The PLO is in decline and the Palestinian Authority has retreated, leaving eastern Jerusalem Arabs caught in a vortex of conflicting identities and loyalties; between the influence of radical Islamic forces and the counter-gravitational pull of integration into Israeli society. Ongoing engagement with local Arab community leaders suggests that there is room for hope and much to yet accomplish.

“The air I breathe, the water I drink, and the bread I eat—all of them are infused with politics, religion, and countless sensitive points. … Nevertheless, after decades of living under Israeli rule I simply want to breathe, to inhale and feel like a welcome resident of this city.” This is how an eastern Jerusalem Arab social activist described the reality of his life in the city when we met with him in the a-Tur neighborhood where he lives.

The sharp contrast between the strong national and religious symbolism that Jerusalem (or al-Quds, by its Arabic name) holds for its Arab residents, on the one hand, and their accelerated integration into Israeli society, both in the city and elsewhere, on the other, has entangled them in a thicket of contradictions.

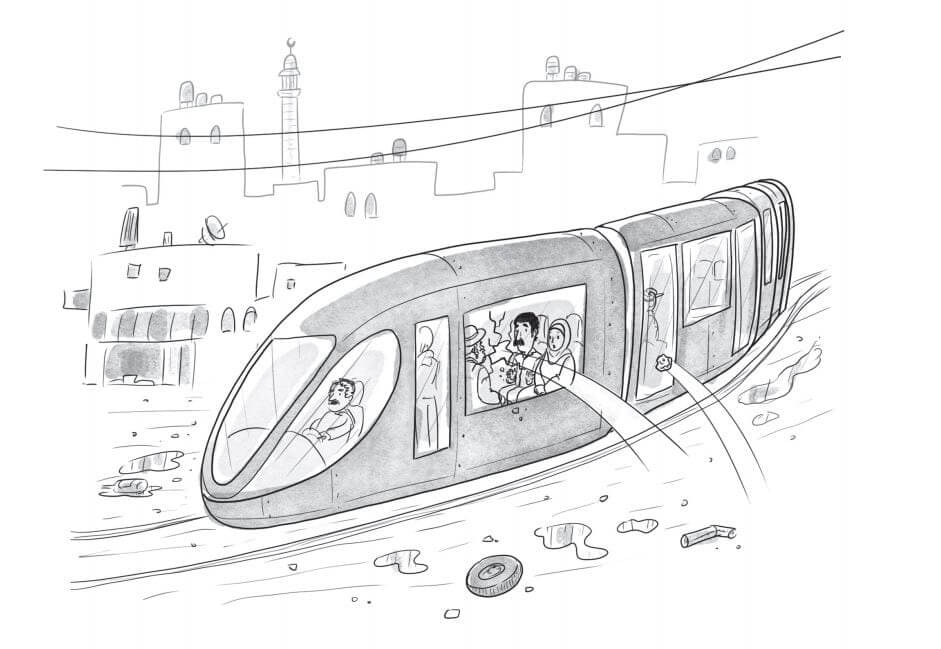

Eastern Jerusalem Arabs assert their Palestinian national identity while showing an unprecedented demand for Israeli citizenship; throw stones at the light rail while using it; harass visitors to Hadassah Hospital on Mount Scopus but value the care that Arabs receive in its clinics and wards; protest the enforcement of planning and building laws in Arab neighborhoods while calling for an increased police presence there to maintain public order; campaign against any manifestation of normalization with Israel in tandem with a tremendous interest in learning Hebrew and an increasing preference for the Israeli rather than the Palestinian matriculation certificate.

They also fly the flag of Palestine and spray-paint nationalist slogans in praise of Fatah on the walls of buildings, while expressing vicious criticism of the chairman of Fatah and the Palestinian Authority, Abu Mazen, on the social networks. And alongside the growing power of conservative Islamist forces in the public domain, many eastern Jerusalem Arabs have become more lax in their observance of family values and tradition.

