[Commissioned and paid for by the Bedein Center for Near East Policy Research]

Seventy years after its founding with an 18-month mandate to provide emergency aid to the “Palestine refugees,” the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) has grown into a gargantuan $1.2 billion, 30,000-strong “phantom sovereignty”[1] that has done more than any other international actor to perpetuate the “refugee problem” it was established to solve. With the Trump administration slashing its donation to the agency, and the Gulf states and the Europeans demanding greater transparency regarding its finances and operations, UNRWA may at long last be approaching its moment of truth.

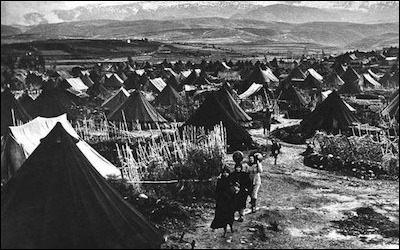

The Original Mandate and Its Demise

The Lausanne Conference—convened by the U.N. Conciliation Commission for Palestine, April 27-September 12, 1949—failed to produce an agreement on resettling the “Palestine refugees” in the host states as was the case with most global conflicts of the time.[2] Consequently, the U.N. established the Economic Survey Mission for the Middle East “to examine economic conditions in the Near East and to make recommendations for action to meet the dislocation caused by the recent hostilities.”[3]

In its report to the U.N. secretary-general on November 16, 1949, the mission recommended that

steps be taken to establish a programme of useful public works for the employment of able-bodied refugees as a first measure towards their rehabilitation; and that, meanwhile, relief, restricted to those in need, be continued throughout the coming year. These recommendations are intended to abate the emergency by constructive action and to reduce the refugee problem to limits within which the Near Eastern Governments can reasonably be expected to assume any remaining responsibility.[4]

The mission specifically stressed the need for an 18-month program of public works, “calculated to improve the productivity of the area,” which was to be carried out in cooperation with the Arab host states and to begin by April 1, 1950.[5] By way of implementing this recommendation, UNRWA was established on December 8, 1949, beginning its operations on May 1, 1950.[6] However, of greater significance than UNRWA’s founding date was its intended termination date: Ration supplies to the refugees were to be suspended by December 31, 1950, with the relief and works program ended by June 30, 1951—by which time the Arab host states would have assumed responsibility for the refugees in their territories.[7]

This was not to be. By the mid-1950s, it had become clear that the works and resettlement program was stillborn. From that point, UNRWA was gradually transformed from a short-lived “relief and works” organization into a permanent, quasi-governmental human development agency providing social welfare services of health care, shelter, and education—the very services that were supposed to be transferred to the host countries.

With the passage of time, UNRWA took on responsibilities traditionally assigned to national state institutions in the fields of education, health, and social services. It began running its camps like a “phantom sovereignty,” to use the words of an Arab commentator.[8] It has done so by utilizing a system of camp services officers (CSOs) gleaned from among camp residents, who, more often than not, were known for their political activism and/or affiliation with the reigning terror groups (Palestine Liberation Organization, PLO, and later Hamas). CSOs’ de facto authority extended, among other things, to cutting off rations for individuals who did not conform to UNRWA’s social and political agenda.

Drifting from the Mandate

By way of disengaging from its specific short-lived original mandate and consolidating its self-styled role as a human development agency, UNRWA adopted a string of measures that ran in stark contrast to international law and practice regarding refugees. This ranged from adopting a unique and highly inclusive definition of a refugee as “a needy person, who, as a result of the war in Palestine, has lost his home and his means of livelihood”; to registering hundreds of thousands of sham “refugees” on its initial rolls; to uniquely making the refugee status hereditary so as to allow its indefinite transference to descendants of the original refugees; to keeping on its rolls refugees who became citizens of the Arab states in which they reside in flagrant violation of the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, which denies this status to any refugee who “has acquired a new nationality, and enjoys the protection of the country of his new nationality.”[9] Thus, for example, some 1.9 million Palestinians in Jordan are registered as “refugees” despite holding Jordanian citizenship and enjoying the same rights and duties as their indigenous compatriots (with “only” 15 percent of them residing in UNRWA camps).[10]

