http://www.israelnationalnews.com/Articles/Article.aspx/10690#.To6od5sr2so

Between Purim and Pesach in 1973, while learning at Pardes Institute in its first year, as I was just crossing the Rubicon to become an observant Jew, the opportunity presented itself to visit Kibbutz Kfar Etzion for the first time.

Between Purim and Pesach in 1973, while learning at Pardes Institute in its first year, as I was just crossing the Rubicon to become an observant Jew, the opportunity presented itself to visit Kibbutz Kfar Etzion for the first time.

Two friends were in the Nachal Garin [army unit dealing with agricultural settlement, ed.] on the kibbutz.

This Kfar Etzion place had a certain enchantment to it.

A special bar mitzvah present my father gave me was “Siege in the Hills of Hebron”, the story of the gallant fight and massacre of kibbutz Kfar Etzion and the inspiration that the fighters of Kfar Etzion gave to the nascent state of Israel with the battle cry of REMEMBER KFAR ETZION.

Reading that book at age 13 made me think of REMEMBER THE ALAMO that I’d grown up with in the 1950’s, as an avid follower of the battle of Davy Crockett and the Wild Frontier, the first movie brought to the TV screen by Walt Disney..

After leaving a message for my Nachal friends at the public phone of the kibbutz that I was accepting their invite to visit Kfar Etzion for Shabbat, I set off for my first venture into the hills of Hebron, taking a bus that passed Rachel’s Tomb and Bethlehem, winding up in Kfar Etzion after a seemingly endless journey.

Upon arrival, two hours before the Sabbath, entering the Nachal dorms, it was disheartening to discover that the two Nachal friends had gone to Jerusalem, and it was too late to go back to Jerusalem.

As I wandered back to the Kfar Etzion gate to see if there was a way back to Jerusalem. the guard asked me why I seemed so distraught.

After relating what had happened, I was relieved when the guard told me that there was nothing to worry about.

He would have me as his guest for Shabbat.

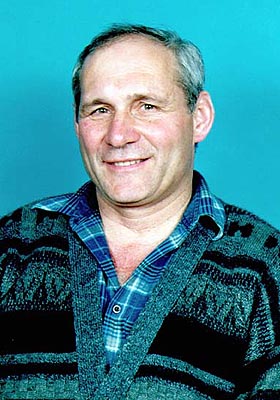

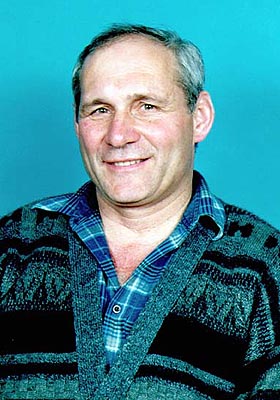

That guard was Hanan Porat, who explained that Kibbutz members took turns guarding at the gate. He apologized for being on duty that night, and hoped that we would have a chance to speak the next day after morning prayers in the synagogue.

At the time, all the kibbutz members ate their Shabbat dinners in the Kfar Etzion dining hall, which had been converted from some kind of Jordanian army barracks, with the insignia of the Jordanian army still on the entry way into the room.

A debate ensued that night over whether guards carrying weapons should wear Shabbat clothes.

The Rabbis in the dining hall quoted all kinds of halakhic sources, and the integration of Shabbat and a frontier outpost seemed very real indeed.

The next day, during Shabbat lunch at the Porat home, Hanan asked how I saw the political situation, to which I responded, matter of factly, that much of my active passion for the past three years in Israel was involvement in the effort to establish an independent Palestinian Arab state and that my thoughts were also based on the rights of the Ger-Toshav, the term for a non-Jew residing amicably in the land of Israel.

Hanan’s response, expressed in a soft tone, calmly and respectfully, was that he had a different perspective, and that he also was concerned about the rights of the non-Jew in the land of Israel, and that a Ger-Toshav must be protected and respected.

Hanan then explained his point of view, which was that statehood, sovereignty and independence would constitute a threat to Israel, since any Palestinian Arab state would be armed and would strive to achieve sovereignty in all of Palestine, and to replace the state of Israel by force of arms.

Our dialogue lasted for seven hours. We only stopped for the afternoon Mincha prayers and continued speaking until the Havdalah ceremony ended the Sabbath.

I raised every possible argument for a Palestinian Arab state, and Hanan responded with counter arguments, always maintaining a level of that could not help but make you listen to the logic of what he was saying.

Hanan worried about Israeli Arabs joining the PLO with their own demand of independence, Hanan worried that Arab refugees would be inspired by a new Palestinian Arab state to demand the return of their homes in Haifa, Tfzat and Jaffa and collective farms built on the ruins of Arab neighborhoods or villages from where Arabs fled in 1948.

The respect which Hanan showed for someone whose perspective was diametrically opposed to his own was a phenomenon to witness.

Twelve years later, after my own intense dialogue with Palestinian Arab leaders, my perspective on Palestinian Arab sovereignty evolved

Whenever I would encounter Palestinian Arab leaders ready for dialogue, I would raise the issues that Hanan Porat had raised during that chance encounter in 1973. And no Palestinian Arab was ready to renege on all of Palestine as the goal, despite the protestations of Israeli peacenicks that the Arabs of course were ready to compromise.

Moving to Efrat in the Etzion bloc in 1985, Hanan Porat almost lost control of his car when he witnessed our young family with a moving truck, en route to a new home in “his” neighborhood. “I thought that you were on the other side”, Hanan Porat would often kid me.

My answer was that I am on the side of the integrity in the dialogue with Hanan Porat.

Hanan Porat represented the best of what it meant to reach out to touch someone, to ask him if he would like to hear another perspective, without a sledgehammer..

Had Hanan Porat yelled at me and insulted me when I sat at his Shabbat table and spoke of the wonders of a Palestinian Arab state, my position may never have changed.

Instead, Hanan Porat planted questions that form the basis of the passion that now energizes my professional life: to warn against the dangers of a Palestinian Arab State.

Hanan Porat, you touched my innermost soul and the soul of everyone to whom you reached out, with the dignity, respect and love that every person deserves when they ask tough questions.