Chapter 1: The Jewish People’s Right and Birthright in Jerusalem

(the Historical-Religious Dispute)1

The nature of this opening chapter, which focuses on the historical-religious dimension, may seem to run counter to the practical emphasis of this study, which analyzes the dangers of dividing Jerusalem on a practical level. Nevertheless, this chapter is essential. For the Jewish people, Jerusalem is not just matter but also spirit, heritage, and memory, as well as a unifying factor and one of the basic principles of the Jewish people’s identity. There is no point in analyzing the liabilities and many perils of division without first clarifying the historical and religious heritage of Jerusalem for the Jewish people, their profound bond with it and birthright attached to it. It is useless to explain how division will endanger our security without shedding light on our attachment to this specific city, since security can perhaps be attained elsewhere. Omitting this fundament is like putting someone on a nutritious diet, so that he will improve his health rather than jeopardize it, without this person grasping the purpose of his existence. The question of “Why does one exist?” or “Why Jerusalem?” must be asked before one deals with the practical nuts and bolts.

As fate would have it, this book is being rewritten while a kind of intifada rages in Jerusalem. The battle over the physical land of Jerusalem is being fought in tandem with a battle over history and truth. The phenomenon of de-Judaization of the Temple Mount, the Western Wall, and Jerusalem in general – as pursued by many in the Muslim world and among the Palestinian population – is occurring simultaneously with attacks, sometimes murderous, on Jews and on Israeli targets. The renewed writing and rewriting of Muslim history in the Land of Israel and Jerusalem run parallel to ongoing riots and violence against Jews on the Temple Mount.

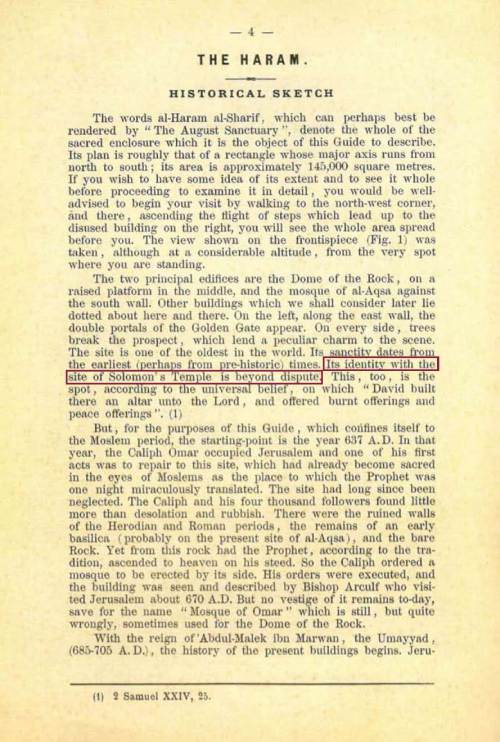

The frequent proclamations of the “Sheikh of Al-Aqsa,” Raed Salah, head of the northern branch of the Israeli Islamic Movement, who on many occasions denies any Jewish connection with Jerusalem and the Temple Mount,2 are no longer unusual. Mahmoud Abbas’s religious-affairs adviser, Mahmoud al-Habash, asserted only recently that “Jewish Jerusalem is a legend;” former Palestinian Prime Minister Abu Ala declared that the gold medallion recently discovered in an archeological dig at the Southern Wall of the Temple Mount, notable for its classic Jewish symbols such as a menorah, a shofar, and a Torah scroll, is just a forgery; Adnan al-Husseini, the Palestinian Authority’s (PA) minister for Jerusalem affairs, stated that “Israel has a policy of ‘Judaization’ and ‘fabrication’ whose aim is to invent a Jewish connection with Jerusalem.” Salah, al-Habash, Abu Ala, and al-Husseini have numerous confederates in the Muslim world and the PA,3 who voice hundreds and thousands of similar falsehoods.4 Already a decade ago, in May 2014, Dr. Yitzhak Reiter noted in his book From Jerusalem to Mecca and Back5 that “during the most recent generation the Arab Islamic history of Jerusalem is being rewritten.” Muslims are now revising the history they had accepted for years, as documented in their writings. The central claim concerns the age and status of the Al-Aqsa Mosque; this mosque and its history are fundamental to Muslim identity in Jerusalem.6 Thus it is now asserted that the mosque, which was built about 1,400 years ago, dates back to the pre-Islamic period, even before the existence of the Temple. The Muslims have altered the time scheme that was documented in their own books and upheld by them; they have begun to say that they actually ruled Jerusalem thousands of years before the Jews did.