As for the non-naturalized Palestinian “refugees” in the Arab states, as early as September 1965, an Arab League summit in the Moroccan town of Casablanca passed a resolution that conferred on them a string of rights and privileges, including the right to equal employment and freedom of international travel.[11] In Syria, where UNRWA claimed until recently some 450,000 registered beneficiaries, Palestinian “refugees” enjoy most of the rights enjoyed by the indigenous population. They are not confined to refugee camps and can reside anywhere in the country, with a 1956 law stipulating that they are to be treated as Syrians “in all matters pertaining to … the rights of employment, work, commerce, and national obligations.”[12] Accordingly, Palestinians in Syria have not suffered from massive unemployment with only a quarter of them (or 111,208 beneficiaries) living in UNRWA’s refugee camps.[13] And while there are certain differences between the rights of the Palestinian refugees and those of Syrian nationals (e.g., refugees cannot own more than one home or purchase farmland), these have become largely irrelevant given the mayhem and dislocation of the 10-year-long civil war, which have driven an estimated one-third of the Palestinian community to join the general population in fleeing the country.[14]

| A 2017 census of Palestinians in Lebanon provided further proof of UNRWA’s self-serving, inflated figures. |

In Lebanon, where Palestinian refugees enjoy fewer privileges than in other Arab countries, UNRWA has 475,075 registered refugees on its rolls, about 45 percent of whom live in the agency’s twelve refugee camps.[15] But the first-ever official census of Palestinians in Lebanon (published on December 21, 2017) showed that only 174,422 Palestinians lived in the country, providing further proof of UNRWA’s self-serving, inflated figures.[16]

What this means is that there is no justification for continued international support for the millions of “Palestine refugees” who do not meet the standard legal definition of this status and who receive far better treatment than all other refugees. Most do not live in “refugee camps,” which, in any case, should have been disbanded years ago with their occupants moved to conventional neighborhoods—as envisaged by UNRWA’s original mandate.

Political Partisanship, Hate Incitement, and Terror Complicity

In blatant disregard of its original mandate to operate as a politically neutral relief agency, UNRWA’s activities progressively acquired an eminently political dimension that has gradually become embedded in the Palestinian “resistance movement.” In the late 1960s, for example, UNRWA’s acquiescence in the PLO’s takeover of U.N. refugee camps in Jordan allowed the terror group to establish a de facto state-within-a-state and to use it as a springboard for subverting the ruling Hashemite monarchy. This led to vicious internecine strife that culminated in the bloody events of the 1970 Black September in which thousands of Palestinians and Jordanians were killed, and in the PLO’s subsequent eviction from Jordan.

Having substituted Lebanon for Jordan as its basis for terror attacks on Israel, the PLO quickly established yet another state-within-a-state with UNRWA refugee camps providing this terrorist entity with training and deployment bases and serving as its foremost recruitment and indoctrination centers. And as in Jordan, it did not take long before this destructive practice helped trigger in Lebanon one of the worst civil wars in Middle East modern history, which raged for over a decade and claimed hundreds of thousands of lives.[17]

These devastating experiences did not dissuade UNRWA from close collaboration with the PLO in running U.N. refugee camps in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. UNRWA’s education system soon became the effective funder and distributor of the PLO’s anti-Israel and anti-Semitic indoctrination after the terror group seized control over 95 percent of the territories’ population in the 1990s as part of the Oslo “peace process.”

Having committed itself in the Oslo accords to eschewing anti-Israel incitement and to teaching “peace education” to its schoolchildren,[18] the PLO entered into a formal arrangement with UNRWA on August 1, 2000, under which the U.N. agency would adopt PLO-mandated content for all schoolbooks. The agreement further stipulated that PLO-issued schoolbooks would be the sole source of UNRWA’s curriculum. UNRWA offered the unconvincing excuse that adherence to the “host state’s textbooks” was proper, ignoring not only that this violated its obligation to complete neutrality across its educational system but also that the PLO had never been a host state. A series of studies examining UNRWA textbooks and teachers’ guides in 2000-20 uncovered pervasive anti-Israel and anti-Semitic incitement, including:

- De-legitimization of Israel’s very existence and any Jewish attachment to the Land of Israel, based on the supposed exclusive Palestinian right to the land.

- Demonization of Israel and Jews through the use of derogatory terms, references to evil, and attribution of wholesale culpability for any and all Palestinian misfortunes.

