Salim Fattal was just eleven when the two-day Baghdad pogrom known as the Farhuderupted on Shavuot (Pentecost) 74 years ago, yet its memory is engraved deep in his soul. Despite the passage of time, the shrieks and wails of the pogrom’s 179 Jewish victims still echo in his ears.

On 1 June, the first day of Shavuot in 1941, Fattal, his widowed mother and four siblings witnessed unimaginable terror, as he describes in his vivid memoir In the Alleys of Baghdad:

Helpless Jews had been cornered in their homes and fallen easy prey to robbers, murderers and rapists, who abused their victims to their heart’s content, with no let or hindrance. They slit throats, slashed off limbs, smashed skulls. They made no distinction between women, children and old people. In that gory scene, blind hatred of Jews and the joy of murder for its own sake reinforced each other.

Salim’s uncle Meir was pulled off a bus by a raging mob baying for Jewish blood, and never seen again.

Salim and his family managed to get through the night unscathed by bribing a local policeman to stand guard over their house. Haggling over how much he would be paid for each bullet he fired at the rioters, the policeman finally settled with the family at a quarter of a dinar for each shot.

The Farhud (meaning “violent dispossession”) marked an irrevocable break between Jews and Arabs in Iraq and paved the way for the dissolution of the 2,600-year-old Jewish community barely 10 years later. Loyal and productive citizens comprising a fifth of Baghdad, the Jews had not known anything like the Farhud in living memory. Before the victims’ blood was dry, army and police warned the Jews not to testify against the murderers and looters. Even the official report on the massacre was not published until 1958.

Despite their deep roots, the Jews understood that they would never, along with other minorities, be an integral part of an independent Iraq. Fear of a second Farhud was a major reason why 90 per cent of Iraq’s Jewish community fled to Israel after 1948.

But the Farhud was not just another anti-Jewish pogrom.The Nazi supporters who planned it had a more sinister objective: the round-up, deportation and extermination in desert camps of the Baghdadi Jews.

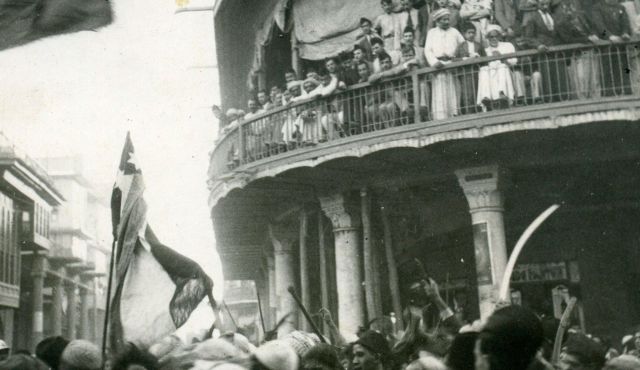

The inspiration behind the short-lived pro-Nazi government led by Rashid Ali al-Gaylani in May 1941, and the Farhud itself, came not from Baghdad, but Jerusalem. The Grand Mufti, Haj Amin al-Husseini, sought refuge in Iraq in 1939 with 400 Palestinian émigrés. Together, they whipped up local anti-Jewish feeling. An illiterate populace imbibed bigotry through Nazi radio propaganda. Days before the Farhudbroke out, the proto-Nazi youth movement, the Futuwwa, went around daubing Jewish homes with a red palm print. Yunis al-Sabawi, who, together with the Mufti and Rashid Ali, spent the rest of the war in Berlin broadcasting propaganda, instructed the Jews to stay in their homes so that they could more easily be rounded up.

The Farhud and the coup which preceded it, a failed attempt to spark a pro-Nazi insurgency, cemented a wartime Arab-Nazi alliance designed to rid Palestine, and the world, of the Jews. The Mufti had secret plans to build crematoria near Nablus.

The Mufti’s postwar legacy endured. Six months after the end of WWll, and before Israel was established, vicious riots broke out in Egypt and Libya – the latter, incited by anti-Jewish hatred, claimed more than 130 lives. Barely three years after the full horror of the Holocaust had come to light, Arab League member states embarked on a programme of ethnic cleansing Hitler would have been proud of. The uprooting of the 140,000 Jews of Iraq followed a Nazi pattern of victimisation – dismantlement, dispossession and expulsion. Nuremberg-style laws criminalised Zionism, freezing Jewish bank accounts, instituting quotas and restrictions on jobs and movement. Every Arab state adopted all, or some, of these anti-Jewish measures. The result was the exodus of nearly a million Jews from the Arab world.

While the world has devoted all its attention to the Palestinian “Nakba,” until recently, Israel has said and done little to publicise the monumental injustice done to the 870,000 Jews driven from Arab countries.

More Jews died than on Kristallnacht, yet the Farhud has not become part of Holocaust memory. Indeed, the Washington Holocaust Museum had to be vigorously lobbied to include the Farhud as a Holocaust event.

Since that fateful event, so effectively has history been distorted that even Jews believe that Arabs had no part to play in Nazism. A body of opinion mainly on the Left has turned the facts on their head and is convinced that the Palestinians paid the price of the Holocaust, and that Israelis are the new Nazis.

Yet Nazism was popular in the Arab world – and not just because the Germans were fighting the British and French colonial powers. Nazism gave ideological inspiration both to Arab secular nationalist parties and the Muslim Brotherhood (Gaza branch: Hamas). Antisemitism – a synthesis of Nazi tropes and traditional Koranic prejudice – is at the core of Islamist beliefs. Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the head of Islamic State (ISIL), was a member of the Muslim Brotherhood.

The Arab world’s most famous pro-Nazi, the Mufti of Jerusalem, should have been tried as a war criminal at Nuremberg. The unremitting campaign to destroy Israel through war, terror or political delegitimisation, is a manifestation of the unfulfilled genocidal intentions of Arab nationalism and Islamism.

The demons awakened by the Farhud are still with us today.

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/lyn-julius/demons-of-the-farhud-are-_b_7427494.html