The Palestinian historian Edward Said asserted that “no people – for bad or for good – is so freighted with multiple, and yet unreachable or indigestible, significance as the Palestinians. Their relationship to Zionism, and ultimately with political and even spiritual Judaism, gives them a formidable burden as interlocutors of the Jews. Then their relationships to Islam, to Arab nationalism, to Third World anti-colonialist and anti-imperialist struggle, to the Christian world with its unique historical and cultural attachment to Palestine…all these put upon the Palestinian a burden of interpretation and multiplication of selves that are virtually unparalleled in modern political or cultural history”[1].

If we accept Said’s thesis, there is no better example of the Palestinian burden of interpretation and multiple identities than the current situation in Eastern Jerusalem. As we see it, the historical and geopolitical circumstances that prevail today have brought the multiple identities to a historical crossroads, where Eastern Jerusalemites will have to decide whether they are going to integrate into Israeli society or defy it, as we will describe below.

In recent years, the authors of this article have been in direct and intense contact with the residents of Eastern Jerusalem by virtue of our membership on the municipal team that oversees all of Jerusalem City Hall’s interactions with the Muslim and Christian populations of the city. In our work, we are exposed to the full glory of the celestial Jerusalem, while at the same time we experience with unparalleled intensity the thicket of contradictory interests, tensions, and disagreements that inform daily life in the earthly Jerusalem.

We have become familiar with a fascinating world whose intricacies are known to few Israelis, despite its importance to and central place in the Israeli discourse. The present article attempts to open a window onto this world, generally hidden from Israeli readers, and enhance their understanding of the processes taking place there. Its main thrust is an analysis of the Palestinian Arab side, but towards the end we will bring up several alternatives that Israel might choose for devising a policy to deal with the challenges and opportunities that currently exist in Eastern Jerusalem.

Eastern Jerusalem: Background

“Eastern Jerusalem” is the term applied (not very accurately, it must be said, from the geographical point of view, because it also includes territory north and south of the city) for the neighborhoods within the municipal jurisdiction of Jerusalem that are beyond the Green Line. They cover about 70 sq. km. In fact, the area of pre-1967 Jordanian Jerusalem was only 6.4 sq. km, in the Old City and its immediate environs. After the Six Day War, Israel annexed an additional 63.6 sq. km, consisting mainly of 28 Arab villages. The Arab population of the newly united and expanded Jerusalem in 1967 was about 70,000; alongside the 197,000 Jew, they constituted 26.5% of the city’s population.

Residents of eastern Jerusalem have the legal status of permanent residents, which in practice is the same as that of foreign nationals who want to live in Israel for a protracted period. This status grants them the right to live and work in Israel without the need for special permits (unlike the Palestinians of Judea and Samaria). It also entitles them to benefits under the National Insurance Law and the National Health Insurance Law. As permanent residents, they are eligible to vote in municipal but not in national elections. If they leave the country for more than seven years they risk losing this status[2]. From time to time, they may be required to prove that the center of their lives is indeed Jerusalem to retain their status. A permanent resident who marries a person who lacks this status and wishes to live together with the spouse in Jerusalem must submit a family unification request. This phenomenon is found mainly in the villages in the south-eastern part of the city, where there are strong family and clan ties between the residents of the villages on the Israeli and Palestinian sides of the line (for example, Sawahra al-Gharbiya on the Israeli side, and Sawahra al-Sharqiya on the Palestinian side).

Permanent residents can apply for Israeli citizenship. This requires them to swear allegiance to the state, submit proof that they do not hold any other citizenship (many residents of Eastern Jerusalem hold Jordanian citizenship), and demonstrate some fluency in Hebrew.

The permanent residency and the intermediate status it provides, on the one hand, and the dependence on social benefits (national insurance) and healthcare (Israeli HMOs and hospitals) on the other, is a key to understanding the circumstances of life for the Palestinians in eastern Jerusalem.