- Outright rejection of peaceful coexistence with Israel and calls for violent uprisings against it, with “martyrdom” and jihad taught as bedrock beliefs and values to be striven for.[19]

Small wonder that in June 2013, UNRWA appointed “Arab Idol” singer Muhammad Assaf as its regional youth ambassador though, both before and during his time as ambassador, he released songs and music videos extolling terror as well as dedicated performances to “martyrs” (i.e., slain terrorists). When an Israeli fan called into a radio show featuring Assaf, the UNRWA youth ambassador replied, “I spit on you and Israel.”[20] Yet, despite full knowledge of the anti-Israel, anti-peace, and anti-coexistence messages of Assaf’s musical content and appearances, UNRWA renewed his contract for four more years, blatantly rebutting its own “Peace Starts Here” slogan and a multitude of other declarations.[21]

Aside from sponsoring an ambassador of hate and violence and inculcating Israel- and Jew-hatred in its schoolchildren, UNRWA also helped spread incitement by hosting terror groups’ activities in its installations, notably the Hamas-funded Islamic Bloc’s “student clubs.” Many Hamas terrorists willing to sacrifice their lives in suicide attacks have come from the Bloc’s branches, which had long served as Hamas recruitment and indoctrination hubs. One example is the suicide bomber who murdered thirty people (and wounded another 140) at the Park Hotel Passover massacre of March 27, 2002, which triggered Operation Defensive Shield, Israel’s largest counterterrorist operation since the 1982 Lebanon war.[22] Yet, to date, UNRWA has taken no steps to exclude these clubs from its facilities.

Far worse, when Hamas violently expelled the PLO from Gaza in the summer of 2007 and took control of the Strip, UNRWA became ever more entwined in the Islamist terror group’s activities: It employed numerous Hamas members throughout its humanitarian and educational apparatus. In 2017, for example, two senior UNRWA officials in Gaza were forced to resign after their election to Hamas’s political bureau was publicly exposed.[23] In addition, UNRWA supported Hamas’s terror attacks on Israel. This ranged from regular use of UNRWA schools during summer vacations as paramilitary training camps and the introduction of a military training program into the agency’s schoolwork, undertaken by thousands of students every year as part of their studies; to establishing military facilities and stockpiling weapons and military equipment in close proximity to UNRWA schools—at times inside schools; to digging underground terror tunnels under UNRWA premises; to using UNRWA’s facilities during military encounters with Israel, including transferring weapons and ammunition in UNRWA vehicles, firing rockets and mortar shells on the Israeli civilian population—a war crime in international law—from schoolyards and near-school positions, to booby trapping educational installations.[24]

An Agency Whose Time Has Gone?

UNRWA’s decades-long collaboration with the Palestinian terror organizations and its blatant anti-Israel prejudice reinforce lingering doubts regarding its self-styled apolitical image, its continued necessity, and indeed the legitimacy of its very existence. By comparison, while all post-World War II refugee situations, involving tens of millions of displaced persons (some 16 million in Europe alone) were handled by the International Refugee Organization (IRO), established by the U.N. General Assembly in December 1946 and succeeded in January 1951 by the High Commissioner’s Office for Refugees (UNHCR), the Palestinians received their own relief agency. Furthermore, UNRWA received 110 times the funds allocated to all other refugees throughout the world ($33,700,000 vs. $300,000).[25] Nearly seventy years later, this unique privilege has remained intact, with UNRWA spending four times as much on each Palestinian “refugee” in 2016 as the UNHCR spends on any refugee elsewhere in the world: $246 compared to $58.[26]

| UNRWA spent four times as much on each Palestinian “refugee” in 2016 as the UNHCR spent on any refugee elsewhere in the world. |

And while all other refugee problems were resolved in a timely manner by IRO/UNHCR, with the vast majority of displaced persons (including Holocaust survivors) resettled elsewhere by refugee-welcoming nations, UNRWA built the “Palestinian refugee problem” into a thriving enterprise, one that continually fed the coffers of the Arab regimes and animated Western supporters who professed admiration and support for every nascent post-World War II national movement—save for the Jewish one. In the words of Fred Gottheil:

What is significant about 50 years of UNRWA is … that the majority of Palestinians have reintegrated into the open economies of the Middle East and elsewhere de facto, and that most of those who still remain in refugee camps … do so in the Palestinian homeland. … the refugee status of the overwhelming numbers of Palestinian refugees should have expired somewhere along that 50-year range. … And therein lies the essence of its moral hazard. UNRWA was reinvented to serve political agendas … it became strictly a caretaker agency, dispensing entitlements to refugees who, by UNHCR standards, would not be so defined. All this at enormous cost.[27]

A number of myths have served to perpetuate UNRWA’s self-serving raison d’être as the agency morphed into an enterprise never envisioned by its original mandate, including “impoverishment” of refugees—despite rejection of true rehabilitation efforts funded in the billions of dollars; “occupation”—despite the fact that only a small part of the entire “refugee” population resided in Israeli-controlled territories after 1967, and that 95 percent of them had been transferred to Palestinian rule by 1996-97; and “economic strangulation”—despite the fact that the West Bank and Gaza economy enjoyed an unprecedented economic boom due to the vast opportunities provided by Israel’s control of these territories in 1967-97.[28] As these myths melt away—or at the very least are no longer sanctioned by Western and Gulf governments—UNRWA reforms must respond to the growing calls for transparency regarding expenditures, governance, and the education of its beneficiary children.

