Failure is often followed by clarity, and beginning Tuesday night, I’ll have an opportunity to think about just how cathartic changing your routine can be.

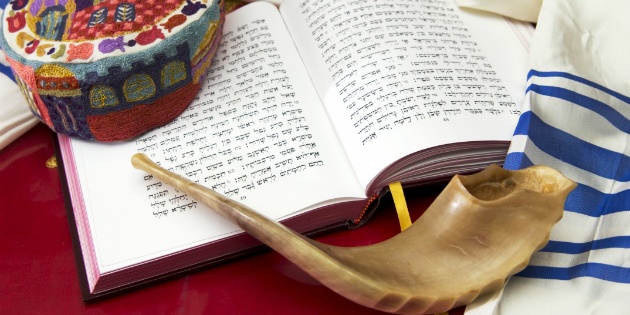

Yom Kippur is not for rookies, and if you take the liturgy literally, it can be a major bummer. Observant Jews believe it is the day that God judges who will live and who will die. During five services — stretching over a 25-hour period — we will remember the dead in a memorial prayer, read about rabbis who were tortured because of their brilliant scholarship, and beg for our lives numerous times. All the while abstaining from eating and drinking and just about everything else that’s part of our daily routine.

On the surface, there’s little joy to the holiday, especially around breakfast time Wednesday morning, some 12 hours after your last meal. Instead of coffee and the morning paper, there’s prayer awaiting, hours and hours of it. I used to dread this, even as a child when I didn’t fast. In recent years, though, I’ve decided that the fast is the most appealing part of the holiday.

Since I was in my late teens, I’ve been able to complete the fast almost every year, but I use common sense: If I feel faint or sick, the fast is over.

As the day progresses, the pageantry and mournful melodies form a portal for those who fast. Where do you go while abstaining from food and drink for a day? I travel to the past and future, holding a prayer book.

When the memorial prayer for the dead is chanted, I am a child again, walking with my father to shul on this holiday. We’re dressed in suits; he carries his prayer shawl in a velvet bag and smokes a Salem as we stroll. Every other day, he is a deli man — headed off to work slicing meat and serving up huge corned beef and pastrami sandwiches to the working class of the 1960s and ’70s.

Today, though, he is regal. His suit fits perfectly; his gait is that of a philosopher. His words are few and he smiles for the entire walk. When we reach the shul, it is packed with congregants, and our seats are on a stage at the end of the sanctuary. I ask him why we don’t sit closer and he shrugs. “We’re here. That’s what matters,” he tells me.

There are no assigned seats at the synagogue I now attend, and people are free to roam as they like. Sometimes, I stand next to the ark, which holds the Torahs. But now, I feel most comfortable in the balcony. There I can view the entire congregation and feel the wave of song, which grows more authentic as the day progresses.

I close my eyes, and I can see Ben, a friend whose presence and words unfold like a prayer. A trained rabbi, psychotherapist, and attorney, he seems to have the answer to every question. He has been dead for four years now, but when I find my way to our place up in the balcony, I open the window because I know he liked fresh air. I hear his raspy voice lost between the melodies. His seat is empty, but is he not with me?

Morning and early afternoon move slowly. With all of this talk of living and dying, I wonder how many more years I will live. A collage of happiness washes over me, and clips as from a filmstrip play: I am 20, swimming in the Red Sea by the Sinai and thinking about world peace; I am 33, it’s the end of the Yom Kippur fast, and I propose to Devorah; two years later, Aaron is born, and he joins me each holiday at the shul. This year he is in college in London. What is he doing today?

On this day of atonement, the rabbi usually talks about never giving up. I embrace this as a central theme to the holiday, that perfection can emerge from repeated failure; that action, not just thought, is required to complete something that you really want; that the process is just as important as the outcome.

As the fast nears its end, and the congregation joins in a final plea to be included in the book of life, I await the blast of the shofar, the ram’s horn that is sounded at the end of the holiday. It pierces the air like no other instrument and I try to grab hold of the notes as they float toward the heavens.

Soon, I eat and talk about the same old things. Does the holiday have any lasting impact on my life, or is it just ritual? I may never know.

http://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/regionals/north/2015/09/19/yom-kippur-day-when-time-stands-still/agKOr9S4eQpN0CW8KzBgNM/story.html