Deep research studies and public opinion surveys conducted among them reveal that safeguarding their permanent resident status and remaining eligible for national insurance benefits and healthcare, rank high among the reasons that Palestinians prefer to live within the municipal boundaries of Jerusalem, even though they could probably find cheaper and better housing elsewhere.

This group currently numbers some 320,000 persons (to which must be added about 50,000 residents of Judea and Samaria who reside in the city illegally or by virtue of family reunification); they constitute about 37% of the Jerusalem population and 20% of the Arabs within Israel’s borders. Jerusalem is home to the largest concentration of Palestinian Arabs between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean (excluding Gaza). By way of comparison, the population of Ramallah is about 280,000 and of Nazareth, the largest Arab town in Israel, 75,000. Regarding religion, the majority are Muslims, with only a small minority of Christians (10,000–15,000).

About 100,000 of the Eastern Jerusalem Arabs live in neighborhoods that lie within the municipal boundaries of Jerusalem but are on the other side of the security fence (constructed around Jerusalem between 2002 and 2007). These neighborhoods are marked by severe overcrowding and extensive illegal construction, to a much greater extent than the neighborhoods inside the fence. As we shall see, the fence has cut off the Jerusalem Arabs who live inside it from Ramallah and the West Bank and intensified their links to the employment, welfare, healthcare, and economic infrastructure of West Jerusalem, and consequently to the city’s Jewish sector.

The numerical growth of the Arab population has been powered not only by a relatively high rate of natural increase (though this has tapered off in recent years and is now almost the same as the rate for the Jews, which is on the rise), but also by the migration to Jerusalem of thousands of Palestinian families from Judea and Samaria (chiefly Hebron). Today such families make up the lion’s share of the Arab population of Jerusalem.

There are villages and neighborhoods, such as Ras al-Amud and Abu Tor, where there is a large majority of Hebronite families. These families have set down roots in Jerusalem, where they maintain the old network of tribal and clan affiliations, reflected in their commercial and marriage ties, modes of resolving disputes and disagreements, and so on.

The native Jerusalem Arabs still live in the city, of course, including the aristocratic families—the Nashashibis, the Husseinis, the Nusseibehs, and others. This group now finds itself in a perpetual struggle to maintain its place and status in community, public, and economic life, given the competition with immigrants from Hebron and the rest of the West Bank and the influx of “1948 Arabs,” meaning those from the villages and towns of other parts of Israel, who in the last few decades have flocked to Jerusalem to study or work and stayed on. This last group lives both in the higher-class Arab neighborhoods and Jewish neighborhoods such as Pisgat Ze’ev and French Hill. The “authentic” Jerusalemites are quite upset by the fact that both the Hebronites and Arabs from the north are nibbling away at “their” Jerusalem.

The Arab Christians, whose numbers have dwindled over the years, congregate in communities where they feel more secure against harassment and assault by hostile Muslim elements. In addition to the long-settled Christian communities in the Old City, there are more recent concentrations in better-off neighborhoods, such as Beit Zafafa, Sharafat, Beit Hanina, and Shuafat. Despite the Christians’ relatively small numbers, the churches that extend their protection to the Christian communities are a major force in the city. The churches play an important political role by making the international community aware of their opinion about events in Jerusalem, chiefly regarding freedom of religion and worship. They have a major influence on tourism to Israel and Jerusalem, much of which consists of Christian pilgrims. Finally, they own vast tracts of strategic land in both the western and eastern sections of the city.

The Arabs of Jerusalem are relatively young and impoverished. According to the National Insurance Institute, 83.4% of the children in Eastern Jerusalem are below the poverty line, as against 56.7% of Israeli Arab children and 39.7% of the children in West Jerusalem. Monthly per capita income in Eastern Jerusalemites is only about 2000 sheqels, as against nearly 5000 sheqels in the western part of the city. Regarding employment, although Eastern Jerusalem men have a very high labor-force participation rate (chiefly in manual labor and services), that of women is much lower, about 14% (which may be compared to 32% among Arab women in the villages of the Galilee). In this context, it is important to note that Eastern Jerusalemites are not monolithic, and that there is a fairly broad span of socioeconomic levels among the neighborhoods.