Reiter’s research examined religious rulings by major muftis in the Muslim world, websites of Islamic movements, and many popular works in Arabic dealing with Jerusalem. He described, on the one hand, the dismissal of the Jewish narrative and of any Jewish connection with the city, and on the other, the exaltation of Jerusalem’s status in Islam. Today’s demand to make the city the capital of the Palestinian state has spawned a new bevy of lies and fabrications.

The new Muslim narrative about the Al-Aqsa Mosque avows, for example, that it was built by the first man. Jordanian Waqf Minister Abdel Salaam al-Abadi had already made this claim in 1995. The Saudi historian Muhammad Sharab also states that Al-Aqsa was built by the first man, and the former mufti of Jerusalem and the PA, Sheikh Akrama Sabri, says the same. In recent years spokesmen of the southern branch of the Islamic Movement have declared that it was the Patriarch Abraham who built Al-Aqsa 4,000 years ago, 40 years after he built the Kaaba in Mecca with his son Ishmael.7 In order to Islamize the period before Muhammad’s prophecy, previous Muslim traditions were invoked that had been of negligible importance. Further layers have been added to the Al-Aqsa story, more ancient ones, going back much earlier than the year of its construction, and earlier of course than the presence of the Israelites in the Land of Israel.8

The Koran verse that mentions the “farthest” mosque, and goes on to say “whose precincts we did bless,” has also won an expansive interpretation. The “precincts” of Al-Aqsa are no longer defined in limited fashion, as in the past; in the new interpretation they refer to all of Jerusalem and even all of Palestine.

The new history, which is most infuriating, treats the Temple – which is documented in the Bible, the Mishnah, the Gemara, and other historical sources – as a lie that was invented by the Jews. In recent years, when referring to the Jewish Temple, the Arab public discourse regularly adds the words “al miza’um,” meaning “supposed” or “fabricated.” Sheikh Ekrima Sabri, for example, the former mufti of Jerusalem, said on several occasions that there exists no relic that proves the Jews’ claim that there was a Temple at the spot.9 One of his predecessors, Sheikh Saad al-Din al-Almi, who was mufti of Jerusalem in the 1980s, averred at the time that the Jews contaminate the Muslimness of Jerusalem.10 Since then, of course, many others have made similar statements – including, during the “Jerusalem Intifada,” Mahmoud Abbas himself.

One day over a decade ago I came with a group of archeology students from Bar-Ilan University to the banks of the Kidron Valley in Jerusalem. The group wanted to salvage archeological relics from the heaps of earth that the waqf [Muslim council] had excavated on the Temple Mount and then hauled in trucks to the riverbed. A waqf member who discerned the students broke out in loud shouts at them. One sentence registered well among them: “You have nothing to look for here, just as the Crusaders had nothing to look for here! Jerusalem is Muslim!”11

If in the past such an incident may have been odd and marginal, since the 2000 Camp David Summit that is no longer the case. Not only has the claim that the Jews have no real connection with Jerusalem and the holy places been widely inculcated in the Arab and Muslim communities and become prominent in the Arab public discourse, but the Palestinian leadership – and not only Yasser Arafat – have adopted it as well.

