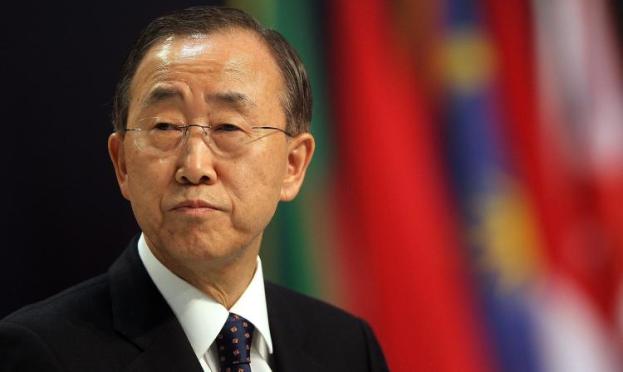

H.E. Ban Ki Moon

Secretary General of the United Nations,

United Nations Headquarters,

405 East 42nd Street,

New York, NY 10017 USA

Mr. Miguel de Serpa Soares, UN Under-Secretary General for Legal Affairs,

United Nations Headquarters

New York, NY 10017

Mr. Stephen Mathias, UN Assistant Secretary General for Legal Affairs,

United Nations Headquarters, Room S-3624,

New York, NY 10017

Mr. Santiago Villalpando, UN Acting Chief, Treaty Section,

United Nations Headquarters, Room DC2-0520,

New York, NY 10017

Mrs. Fatou Bensouda, ICC Prosecutor,

International Criminal Court (ICC),

P.O.B. 19519, 2500 CM,

Maanweg 174, 2516 AB Den Haag,

Netherlands

Excellencies,

I write this letter as a former Legal Officer in the UN Office of Legal Affairs, a former senior member of Israel’s delegation to the 1998 Rome Conference on the ICC and to the preparatory committee involved in the drafting of the ICC Statute, as former Legal Counsel of the foreign ministry of Israel, a regular participant in the General Assembly’s 6th (Legal) Committee and as the former ambassador of Israel to Canada.

In the above capacities, I have been intimately involved both in the extensive legal activity within and for the UN, as well as throughout the various stages in the development and drafting of the ICC Statute and other international legal instruments.

As such, clearly, both the UN and the ICC remain dear to me and close to my heart.

As you are probably aware, the concept of the creation of an independent, permanent International Criminal Court was born following the atrocities of the Second World War and the Holocaust, and representatives of the world’s Jewish communities and the State of Israel were actively involved, since the early 1950’s, in developing the vision and bringing it to fruition. In this capacity, I had the honor to accompany the late Prof. Shabtai Rosenne and the late Judge Ely Nathan and other prominent Israeli international lawyers in the various stages of the negotiation and drafting of the Statute.

However, despite active Jewish and Israeli involvement in the concept and drafting of the Statute, Israel was prevented from becoming party to it, inter alia in view of the injection of politicization into the drafting of the list of crimes set out in Article 8 of the Statute, and specifically the politically motivated manipulation of the drafting of sub-paragraph (b)viii.1

To our great regret, as a “founding father” of the vision, it became evident to Israel that in contravention of the very ideal of an independent juridical institution, the Statute, from the start, was given to politicization, a factor which did not auger well for the future successful functioning of the Court.

Regrettably, our worst fears have recently come to fruition, and the ICC is rapidly and unjustifiably, – and doubtless against its own better interests – being manipulated to become a politicized “Israel-bashing” body, at the initiative of the Palestinian leadership which wrongfully perceives, and widely represents the Court as being their own private judicial tribunal, in order to conduct their political campaign against Israel.

This is borne out in several recent instances in which both the Secretary General and the ICC Prosecutor have been petitioned by the Palestinians to make political determinations at variance with the aims, purposes and very provisions of the Statute.

I refer specifically to the recent Depositary Notifications issued by the Secretary General, Reference C.N.13.2015.TREATIES-XVIII.10 and 13, both dated 6 January 2015, issued following documents transmitted by the Palestinian leadership to the Secretary General on 2 January 2015, requesting accession to the Rome Statute, and other treaties.

These Depositary Notifications acknowledged that:

“The [ICC] Statute will enter into force for the State of Palestine on 1 April 2015 in accordance with its article 126(2)” and

“The Agreement [on the Privileges and Immunities of the ICC] will enter into force for the State of Palestine on 1 February 2015 in accordance with its article 35(2).”

These notifications cite the respective articles in both documents, which refer to “each State ratifying, accepting or acceding to this [Statute][Agreement].”

With respect, it would appear that in so issuing the above depositary notifications, the Secretary General has acted ultra vires a number of essential and well-established requirements concerning the functions of a depositary:

- Article 76(2) of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 19692 according to which:

“The functions of the depositary of a treaty are international in character and the depositary is under an obligation to act impartially in their performance. In particular, the fact that a treaty has not entered into force between certain of the parties or that a difference has appeared between a State and a depositary with regard to the performance of the latter’s function shall not affect that obligation.”

- Article 77(1)(d) of the Vienna Convention, regarding the functions of the depositary, which requires:

“examining whether the signature or any instrument, notification or communication relating to the treaty is in due and proper form and, if need be, bringing the matter to the attention of the State in question.“

- Article 77(2):

“In the event of any difference appearing between a State and the depositary as to the performance of the latter’s functions, the depositary shall bring the question to the attention of the signatory States and the contracting States, or where appropriate, of the competent organ of the international organization concerned.”