As for the quality of infrastructure in the Arab neighborhoods, it is obvious to anyone who walks or drives through them that they suffer from inadequate roads, sewers and drainage systems, sanitation, education, recreational activities, welfare services, community services, culture, and sports. In recent years the Jerusalem municipality, with assistance from the national government, has undertaken a major effort to reduce the disparities and improve the level of services and infrastructure, with the emphasis on roads and classroom. It must be remembered, however, that this effort was launched after decades of neglect, going back to the period of Jordanian control.

As for the community leadership in Eastern Jerusalem, over the years there has been a very significant erosion in the status of the veteran mukhtars, except in some of the villages in the south-eastern part of the city (which are more tribal and Bedouin in nature) and a few villages such as Issawiya and Beit Zafafa, where the mukhtars still have real power. The shoes of the veteran and conservative leadership are being filled by young and dynamic leaders who are less inclined to placate the Israeli authorities and confront the latter with the contemporary civic discourse of rights. This group includes educators and social workers, community activists, merchants and businesspeople, and others, many of whom attended Israeli institutions of higher education and/or are in intensive interaction with Israeli society.

There has also been an increase in the clout of the religious leadership, which has an important say about the conduct of life in Eastern Jerusalem, and especially with regard to the Holy Basin, the Haram a-Sharif (the Temple Mount compound), and the al-Aqsa Mosque.

Palestinian Nationalism in Jerusalem

The peak moment of Palestinian nationalism in eastern Jerusalem came during the ten years that preceded the start of the first Intifada. During that decade, the PLO and especially the Fatah movement increased their political control of the city, as reflected by the establishment of Fatah branches in every neighborhood and in the nearby villages. In addition to the neighborhood offices and local committees, a long series of Jerusalem-based organizations—youth groups, student cells, trade unions, and women’s associations—identified themselves with Fatah and operated under the umbrella of the Tanzim. There was a sharp increase in the number of PLO-identified newspapers were published in Jerusalem. The organization made its mark in the cultural arena, too, with the establishment of the Palestinian national theater al-Hawakati and the founding of federations of Palestinian authors and artists.[3]

In those years, the Palestinian nationalist political establishment in the Jerusalem was headed by Faisal Husseini, the scion of the aristocratic Husseini family and son of Abd al-Qadr Husseini, the commander of the Arab forces on the Jerusalem front during the War of Independence. He managed to unite the majority of Arabs in eastern Jerusalem behind his leadership. Husseini operated with little hindrance by the authorities and openly held political meetings and conferences. From his headquarters in Orient House, a building owned by his family, he planted deep roots for Palestinian nationalism in eastern Jerusalem while strengthening the Fatah political infrastructure.

The many national institutions established in eastern Jerusalem during that period could be found all over the city, enjoyed significant freedom of action, and disposed of vast budgets, mainly the largesse of Arab countries. All this was compatible with the PLO’s hegemonic position at the head of the Palestinian cause on both the Arab and international fronts. The PLO and Fatah placed the issue of Jerusalem at the center of their activity, engaging in extensive operations there and augmenting their support among its residents.

The surge of Palestinian nationalism in Jerusalem came to a large extent at the expense of identification with Jordan, which had ruled the eastern part of the city until 1967. The erosion in the Hashemite Kingdom’s status was exemplified by Palestinian national elements’ takeover of key positions in “Jordanian” institutions, such as the Shari’a religious court and the Waqf. In many cases this was done with the tacit approval of Amman, which, realizing that this trend was consistent with the dominant sentiment among Jerusalem Arabs, sought to please them.