Long after completing his tenure as foreign minister in the government of Prime Minister Ehud Barak, the historian Shlomo Ben Ami wrote:

In August and September 2000, the Temple Mount was no longer under Israeli sovereignty and Palestinian trusteeship, but completely under Palestinian sovereignty. All we asked for was sovereignty over the earth under the mount, but the Palestinians completely disdained our request. They said again and again that there was nothing there, and never had been anything there. They denied that we have any right to the Temple Mount.12

Yossi Alpher, a former senior Mossad official, who was director of the Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies at Tel Aviv University, observed even more pointedly:

Out of all the statements about the peace process made by Yasser Arafat and his associates in the months from Camp David (July 2000) to Taba (January 2001), none was as offensive and objectionable as the one that there was never a Temple on the Temple Mount. Indeed, Arafat discounted the fundamental Jewish belief that the Land of Israel is the historical homeland of the Jewish people. Like most of the Jews, religious and secular, I saw these words as an attempt to find fault with our national identity.13

From denying the Jewish connection with the Temple Mount, it was a short path to denying the Jewish connection with the Western Wall and with Jerusalem as well. In recent years the Palestinians have intensified the Islamization of the Western Wall; among other things, PA spokesmen now claim Palestinian sovereignty over the wall as well.14 Muslim spokesmen have also appropriated the wall exclusively to Islam. The Al-Aqsa Institute for the Sacred Endowment and Muslim Heritage proclaimed that the Al-Buraq Wall (the Western Wall) is “exclusively a Muslim sacred trust…and non-Muslims have no right to this wall.”15 The abovementioned Sheikh Sabri stated that “the Western Wall belongs only to Muslims.”16 And Nasser Farid Wasal, the mufti of Egypt, explained that “the Western Wall is a Muslim sacred endowment and part of the western wall of the Al-Aqsa Mosque, and Muslims are forbidden to relinquish it, or to engage in renovating it.”17

Such assertions would not be worth refuting were it not for the fact that the Palestinians use them to claim exclusivity in the heart of the Jerusalem – the Temple Mount, its walls, the Old City, and the surrounding area – and were these notions not becoming so widespread in the Arab and Palestinian street.18

* * *

It is clear that since 1967, the Israeli claim to Jerusalem has not only been based on practical considerations but, primarily, on a deep commitment to the Jewish right and connection with Jerusalem, or what was called over the years the “dream of Jerusalem.” The roots of this “dream” lie deep in the Jewish past.

The Temple Mount is not just a mount but, rather, the “home of God.” A permanent temple to the God of Israel stood there, the extension of the “Tabernacle” – the place where the shekhinah dwelled during the Israelites’ wanderings in the desert.19 According to the Book of Chronicles, it was King David who broke the ground for the building of the Temple.20 The Bible tells how David bought this piece of land from Araunah the Jebusite for 50 shekels.21 King Solomon, David’s son, built the Temple on the plot of land that was purchased from Araunah’s threshing floor – that is, on Mount Moriah.22 According to the Aggadah, the first man was created from the earth of this mount,23 and at the end of the Flood, while the waters were drying up from the earth, Noah built an altar to God there.24 It was here that God tested Abraham, and the Binding of Isaac transpired.25 The Mishnah in Tractate Middoth details the measurements of the Temple Mount. Tractate Keilim sets forth ten ascending degrees of holiness in the Land of Israel, Jerusalem, and at the Temple itself.26 For generations Jews longed for Jerusalem and the Temple, expressing their yearning in piyyutim (liturgical poems) and prayers. The Temple was the center of the Jewish people’s spiritual life, and its main role was to suffuse them with the shekhinah.27

The destruction of the two Temples – the first by Nebuchadnezzer (586 BCE) and the second by the Romans (70 CE) – altered the reality in Jerusalem and the Land of Israel, but also fostered generations of dreamers and poets who prayed and yearned for Jerusalem and the Temple. The poet Avigdor Hameiri, for example, wrote of those thousands of generations of dreamers and saw Jerusalem as a “royal city.” In 1966 the writer Shai Agnon, in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, said that, while he had been born in one of the towns of the Exile because of a historical catastrophe (the destruction of Jerusalem), he had always regarded himself as having been born in Jerusalem. “Hatikvah,” the national anthem of Israel, ends with the words: “To be a free people in our land, the land of Zion and Jerusalem.” The author of “Hatikvah,” Naftali Herz Imber, expressed the longing of generations for Jerusalem and in the poem’s nine verses mentioned its name eight times.

