

As a result, terrorists could not acquire rockets that could strike Tel Aviv or organize massive invasions of Israel.

All that began when Israel completely evacuated Gaza and gave Fatah control.

Similarly, attacks like this have not come from the West Bank because Israel maintains security control and control of the borders.

Israel left Gaza in 2005 because of (mistaken) international criticism of its “occupation”; for its trouble, it now gets falsely accused of genocide.

Biden’s proposals have nothing to do with protecting Israel from future genocidal attacks and everything to do with not alienating his progressive base.

But if Israel heeds them, it means the Jewish state loses even if it wins.

Eugene Kontorovich is the director of the Center for the Middle East and International Law at George Mason University Scalia Law School.