The outbreak of the first Intifada in 1987 offered a golden opportunity for the PLO and Tanzim in the city. They exploited it to flaunt their power and grip on the population, and organized a series of mass protests in the neighborhoods as well as frequent commercial strikes. The local leadership in Jerusalem, headed by Faisal Husseini, drew closer to the leadership in Tunis and its members acquired greater weight in the front ranks of the Intifada.[4]

Husseini also took part in the Madrid talks in 1991, where he was instrumental in placing the topic of Jerusalem on the negotiating table as the representative (albeit unofficial) of the city. From there it was a very short way to turning Husseini’s Orient House offices into a pilgrimage site for international diplomats and senior politicians and into the effective headquarters of the PLO in Jerusalem. As such, it was where many residents of Eastern Jerusalem turned for assistance in various public and private matters.

There is no doubt that the establishment of the Palestinian Authority was a historic watershed that raised very high expectations among the residents of Eastern Jerusalem in general, and the supporters of the PLO in particular. Thousands of them went out to greet Arafat when he arrived in Jericho after his long years of exile in Beirut and Tunis. Those Eastern Jerusalemites saw his arrival and the initial consolidation of the Palestinian Authority as the start of a new era that was expected to produce positive and welcome change. After more than two decades of uncertainty about their own and the city’s status, the residents of Eastern Jerusalem saw the first buds of a diplomatic process in which the Palestinian Authority was the channel for realizing their national and political aspirations.

In fact, from the very first days of the Palestinian Authority its officials did everything they could to assert their control in Eastern Jerusalem. The various Palestinian security services enlisted many local Fatah activists in every neighborhood, and these new recruits endeavored to impose their rule there while demonstrating loyalty to the leadership in Ramallah. They also established a police force to resolve local disputes and co-opted many neighborhood dignitaries and mediators to their ranks. The idea was to establish themselves as the national address for the residents of Eastern Jerusalem and as the source of political authority, with the power to ensure their well-being and future.

But many of the hopes that the residents of Eastern Jerusalem attached to the national leadership in Ramallah and the newly established Palestinian Authority were soon dashed. It was precisely in those years that the split between the local leadership in Jerusalem (the “internal” PLO) and those who had returned from Tunis (the “overseas” PLO) gaped wider. The senior echelons of the PA, who, as stated, recruited the traditional Fatah activists in the neighborhoods, also did their utmost to clip the wings of Faisal Husseini and Orient House, fearing they might serve as an alternative power center. Arafat froze significant chunks of the budgets allocated to Orient House and other Jerusalem institutions. Several important institutions left the city for Ramallah, which gained influence at Jerusalem’s expense. These processes provoked great frustration among many PLO supporters in Jerusalem, who began to fear that the national leadership had effectively abandoned them.

There can be no doubt that Faisal Husseini’s death in Kuwait in 2001 was an additional catalyst of the decline in the PLO’s standing in the city. Even today his close associates blame Arafat, who feared Husseini as a potential rival for power, for scuttling his project time and again, causing him great pain and deep disappointment. Husseini’s departure from the scene left a huge vacuum in the city’s political leadership and caused many Eastern Jerusalemites to distance themselves from the PA. They did not lack reasons to step back and even to sever their ties with PA institutions. The belligerent and sometimes even violent behavior of PA personnel, along with the epidemic of reports of corruption in the higher echelons and abuse of power and authority, had a strong impact on public opinion in Eastern Jerusalem.

Although the second (al-Aqsa) Intifada hoisted the banner of the Palestinian struggle over Jerusalem and the Temple Mount, in practice it seems to have led to the almost total disintegration of the Palestinian Authority in the city and the realization that for the foreseeable future there is no alternative to Israeli control of the city. The closure of Orient House delivered a severe blow to the efforts by PLO agents to operate openly in the city. The security fence constructed in response to the intifada cut off the city from its socioeconomic hinterland—the Palestinian villages in the Jerusalem perimeter (Abu Dis, Azariya, al-Ram, and others)—as well as from the PA’s power centers in the West Bank. This was another and almost the final stage in the progressive empowerment of Ramallah at the expense of eastern Jerusalem.