![Inscribed on the stone: “To the Trumpeting Place to [Announce the Shabbat].” The stone was found amid a rockslide at the foot of the southwestern wall of the Temple Mount. The finding validates the historical sources (the Sages and Josephus) that describe the High Priest in Second Temple days announcing the arrival and departure of Shabbat with a series of trumpet blasts. (Israel Antiquities Authority; photograph from the Israel Museum, Jerusalem)](http://israelbehindthenews.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/stone.jpg)

The holiness of Jerusalem is linked to the Temple, which is on the Temple Mount, the location of the shekhinah. Rabbi Yochanan ben Zakkai, who was smuggled out of Jerusalem in a burial coffin during the Roman siege in 70 CE and founded the spiritual center at Yavneh, may have assumed that the Jews would no longer need the earthly Jerusalem and instead would suffice with the Torah of Moses and of God, its giver. He was proved wrong. After the destruction of the Temple, Jerusalem’s holiness only intensified; it was Jerusalem as a focal point that preserved the unity and uniqueness of an exiled, dispersed people. The commemoration of the destruction became an annual tradition, in which hope was also expressed for the future. For two thousand years the prayers and dreams of Jews centered on the rebuilding of Jerusalem and the Temple. All over the world Jews prayed that “he will build the Temple speedily in our days.” The phrase “Next year in a rebuilt Jerusalem” became the flag and the anthem that bound together the Diaspora communities throughout the Exile – including the founders of Zionism, the Jewish national liberation movement.

The holiness of the city and the memory of its glory are entwined with almost every holiday and religious ceremony that Jews practice in the Diaspora – morning, noon, and night (Shacharit, Mincha, and Arvit). This not only pertains to a funeral, a circumcision, a bar mitzvah, or to the blessing of the food (Birkat Hamazon) at the end of a meal, but even to a wedding. When the two members of a couple recite the marriage vows, Jerusalem is integral to the building of the new family: “If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, may my right hand lose its cunning,” says the groom; “Let my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth, if I set not Jerusalem above my chiefest joy.” Jerusalem is always present, carrying a huge emotional charge. It is never forgotten. Even after the destruction, even under the most difficult and dangerous conditions, pilgrimage to the city did not stop:

Just as a dove, even though you take her chicks from under her, does not desert her dovecote, so with Israel, for despite the destruction of the Temple, the three pilgrimage festivals were not annulled. (Shir Hashirim Rabbah 4:28)

After the Bar Kochba Revolt, Jews were allowed, on Tisha B’Av, to enter the city and lament the destruction in return for a large sum of money. During the Muslim conquest, Jews of all the Diaspora communities would go to Jerusalem for the Sukkot holiday and pray on Hoshanah Rabbah on the Mount of Olives, which overlooks the Temple Mount. In 1322, Ishtori Haparchi in his book Kaftor Vaferech wrote that the Jews of Damascus and Egypt would go to Jerusalem on holidays and memorial days. Throughout all the generations Jews ascended to Jerusalem to pray there, kiss its soil, and also to die there and be buried on the Mount of Olives.

Judaism designated three fast days in memory of the Temple: the Tenth of Tevet – the day on which the Babylonian siege of Jerusalem began; the Seventeenth of Tammuz – on which the walls of Jerusalem were breached by the Romans; and Tisha B’Av – the day of the destruction of Jerusalem and the razing of the Temple. Seventy years after the downfall of the First Temple, the building of the Second Temple began, and continued for eighteen years. In the year 70 CE, the Romans burned it down. Throughout the long Exile, however, Jews never ceased – even if few in number – to live in Jerusalem.

