A few weeks ago, the Trump Administration announced it would end all US funding for UNRWA, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency, established in December 1949 to support Palestinian refugees. In recent years, that funding has totaled some $350 million annually.

A few days later, Senator James Lankford, a Republican from Oklahoma, introduced a bill to withhold aid until UNRWA changed its definition of “Palestinian refugee.” The definition currently encompasses those who became refugees in 1948 and 1967, as well as their offspring, no matter how many generations down the line – a policy at odds with every other international organization working with refugees.

“It’s absurd,” Likud legislator Sharren Haskel, who heads the Knesset caucus seeking UNRWA reforms, told the Jewish Journal.

“When you look at Gaza, which has autonomy, or Ramallah, which has autonomy, they have refugee camps for their own people,” she said. “The Palestinians are basically perpetuating the Israeli-Palestinian conflict by raising the fifth and sixth generations of refugees.”

There’s wide agreement that UNRWA has been one of the main forces facilitating this continuity. Seen by many as a runaway UN agency, its schools use Palestinian Authority textbooks that have been shown to glorify armed struggle, and it is believed that thousands of its teachers belong to terrorist organizations.

For more than a decade, its teachers’ union has been run by Hamas strongmen such as Suhail al-Hindi, a former UNRWA school principal who is now a member of Hamas’ senior leadership. Other UNRWA educators have included Said Sayyam, a former Hamas interior minister and civil affairs minister who taught in UNRWA schools for 23 years, and Awad al-Qiq, ex-headmaster of an UNRWA school who led an Islamic Jihad engineering unit that built bombs and Qassam rockets.

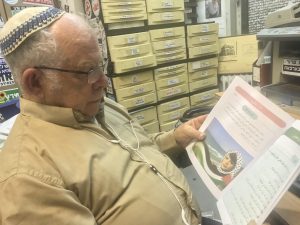

The Knesset caucus on UNRWA has been in existence for around a year and a half, but David Bedein has been seeking to throw a wrench into the works of UNRWA for some three decades. Many believe it’s his work, which has included the production of more than a dozen damning films about UNRWA, including its endorsement of the Palestinian “right of return,” and the translation of dangerous textbooks used in UNRWA schools, that helped bring about the new US policy. This, as well as a chance encounter.

“I happened to sit next to someone from Trump’s transition team in December 2016 at a conference in Jerusalem,” Bedein told the Journal. “I had no idea whom I was sitting next to.

When I found out after the event, I called the official and asked if she would like to see the full UNRWA curriculum. ‘Of course,’ she said. That curriculum wound up in the Oval Office.”

Bedein is nothing if not relentless. He first heard of UNRWA in 1970 as a young immigrant to Israel, learning how a neighbor, a building contractor, had fired his Israeli workers and brought in Arabs who would work for half the salary. The rest of their income, he learned, was subsidized by UNRWA.

“It caught my attention to the point where I decided to take a degree in social work so I could help get these people into a better situation,” said Bedein, who as a child spent summers with his grandparents in Winthrop.

When the First Intifada broke out in 1987, he rented space down the hall from the Government Press Office “to try to help journalists better understand the situation by emphasizing that the refugee issue was self-imposed.” Soon, he was getting funding to examine UNRWA more closely.

“I engaged the services of someone who had been very high up in Israeli intelligence and we discovered that UNRWA’s social services had been taken over by terrorists,” Bedein said. In this way, he claims, funding for UNRWA wound up in the hands of terror groups.

But no one paid any attention and his work went nowhere.

Immediately following the Oslo Accords, signed 25 years ago last week, Bedein said he was told by Yossi Beilin, one of the Israeli negotiators, that once the Palestinian Authority was up and running, it would take responsibility for all services, and that the refugee camps as well as UNRWA would disappear.

“I waited till the PA was set up,” Bedein said, “and its first decision was to keep the refugee camps, keep UNRWA in the camps, and continue demanding a right of return to former homes in Israel by force of arms.”

Quickly, he realized he had been seeking change in the wrong place.

“Our emphasis regarding the schoolbooks had been on both the PA and UNRWA. But the PA had no real supervisory mechanism,” he explained. “That’s when we settled on the concept of bringing things to the attention of UNRWA donor countries, because all UN agencies are supposed to be working toward peace and reconciliation, something UNRWA and its schools clearly were not doing.”

But the real turning point came, he said, in 2016, when an official of USAID, the quasi-governmental US body that works with the PA, admitted – despite claims by the Obama Administration that the textbooks were fine – that it had never examined them. Bedein, in publicizing this startling disclosure, angered a US State Department official who called him a liar.

“More than any other moment in my efforts,” Bedein said, “this inspired me to get working and translate all of the textbooks.”

It was found that some had maps labeling all the land from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea as “Palestine.” Others extolled terrorists. Yet others claimed that Israel was seeking to erase all connections between Islam and Jerusalem, and that the nuclear reactor in Dimona was causing widespread cancer among Arabs in Hebron.

For years, UNRWA has denied the claims made against it. Its spokesperson, Chris Gunness, addressed the textbook issue in speaking to the Journal.

“Where we find there are problematic pages,” he said, “we produce what we call ‘enriched materials.’ When teachers are preparing classes with those pages, they use different materials.”

He was asked what he meant by “problematic.”

“I don’t speak Arabic,” he replied. “I don’t have the details.”

Bedein remains positive that his wrench has found its mark.

“In three trips to DC since the new president came into office, we made it our business to stay in touch with the right policy people,” he said. “My mentor, the late social work professor Eliezer Jaffe, encouraged me a few days before his death in May 2017 that the careful process we had applied would change US UNRWA policy. He was correct.”

Lawrence Rifkin is the Journal’s special correspondent in Jerusalem.