First Step to Reform

Perhaps the most important step UNRWA can take is to adopt the same standards as the UNHCR. Specifically, UNRWA must take real measures toward the ultimate resettlement of refugees in the host states as envisaged by its original mandate, so as to transform them from passive welfare recipients into productive and enterprising citizens of their respective societies. This is not something that can occur overnight, or even in a few years, but unless a realistic 10-year resettlement plan is crafted, the ever-increasing numbers of perpetual “refugees” kept in squalid camps will never decrease.

| UNRWA must take real measures toward the ultimate resettlement of refugees in host states. |

While there have been numerous studies, audits, and assessments of UNRWA’s operational deficiencies—from resistance to reform, to cover-up of gender issues and sexual abuse by UNRWA workers, to overall human resource and commercial transaction mismanagement—no independent, external financial audit has ever been demanded by the donor states to account for the use, or possible abuse, of their decades-long massive donations to UNRWA: How much of this money is spent on anti-Israel and anti-Semitic incitement through funding of PLO-dictated textbooks and teachers’ guides? How much money is spent on wages for Hamas-affiliated employees who are not legally permitted to be on UNRWA’s payroll, and how much on providing facilities for summer training of schoolchildren in terrorism? And above all, how much donor money is spent on perpetuating the Palestinians’ “refugeedom” rather than to “start [the refugees] on the road to rehabilitation and bring an end to their enforced idleness and the demoralizing effect of a dole,” to use the words of the 1949 Economic Survey Mission, whose recommendations informed UNRWA’s original mandate.[29]

Donor states are not only entitled to know how their taxpayers’ monies are being spent but have an obligation and responsibility to assure that they are spent on the purposes for which they were donated, and not on those that violate U.N. directives or international law. To date, this has not been done. Only an audit by the donor states will empower reform.

Conclusion

The time has come for the geopolitical realities of the 2020s to be confronted head-on. The PLO, while clinging to its eternal rejectionism as evidenced among other things by its “destroy the Zionist entity” school curriculum, is nevertheless not the PLO of Yasser Arafat. Hamas, though still committed to its ultimate goal of destroying Israel, is amenable to suspension of hostilities in return for humanitarian aid, either directly (e.g., regular flow of Qatari money to Gaza) or indirectly (e.g., training Gaza medical students in Israeli hospitals, hospitalizing serious COVID-19 patients in Israeli hospitals).[30] And the Arab states seem less inclined than ever to make their national interests captive to the whims of the Palestinian leadership as evidenced by the recent normalization accords between Israel, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and Sudan and the strengthening relations between the Jewish state and the other Arab states.

In addition, UNRWA faces its greatest challenge in decades as Washington, its largest donor, slashed its financial support while the U.N.’s own oversight watchdogs investigated the agency’s financial irregularities as it pleads impoverishment over a deficit figure variously ranging between $332 million and over $1 billion.[31] But UNRWA’s plea seems to strike a weaker chord even in the European Union where the narrative of the perpetually impoverished Palestinian refugees seems to have worn thin and where the unquestioned propping up of UNRWA’s failed mission is coming under growing scrutiny by those who used to be its most vocal champions.

As the Arab and Western states face their long-overdue obligations to help proactively to resolve the Palestinian “refugee problem,” the agency’s 70-year-long “works” must either profoundly reform or become irrelevant.

Ron Schleifer, senior lecturer at Ariel University’s School of Communication, specializes in the Middle East and communication issues. His book on foreign media coverage of Israel and the Palestinians is forthcoming by Rowman and Littlewood.

Yehudah Brochin is a U.S.-licensed attorney who has been a contributor to Israel-advocacy projects and organizations in the U.S. and Israel. He has taught business law at the Jerusalem College of Technology and has authored articles on transparency and risk management.

[1] Sari Hanafi, “UNRWA as a ‘Phantom Sovereign’: Governance Practices in Lebanon,” in Sari Hanafi, Leila Hilal, and Lex Takkenberg, eds., UNRWA and Palestinian Refugees: From Relief and Works to Human Development (Abindgon, U.K.: Routledge, 2014), pp. 129-42.