Up until the Islamic conquest, the city was ruled successively by Jews, Egyptians, Greeks, Persians, Parthians, Romans, and Byzantines. Islam, which now claims priority and precedence over Jerusalem and its holy places, only emerged two thousand years after the Jews became a people. The Palestinians, who claim east Jerusalem – including the Old City and the Temple Mount – as their capital, only began to define themselves as a people about a hundred years ago. After the conquest of Canaan in the 13th century BCE, the Jews ruled the Land of Israel for a thousand years, and they have lived there continuously over the past 3,300 years. During that epoch Jerusalem has been the Jewish capital, while it has never been a capital city, either in the ideological or political sense, of any Arab or Islamic political entity. The ostensible “forefathers” of the Palestinians – Muslims, Arabs, Mamlukes, and Ottomans who dwelled in the Land of Israel – never applied national sovereignty to the Land of Israel as a distinct geographic entity. They conquered it and governed it, but their political hub was always someplace outside of it. Not even the Jordanians, when they controlled Jerusalem, made it their capital.

Jerusalem and Zion are mentioned 821 times in the Bible and another 3,212 times in the rabbinical literature.28 The Koran does not mention it even once. The Muslim holy city of Mecca, however, is mentioned hundreds of times in the Koran, and so is the city of Medina.29 When the Romans ruled Jerusalem, the city was called Iudaea. The name Al-Quds, which is what the Muslims call Jerusalem, comes from the Arabic words for “holy city”; the Bible refers to Jerusalem as the “holy city” 37 times. Until the 10th century CE, the Muslims called Jerusalem Aeolia, as the Christians did, and used this name on their coins. It was in the ninth century that the Muslims first called Jerusalem Beit al-Maqdis, which was derived from the Aramaic Karta Dakudsha, and only in the 11th century was it called Al-Quds. The Muslims also called Jerusalem “Tzahion,” based on the biblical name Zion.30

The Dome of the Rock and the Al-Aqsa Mosque, which have been the sacred Muslim edifices on the Temple Mount for about 1,400 years, were built to commemorate the triumph of Islam over the existing religions and to compete in glory with the magnificent Christian churches. Among other factors, the building of Al-Aqsa and the Dome of the Rock resulted from Muslim internecine wars, without any special sacredness being assigned to Jerusalem. The dome, as Prof. Menashe Harel once noted, is covered with about 240 meters of verses, but not even one of them mentions Jerusalem. Mecca, which is in the midst of the Arabian Desert, is the holy city of the Muslims.

In the Koran, Jerusalem is not mentioned at all except in an interpretational allusion that occurs in the first verse of Sura 17. Ancient Muslim commentary did not identify Al-Aqsa (which means “the extremity,” “the farthest”), from which Muhammad ascended to heaven, with the Temple Mount in Jerusalem but with the Heavenly Temple – which, in Muhammad’s days, was in no way a mosque on the Temple Mount. Jerusalem was not part of the world of Muhammad and the ancient Muslims; the focus was solely on the Arabian Peninsula.31

Up to the year 622, when praying, the idol-worshipping residents of Medina would turn toward the Kaaba in Mecca; the Jews would turn north toward Jerusalem. During a short period of sixteen months, Muhammad ordered his believers to turn in their prayers toward Jerusalem; he thereby hoped to convince the Jewish tribes in Mecca to convert to Islam. When he realized he had failed, the Qibla (direction of prayer) was determined to be toward the Kaaba in Mecca. The term for Jerusalem in Muslim tradition, however, remained “the first Qibla.”32

The Muslims’ basic attitude toward Jerusalem as the capital of Israel is the same as their basic attitude toward Israel in general. In the doctrine of the Prophet Muhammad, the Jews came to represent a people cursed by God; they were portrayed as the ones who had distorted his revelations. The Jews were indeed tolerated in the Muslim world, but only as an inferior people without political rights, including the right to take part in political life.

