http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2011/12/14/the_end_of_fayyadism

The “Arab Spring” may be pushing the Middle East toward transparency and more representative government, but the Palestinian Authority is bucking the trend. Prime Minister Salaam Fayyad, perhaps the only Palestinian leader who earnestly sought to usher in an era of good governance, is now under siege from political rivals. But instead of providing him the support he needs to weather the storm, Washington has chosen to stand on the sidelines.

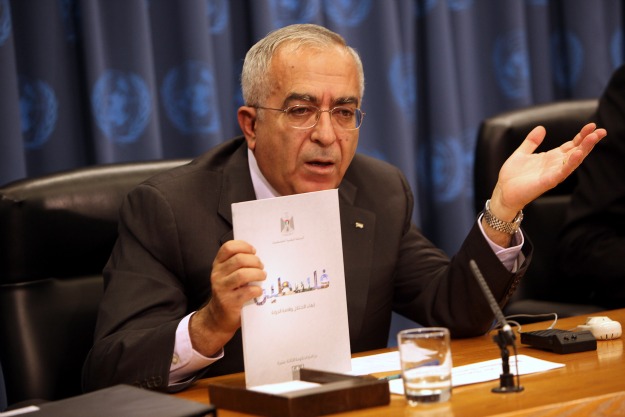

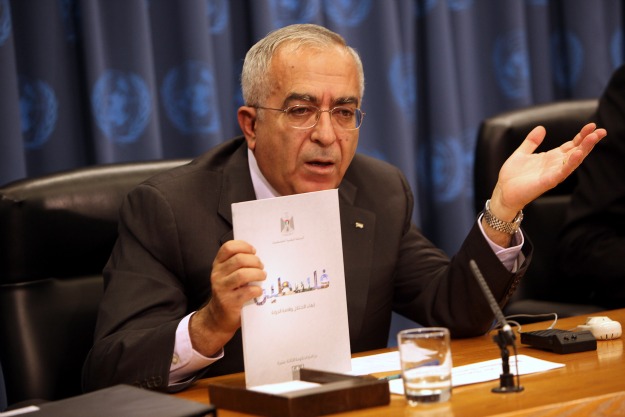

“Fayyadism” was once hailed in Washington’s corridors of power — and by the New York Times’s Tom Friedman — as a refreshing alternative to the governing philosophy of other Middle Eastern regimes. As Friedman wrote in 2009, “Fayyadism is based on the simple but all-too-rare notion that an Arab leader’s legitimacy should be based not on slogans or rejectionism or personality cults or security services, but on delivering transparent, accountable administration and services.”

President Mahmoud Abbas, however, has other ideas for the Palestinian Authority. In recent years, he has methodically marginalized Fayyad and used cronyism to consolidate his personal power.

Abbas’s latest step has been to orchestrate a series of trials against the prime minister’s top officials. On Nov. 29, the Palestinian prosecutor-general charged Economy Minister Hassan Abu Libdeh with corruption, paving the way for him to stand trial this month. The charges — breach of trust, fraud, insider trading, and embezzlement of public funds — date back to Abu Libdeh’s tenure as director of the Palestinian Capital Market Authority in 2008. Earlier this year, the newly formed Palestinian Anti-Corruption Commission also charged Agriculture Minister Ismail Daiq with corruption. Daiq is still awaiting trial.

In the Palestinian Authority, corruption probes aren’t launched unless the president wants them launched. In this case, Abbas has engineered these latest scandals to discredit Fayyad and cast doubt on the prime minister’s ability to deliver on his celebrated mandate of countering corruption. After all, the corruption goes to the highest levels of the Palestinian Authority, and the officials in question were appointed by Fayyad himself.

While the merits of these cases are yet to be determined, they are not designed to rid Palestine of corruption. Rather, by ousting ministers and hobbling Fayyad, Abbas creates an opportunity to replace them with figures more to his liking.

Abbas makes the major decisions impacting Palestinians out of his sprawling Muqata compound in the West Bank city of Ramallah. Fayyad, meanwhile, works with a skeleton crew in a modest office nearby. According to officials who work with them, the two figureheads of the Palestinians are barely on speaking terms. Fayyad has become a glorified accountant, leveraging his strong relationship with international donors to collect checks that ensure his government can continue to pay salaries — while Abbas pursues a provocative foreign policy that endangers those sources of funding.

Early this year, when Abbas began openly angling for international recognition of Palestinian statehood at the United Nations — a finger in Washington’s eye — Fayyad opposed him. Although Fayyad’s efforts were part of the original plan in 2009, as it became clear that the unilateral approach was infuriating Washington and prompting Congress to mull a cutoff in aid, he openly questioned the success of the endeavor. As he recently remarked, “This is not the state we are looking for.”

In November, when Abbas entered into negotiations to form a unity government with the terrorist group Hamas — a deal that could prompt a full cut in U.S. funding — Fayyad stood ready to resign. And while he claimed that he was prepared to step aside in the name of “national unity,” Fayyad has since gone on record as refusing to serve the future Hamas-Fatah coalition government in any capacity.

Now that both Abbas-led ventures have been tabled for the time being, the president has manufactured these new corruption probes against members of the Fayyad cabinet.

This is not to say that a corruption probe is ill-advised. One should be launched — but it should focus on Abbas and his immediate family members, who have reportedly grown rich from no-bid contracts. Most notable, perhaps, was the 2010 Wataniya cell phone tender that reportedly yielded fruit for the president’s sons, Yasser and Tarek. A future probe should also focus on the members of Abbas’s inner circle and the centralized system that grants them position, money, and power.

Unfortunately, the State Department and the White House are loath to take these steps. President Barack Obama’s administration is not blind to corruption in Ramallah and the erosion of Fayyad’s power, but it rightly fears that weakening Abbas — let alone toppling him — will lead to a power vacuum from which only Hamas will benefit.

After all, it was Hamas that claimed a resounding victory in the 2006 legislative elections, which were undisputedly free and fair, prompting Washington to throw its full backing behind Abbas. He has since become an unlikely centerpiece of U.S. policy and a counterweight to the Islamist group that also happens to be an Iranian proxy. In the absence of a viable alternative, the Palestinian leader has also won a remarkably free hand in his domestic and international battles.

Abbas knows that Washington values his ability to fend off Hamas more than it does Fayyad’s ability to govern. This explains why he feels unencumbered to test Washington’s patience, both when it comes to political reform in Ramallah and the statehood bid at the United Nations. It also explains why Washington has stood by silently as Fayyad has struggled in vain to maintain his dwindling authority.

To be sure, Washington still pays lip service to the potential of Fayyad’s reform agenda, but the White House knows the prime minister’s days are numbered. According to several of Fayyad’s allies, American diplomats have reportedly written him off.

The end of Fayyadism translates into another expensive taxpayer investment gone wrong in the Middle East. It means the end of an era that offered hope for political reform for the Palestinians. With little hope for change, it also marks the beginning of a new and dangerous period in the Palestinian-Israeli conflict.