- The 1999 Summary of Practice of the Secretary-General as Depositary of Multilateral Treaties (ST/LEG/7/Rev 1)3, prepared by the Treaty Section of the Office of Legal Affairs, analyses, on the basis of practice, those situations in which the Secretary General must ascertain whether a State or an organization may become a party to a treaty deposited with him. (Chapter V, Paragraph 73)

Such practice addresses various formulae for issuing depositary notifications in situations where a treaty is open to “all States” (as is the case of the ICC Statute), but where the applicant is not a member if the UN or party to the International Court of Justice. In such situation, paragraph 79 addresses the situation where:

“…. a difficulty has occurred as to possible participation in treaties when entities which appeared otherwise to be States could not be admitted to the United Nations, nor become parties to the Statute of the International court of Justice owing to opposition, for political reasons of a permanent member of the Security Council.”

The document goes on to state, in Section 80:

“…the Secretary General has on a number of occasions stated that there are certain areas in the world whose status is not clear. If he were to receive an instrument of accession from any such area, he would be in a position of considerable difficulty unless the Assembly gave him explicit directives on the areas coming within the “any State” or “all States” formula. He would not wish to determine, on his own initiative, the highly political and controversial question of whether or not the areas, whose status was unclear, were States. Such a determination, he believed, would fall outside his competence.

He therefore stated that when the “any State” or “all States” formula was adopted, he would be able to implement it only if the General Assembly provided him with the complete list of the States coming within the formula…..”

This practice of the Secretary General became fully established and was clearly set out in the understanding adopted by the General Assembly without objection at its 2202nd plenary meeting, on 14 December 1973, whereby “the Secretary-General, in discharging his functions as a depositary of a convention with an “all States” clause, and whenever advisable, will request the opinion of the Assembly before receiving a signature or an instrument of ratification or accession.”

Clearly, in light of the above, the “all States” formula as it appears in articles 125 and 126(2) of the ICC Statute, is intended to refer solely to established States and not to entities which, while claiming to be states, are not sovereign entities.

In this context, 2012 General Assembly resolution 67/90 which upgraded the Palestinian status within the UN to that of a “non-member observer state”4 and which is being cited by the Palestinian leadership as the authority for its requests for acceptance by the court, cannot be considered, by any legal interpretation or analysis, as indicative of, or granting statehood, nor as a legitimate source of guidance to the Secretary General in determining whether the Palestinian request for accession is “in due and proper form” as required by Article 77 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties.

That resolution did nothing more than to reaffirm in recommendatory form “the right of the Palestinian people to self-determination and to independence in their State of Palestine” and recommended that the various organs within the United Nations system “continue to support and assist the Palestinian people in the early realization of their right to self-determination, independence and freedom.”

That resolution did not establish or acknowledge Palestinian statehood or sovereignty as such, and did nothing more than to call for “the attainment of a peaceful settlement in the Middle East that ends the occupation that began in 1967 and fulfils the vision of two States: an independent, sovereign, democratic, contiguous and viable State of Palestine living side by side in peace and security with Israel on the basis of the pre-1967 borders“. The peace negotiation process and peaceful settlement envisaged was indeed referred to in the preamble to this resolution and is ongoing.

Clearly this resolution did not create a state of Palestine. A political General Assembly cannot and should not serve to guide the ICC Prosecutor in carrying out her legal functions. Clearly, the General Assembly is not a judicial body, but a political one. Its determinations are political, not legal.

By the same logic, the ICC Prosecutor’s most recent announcement, dated January 17, 2015, of her intention to open a “preliminary examination into the situation in Palestine” following a Palestinian declaration of acceptance of the court’s jurisdiction under article 12(3) of the ICC Statute, would appear to be similarly ultra vires. This in light of her determination that the Palestinian Authority is a state based solely on her reading of the above-noted General Assembly Palestinian upgrade resolution 67/90 which, as stated above, represents nothing more than the political position of the states voting in favor of it.

In view of the above, and taking into consideration the accepted international criteria for statehood as set out in the 1933 Montevideo Convention5 which include among other things, a unified territorial unit and responsible governance of its people, and capability of fulfilling international commitments and responsibilities, no serious UN organ or the Prosecutor of the ICC could, logically accept the Palestinian authority’s claim to statehood and accession to the ICC Statute, as well as to other international conventions limited to “States” or to “all States.”

In light of the above, and with a view to protecting the integrity of the ICC and honoring the basic purposes and principles for which it was established, and in order to prevent any further damage, you are requested to review your recent determinations and to reject the attempts to politicize the ICC.

Respectfully,

Alan Baker, Ambassador (ret’), Attorney,

[Signed]

Director, Institute for Contemporary Affairs

Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs

International Criminal Court Opens Inquiry into Possible War Crimes in Palestinian Territories

1 http://www.icc-cpi.int/NR/rdonlyres/EA9AEFF7-5752-4F84-BE94-0A655EB30E16/0/Rome_Statute_English.pdf

2 http://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/conventions/1_1_1969.pdf

3 https://treaties.un.org/doc/source/publications/practice/summary_english.pdf

4 A/Res/67/19, 26 November 2012, http://unispal.un.org/unispal.nsf/0080ef30efce525585256c38006eacae/181c72112f4d0e0685257ac500515c6c?OpenDocument

5 Article 1, 1933 Montevideo Convention, http://www.cfr.org/sovereignty/montevideo-convention-rights-duties-states/p15897

– See more at: http://jcpa.org/article/international-criminal-court-opens-inquiry-possible-war-crimes-palestinian-territories/#sthash.glo3yXF9.dpuf