As Prof. Moshe Sharon, a Middle East scholar, has observed:

In the eyes of Islam, the establishment of the state of Israel violated all the rules concerning Islamic territory, Islamic holy places, and the legal status of Jews according to Islam. The state of Israel was established on an area that belongs to Dar al-Islam, on which Islamic holy places exist. The Jews are not lowly as they are destined to be, and gravest of all is that they rule Muslims; this situation is not at all tolerable.33

Dozens of fatwas issued by Muslim clerics since 1967 describe the Jews as enemies of the believers and as contaminating the Islamic nature of Jerusalem. This easily led, of course, to historical fabrications and the rewriting of history to convince the Arab and Muslim word that Jerusalem belongs to them throughout the generations, while the Jews are no more than guests and invaders there.

In contrast to the Jewish attachment and continuity in Jerusalem, in the past the city played almost no role in the political and cultural life of the Arabs. Damascus, Baghdad, and Cairo certainly did. Jerusalem did not. Ramle, for example, the only town in the country that was founded by Muslims (in the first Arab conquest), became the capital of a district; Jerusalem did not. Even under Muslim rule there was a Christian majority in Jerusalem for long periods, and over the years the city never – with the exception of the Jews – became the capital of any nation. It was only when Jerusalem fell into the hands of non-Muslim rulers, whether Christian Crusaders at the beginning of the previous millennium or Jews at the end of that millennium, that the Muslims suddenly elevated Jerusalem from a religious symbol, secondary in importance, to a national-religious symbol of the first order. Muslims leaders seized on Crusader rule in the city to glorify Jerusalem in the Muslim word, and they did the same when the Jewish people returned to Jerusalem. Suddenly the city, whose status during Jordanian rule had been eroded by the Jordanian monarchy, underwent a quantum leap in sanctity and political importance. Poems of yearning for Muslim Jerusalem now appeared in the Arab world, and almost every self-respecting Arab ruler set up special committees on the issue of Jerusalem and the Temple Mount.

Since June 1967, the religious weight of Jerusalem and of Al-Haram al-Sharif (the Temple Mount) has constantly increased in the Muslim world. Despite its being in the third place in religious importance, its emotional, political, and religious valence has risen, particularly because of Israel’s rule of the city and its holy places.34 The familiar “Al-Aqsa is in danger” campaign,35 which the Muslims have already waged for a hundred years, and all the more since the Six-Day War, is not one of our concerns here but well serves this tendency.

* * *

The Zionist movement began to fulfill the “dream of Jerusalem” with Israel’s establishment in 1948, and even more with the liberation of Jerusalem, the Old City, and the Temple Mount in 1967. In the name of this “dream,” for 33 years36 various declarations of allegiance were made to a complete and united Jerusalem under Israeli sovereignty.

One cannot base one’s claims regarding the Jerusalem issue on existential-security needs alone. These claims must be based, as most Israeli governments and Zionist leaders have done since 1967, on a right – the Jewish people’s connection and commitment to Jerusalem. Such a commitment is not the same as the concern, important in itself, about ensuring physical existence. It rests mainly on the Jewish religion, tradition, culture, and history, which nurtured Jewish national awareness throughout the generations. Without this ancient legacy, what justification is there for the Jewish state’s existence in the Land of Israel, in particular, or for making Jerusalem the capital of the Jewish people and their state?

When David Ben-Gurion, during the 1948 War of Independence, had to fight for Jerusalem and coordinate the struggle over it, he said:

The value of Jerusalem cannot be measured and weighed and counted. If a land has a soul, then Jerusalem is the soul of the Land of Israel, and the battle over Jerusalem is determinative and not only from a military standpoint….Jerusalem demands and deserves that we stand with her. The pledge of “By the waters of Babylon” obligates us today as it did in those days. Otherwise we will not be worthy of the name of the Jewish people.37

A powerful, poetic expression of the link between the Jewish people and Jerusalem was given by my grandfather, Shlomo Zalman Shragai, the first elected mayor of Jerusalem after the establishment of the state, in a speech he gave to thousands of representatives at the Church of Scotland in Edinburgh in 1947:

The connection between us and Jerusalem is like the connection between an only son and his mother. This is our city, city of the monarchy and the Temple – exclusively ours, and we are its exclusive people….Jerusalem went behind us in the desert in an unsown land, and did not build itself by foreigners who came to its gates….All the while mother Jerusalem waited for her real sons…that they should return to her and renew her youth as capital of the Jewish state….For us there exists one and only capital: Jerusalem the Holy City.