[2] “Final report of the United Nations Economic Survey Mission for the Middle East,” U.N. Conciliation Commission for Palestine (Lake Success, N.Y.: United Nations, Dec. 28, 1949).

[3] “First Interim Report of the United Nations Economic Survey Mission for the Middle East,” Chairman of the United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine, submitted to the U.N. General-Secretary, Nov. 16, 1949, p. 15.

[6] “General Assembly Resolution 302. Assistance to Palestine Refugees,” United Nations, A/RES/302 (IV), Dec. 8, 1949, art. 6.

[7] “First Interim Report of the United Nations Economic Survey Mission for the Middle East.”

[8] Hanafi, “UNRWA as a ‘Phantom Sovereign.'”

[9] Constitution of the International Refugee Organization, sect. D (b), p. 817; “Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees,” arts. 1/C (3), 1/E; Efraim Karsh, “The Privileged Palestinian ‘Refugees,’” Middle East Quarterly, Summer 2018.

[10] “Human Rights Watch Policy on the Right to Return,” Human Rights Watch, New York.

[11] Sherifa Shafie, “Palestinian Refugees in Lebanon,” Palestinians in Europe Conference, Nov. 30, 2001.

[12] “Treatment and Rights in Arab Host States: Human Rights Watch Policy on the Right to Return.”

[14] See, for example, Aljazeera TV (Doha), Mar. 23, 2016.

[15] “Where we work,” UNRWA.

[16] Yakov Faitelson, “How Israel’s Jewish Majority Will Grow,” Middle East Quarterly, Fall 2020.

[17] Jalal al-Husseini, “UNRWA and the Palestinian Nation-Building Process,” Journal of Palestine Studies, Winter 2000, pp. 51-64.

[18] “Agreement on the Gaza Strip and the Jericho Area, May 4, 1994,” art. XII (1); “Israeli-Palestinian Interim Agreement on the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, September 28, 1995,” art. XXII (1, 2); “The Wye River Memorandum, October 23, 1998,” art. 3 (a, b), in Geoffrey W. Watson, The Oslo Accords: International Law and the Israeli-Palestinian Peace Agreements (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), pp. 334, 363, 379.

[19] See, for example, Arnon Groiss, “The Attitude to the ‘Other’ and to Peace in Palestinian Authority Schoolbooks: An Update Based on the 2019 Books,” Center for Near East Policy Research, Jerusalem, Aug. 28, 2020; Groiss, “Israel, Jews and Peace in Palestinian Authority Teachers’ Guides,” The Meir Amit Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center, Ramat Hasharon, June 8, 2020.

[20] Al-Arabiya News Channel (Dubai), Jan. 5, 2016; The Algemeiner (Brooklyn), Jan. 7, 2016.

[21] “Our Youth Ambassador, Mohammed Assaf,” UNRWA; “‘Arab Idol’ Winner Mohammad Assaf named UNRWA Regional Youth Ambassador for Palestine Refugees,” June 22, 2013.

[22] Jamie Chosak and Julie Sawyer, “Hamas’s Tactics: Lessons from Recent Attacks,” The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, Washington, D.C., Oct. 19, 2005.

[23] “Resignation of Suhail al-Hindi, chairman of the UNRWA staff union in the Gaza Strip, after exposure of his election to Hamas’ new Gazan political bureau,” The Meir Amit Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center, Ramat Hasharon Apr. 24, 2017.

[24] “Hamas and other terrorist organizations in the Gaza Strip use schools for military-terrorist purposes,” The Meir Amit Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center, July 20, 2014; “UNRWA Exposed Another Tunnel under One of the Schools It Operates in the Gaza Strip,” Amit Center, Nov. 1, 2017; Uri Akavia, “UNRWA’s Conduct Severely Undermines the Neutrality and Credibility of the UN,” Kohelet Policy Forum, Jerusalem, Nov. 29, 2017.

[25] Karsh, “The Privileged Palestinian ‘Refugees.'”

[26] Itamar Eichner, interview with Amb. Ron Prosor, Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya, Aug. 27, 2017.

[27] Fred Gottheil, “UNRWA and Moral Hazard,” Middle Eastern Studies, May 2006, p. 418.

[28] Efraim Karsh, “What Occupation?” Commentary Magazine, July/Aug. 2002.

[29] “Final report of the United Nations Economic Survey Mission for the Middle East,” p. vii.

[30] See, for example, The Times of Israel (Jerusalem), Jan. 2, Apr. 11, 2020.

[31] Arutz Sheva (Beit El and Petah Tikva), Mar. 6, 2020.