At first glance, Simon Sebag Montefiore’s best seller Jerusalem: The Biography is surely impressive. Media critics as well as Henry Kissinger have showered it with praise, and the BBC devoted a timely three-part TV series to the author, providing invaluable publicity. Indeed, the book is not dull by any standards. Drama abounds – be it in chapter headings (take chapter 5, “The Whore of Babylon”) or in the description of events, such as the Moloch ceremonies in the days of King Menasseh, “the sacrifice of children at the roaster…in the Valley of Hinom…as priests beat drums to hide the shrieks of the victims from their parents” (p. 39). The Muslim invasion is depicted in graphic detail, particularly the battle of 636 CE, which took place “amidst the impenetrable gorges of the Yarmuk River” (p. 172) – although the area through which the Yarmuk flows is in fact more of an open plain.

Renouncing Uniqueness

Sebag Montefiore has clearly invested much effort in conveying his vision of Jerusalem – past, present, and future. The result reflects thoughtful study of many sources relating to different features of the city, and the author certainly recognizes its special status. However, in his apparent desire to deal evenhandedly with the various local religions, he fails to make it clear that it is only for Jews and Judaism that Jerusalem is, was, and has always been the sole spiritual center on earth. This omission is unacceptable. The author rightly refers, if only en passant, to Midrash Tanhuma and the writings of Philo of Alexandria as two examples of this basic, constant belief, unlimited by time or circumstance. The intensity of Jerusalem’s sacred status for Judaism is such that later monotheistic faiths have attempted at various times to gain a foothold in the city, despite their having other, holier places (Mecca and Medina, Rome and Bethlehem). Perhaps recognizing the significance of capturing the “chosen status” of Judaism, they have utilized diverse strategies to prop up their variant “histories,” including reinterpreting Muhammad’s miraculous night visit to the “Farthest Mosque” on the outskirts of Mecca to include a stopover in Jerusalem.

It has always been fundamental for the Jew to appreciate this imbalance, and it cannot be overlooked in any attempt to describe Jerusalem. Sebag Montefiore has downgraded this uniquely Jewish aspect of the city; as far as he is concerned, Judaism’s monopoly on Jerusalem is limited to part 1 of his book, extending until the year 70 CE. Parts 2-8 belong primarily to other faiths and peoples, and the final section of the book, dating from 1898, is titled “Zionism,” as if the re-establishment of Jewish sovereignty is a separate chapter in the history of the city rather than the restorationof a violently interrupted continuum. Significantly, he neglects to emphasize thata Jewish majority has dominated the citywhenever circumstances have permitted,including from the early 19th century onwardwithout interruption; nor does he remind thereader that only when Jews have ruled thecity have all other faiths enjoyed full rights ofworship there.

Historically Dubious These omissions are partially explained by the almost complete absence of references to classic Jewish works compiled in the Land of Israel – despite their obvious relevance in terms of place, time, and subject. Thus, the Jerusalem and Babylonian Talmuds are together accorded a mere four quotations; the output of Jewish historians from Graetz to current Israeli scholars not of the revisionist mode is similarly glaringly absent. In contrast, detailed descriptions of events and individuals taken from non-Jewish sources abound – even when their relevance is historically uncertain or unsound – notably the passages on Jesus in chapter 11. The sole reference to Jesus in Josephus (Antiquities, book 17, 63-64), whom Sebag Montefiore cites among other non- Jewish sources as confirmation of his existence as a historic character, is widely regarded as being of dubious authorship (see Emil Schürer’s History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus, vol. 1, p. 428ff.).

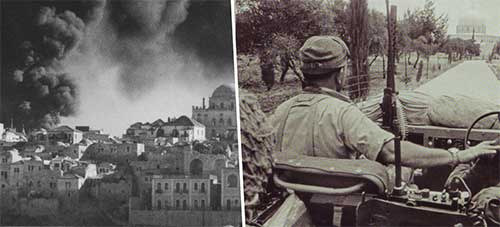

Left: Jordanian forces destroy Jewish landmarks in the Old City of Jerusalem, 1948

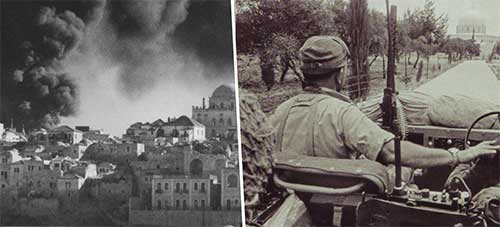

Right: an Israeli jeep approaches the Mosque of Omar during the battle that reunited Jerusalem under Israeli rule, 1967

The reliability of the author’s statement at the opening of the Islam section is similarly questionable: Muhammad is said to have come “to venerate Jerusalem as one of the noblest of sanctuaries” (p. 169). With all due respect, the Koran never mentions Jerusalem, and by beginning his discussion of Islam with the reinterpretation of the passage regarding “the furthest place of worship,” Sebag Montefiore creates a false impression, especially since in Sura 2, the Prophet commands that prayer be directed exclusively to Mecca. The other quotes on page 168 are all from later Muslim sources. The term “Iliya,” a corruption of the pagan name Aelia Capitolina coined by Hadrian, continued to be used by the Muslim conquerors of Jerusalem for a generation or more following Muhammad’s death, with examples from as late as the end of the 10th century. This is the name of the city appearing on the milestones of Caliph al-Malik, who built the Dome of the Rock in the 690s. The name Al-Quds, “The Sanctuary,“ came into common use only in the 11th century, in the context of the struggle between Crusaders and Saracens for dominion over the Holy Land (see Moshe Gil, The Political History of Jerusalem in the Early Muslim Period, p. 10). The anecdote concerning Caliph Omar’s tour of the Temple Mount (p. 175 in Sebag Montefiore’s book) only reiterates the secondary status of Jerusalem in Islam – the caliph rebukes Kaab, a converted Jew, who suggests praying in the direction of the Temple on the mount rather than toward Mecca. As Bernard Lewis has stated in The Middle East, “Much of the traditional narrative of the early history of Islam must remain problematic, whilst the critical history is at best tentative” (p. 51). Why, then, has Sebag Montefiore adopted Islamic accounts regarding this period so readily? Is he perhaps playing to Muslim sensibilities? All this leads us to an epilogue that looks forward, as might be expected from the previous sections, to a permanent division of the city into two capitals for two states, in accordance with current liberal and revisionist dogma. The hope of witnessing such a chapter in the history of Jerusalem rankles coming from a scion of the illustrious Montefiore family, whose philanthropy was once invested in the furtherance of a quite different destiny for the city.

Admittedly, Jerusalem: The Biography provides an enjoyable ride. A more appropriate destination and a less controversial and dangerous route might be preferable, but that, presumably, would require a change of driver.

“Dr, Heny Goldblum is a lawyer and a scholar of history”.