Thus, the professional and practical analysis provided in this book does not exist in isolation from a worldview and a purpose. That analysis can, however, stand on its own and also inform those who feel detached from the world of tradition and values on which the Jewish connection with Jerusalem is founded.

* * *

Notes

1 This chapter is based on several principal sources: Yitzhak Reiter, M’Yerushalayim l’Meka v’Chazara: Hahitlakdut Hamuslimit saviv Yerushalayim (From Jerusalem to Mecca and Back: The Muslim Unification around Jerusalem) (Jerusalem: Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies, 2005); Nadav Shragai, Yerushalayim Eina Habaya Eile Hapitaron (Jerusalem Is Not the Problem but the Solution), in Moshe Amirav, ed., Adoni Rosh Hamemshala: Yerushalayim! (Mr. Prime Minister: Jerusalem!) (Jerusalem: Hotza’at Carmel and Florsheimer Institute for Policy Studies, 2005); Menashe Harel, Shalosh Hadatot v’Trumatan l’Yerushalayim v’Eretz Yisrael (The Three Religions and Their Contribution to Jerusalem and the Land of Israel) (Shaarei Tikva: Ariel Center for Policy Research, 2005); Shmuel Berkovitz, Milchamot Hamekomot Hakedushim (Wars of the Holy Places) (Jerusalem: Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies and Hed Artzi, 2000), 109-113. On the Muslims’ transferring, in recent centuries, of the sanctity of the Western Wall to the different walls of the Temple Mount, see Nadav Shragai, Hamaavak al Har Habayit: Yehudim v’Muslimim – Dat v’Politika (The Struggle over the Temple Mount: Jews and Muslims – Religion and Politics) (Jerusalem: Keter, 1995); Nadav Shragai, Alilat “Al-Aqsa b’Sakana”: Diukano shel Sheker (The “Al-Aqsa Is in Danger” Libel: The History of a Lie) (Jerusalem: Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs and Hotza’at Maariv, 2012).

2 Yoav Stern, Lo Hitbat’ut Yotze Dofen (“Not an Unusual Statement”), Haaretz, February 18, 2007, Omedia website. Ran Parchi cites statements in this vein by Salah; Member of Knesset Ibrahim Sarsur, chairman of the Ram-Tal Party; and by the mufti of Jerusalem, Akram Sabri.

3 See, e.g., examples at the Palestinian Media Watch website (Hebrew): http://palwatch.org.il/main.aspx?fi=605.

4 For more, see many categories at Palestinian Media Watch over the years.

5 See my summary in Nadav Shragai, Bereshit Haya Al-Aqsa: Shlomo b’Sach Hakol Bana Sham Chadar Tefila Katan (In the Beginning There Was Al-Aqsa: Solomon Just Built a Small Prayer Room There), Haaretz, November 27, 2005.

6 Reiter, M’Yerushalayim l’Meka, 21-23.

7 Ibid., 19.

8 Ibid. For more, see Shragai, Alilat “Al-Aqsa b’Sakana,” ch. 4, “Hamuslimim Meshachtevim et Hahistoria shel Yerushalayim” (The Muslims Are Rewriting the History of Jerusalem).

9 See Reiter, M’Yerushalayim l’Meka.

10 I was told this in an unofficial meeting with him during the years I worked as a journalist for Haaretz.

11 I also recounted this incident in my book Alilat “Al-Aqsa b’Sakana,” and in a lecture about Jerusalem that I gave in Paris in 2011.

12 Shragai, in Amirav, Adoni Rosh Hamemshala, 31.

13 For the full quotation and its source, see Shragai, Alilat “Al-Aqsa b’Sakana,” 56-57.

14 Reiter, M’Yerushalayim l’Meka, 42-43; see also reports in the Israeli daily media from October 11 and 12, 2007. For example, at Maariv’s website, Itamar Inbari, “Adnan Husseini, Yoetzo shel Abu Mazen: ‘Dorshim Ribonut al Hakotel’” (Adnan Husseini, Adviser to Abu Mazen: “We Must Have Sovereignty over the Western Wall”).

15 Dalit Halevi, “Hatnu’a Ha’islamit: Hakotel Shaiyach Rak Lamuslimim” (The Islamic Movement: The Western Wall Belongs Solely to the Muslims), website of Arutz Sheva, June 28, 2012.

16 Al Hayat al-Jadida, June 23, 2009.

17 Ynet, February 22, 2001.

18 Reiter, in M’Yerushalayim l’Meka, 9, notes that this is not a random sample of opinions; instead “they represent the main discourse in the contemporary Muslim world.”

19 Exodus 25-27.

20 1 Chronicles 28:11-12, 19.

21 2 Samuel 24.

22 2 Chronicles 3:1.

23 Bereshit Rabbah, Chapter 14:8.

24 Bereshit Rabbah, Chapter 34:1-2.

25 Bereshit Rabbah, Chapter 22:1-2.

26 Keilim, Chapter 1:6-9.

27 Exodus 25:8: “And let them make me a sanctuary; that I may dwell among them.”

28 Harel, Shalosh Dadatot, 13-14.

29 Shragai, in Amirav, Adoni Rosh Hamemshala, 21-33.

30 Harel, Shalosh Dadatot, 13-14.

31 There are views in Islam according to which monotheism is Islam before the Prophet Muhammad, and in this ancient Islamic era Al-Aqsa was built as a compound of walls and not as the edifice of a mosque. The edifice was added later. These views were dormant, not generally accepted, and not widespread. In our time they were rejuvenated, for reasons that this book will address.

32 Nadav Shragai, Har Hamerivah (The Temple Mount Conflict) (Jerusalem: Keter, 1995), 264; Emmanuel Sivan, Mitosim Politi’im Aravi’im (Arab Political Myths) (Tel Aviv: Sifriat Ofakim and Am Oved, 1988), 89-90; Chava Lazarus-Yaffe, “Kedushat Yerushalayim b’Masoret Ha’islam” (The Sanctity of Jerusalem in the Tradition of Islam), in Eli Shaltiel, ed., Prakim b’Toldot Yerushalayim Bazman Hehadash (Chapters in the History of Jerusalem in Modern Times), memorial volume for Yaakov Herzog (Jerusalem: Yad Ben Zvi and Misrad Habitachon, 1981).

33 Nativ, March 1992 (Hebrew).

34 For more, see Yitzhak Reiter, “Hashlishi b’Kedusha. Harishon b’Politika. Al Haram al-Sharif b’Eini Hamuslimim” (The Third in Holiness. The First in Politics. Al-Haram al-Sharif in the Eyes of the Muslims), in Ribonut Ha’el v’Ha’adam: Kedusha v’Merkaziut Politit b’Har Habayit (The Sovereignty of God and of Man: Sanctity and Political Centrality on the Temple Mount) (Jerusalem: Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies and Teddy Kollek Center for Policy Studies, 2001), 155-175.

35 For elaboration, see Shragai, Alilat “Al-Aqsa b’Sakana.”

36 Until Prime Minister Ehud Barak’s government agreed at the 2000 Camp David Summit to a division of Jerusalem and the Temple Mount.

37 David Ben-Gurion, b’Hilachem Yisrael (Fighting for Israel) (Tel Aviv: Am Oved, 1975), 90-91.

– See more at: http://jcpa.org/jewish-peoples-right-jerusalem/#sthash.u1yJDNbF.dpuf

Chapter 1: The Jewish People’s Right and Birthright in Jerusalem (the Historical-Religious Dispute)