While the former has developed into a vibrant city, teeming with life, Jerusalem has become increasingly marginal for the Palestinians, certainly from the socioeconomic perspective. A closer look at these processes indicates that, as we have noted, they have reinforced a separate Eastern Jerusalem identity. From this it was but a short step to the rise of other actors in Jerusalem, who do not promote Palestinian nationalism and offer a clear alternative to the PLO’s path. We will discuss them below.

In Jerusalem today, the PLO and Fatah are still beset by the ailments described above. The allegations of corruption and gangsterism by their people continue to be heard morning noon and night; and all the internal divisions remain as before. On one side stand the veteran Jerusalem families, such as Husseini and Nusseibeh, whose influence was undercut by the death of Faisal Husseini and the closure of Orient House; on the other side are the Hebronites, who currently constitute a majority of the residents of eastern Jerusalem. The historical rivalry and mutual hostility between these two groups have never ceased, and can be viewed as the current version of the old tension between Arafat and his people on the one hand and Faisal Husseini and his people on the other.[5]

In many of our conversations with members of the old elite, we hear their anger and frustration that Abu Mazen has continued Arafat’s policies of allocating miniscule budgets to benefit the residents of Eastern Jerusalem, as compared to the Palestinian towns on the West Bank. The movement, described above, away from the power centers of the Palestinian Authority, and sometimes even from the PLO and Fatah, persists today and with even greater force.

With this background, it is interesting to see how the agents of the PA and Fatah in Jerusalem are striving to recover their lost prestige. On the one side, we see members of the Tanzim, led by Adnan Ghaith, who take a rigid position against any normalization with Israel and declare their support for the armed struggle, sometimes coming into open conflict with Abu Mazen and his people. Ghaith and company, worried by the slow hemorrhaging of their supporters to other movements, mainly Islamist, and trying not to be left behind, have adopted a more radical line and employ more violent rhetoric than before.

On the other side, from time to time we hear how Adnan Husseini, another member of the family and currently the governor of the Jerusalem district and minister for Jerusalem affairs in the Palestinian Authority, is investing significant energy in the campaign against the “Judaization” of Jerusalem, in both the local and the international arenas. Husseini devotes the bulk of the funds at his disposal to public campaigns and litigation against the sale of property to Jews, against the adoption of the Israeli curriculum by schools, and against the demolition of illegal structures in the eastern part of the city, while emphasizing the value of steadfast attachment to the land (sumud).

From time to time, as we hear, Husseini allocates funds to merchants in the Old City who are in economic straits, in an attempt to mollify their fury with the PA. In general, one can say that PA activity in the city today is almost totally restricted to the symbolic dimension—the campaign against normalization and acceptance of the Israeli presence in the eastern part of the city and the “Judaization” of Jerusalem.

Despite these steps, it seems that neither the Tanzim nor PA people are making a real contribution to improving the lives of eastern Jerusalemites. Despite their repeated attempts to win points in public opinion and to stand in the forefront of political and media campaigns with symbolic value, they do not seem to have recaptured the place they once held in the hearts of Eastern Jerusalemites.

The proof is that in the recent Fatah leadership elections in the a-Tur neighborhood, considered to be one of the movement’s strongholds, only 200 persons turned out to vote. In fact, the movement is scarcely signing up new members these days, neither in a-Tur nor in other neighborhoods.[6]

The Rise of the Islamic Religious Identity

Now we can state explicitly what we have only hinted at thus far: the Islamic movements are gaining strength at the expense of the secular nationalist movements.

One need only look at the Middle East as a whole to appreciate that this phenomenon is not unique to the Palestinians or to the Arabs of Jerusalem but is an almost universal development. The collapse of secular nationalist frameworks and rise of a broad spectrum of religious, ethnic, or tribal identities, which frequently extend across the borders of nations and states, is a fait accompli throughout the region. This continuum of old-new identities includes the ideology of the Muslim Brotherhood along with Salafi concepts, as well as visions of the restoration of the Islamic caliphate.

It may be that these processes are taking place more quickly in Jerusalem, whose population is a mosaic of individuals and communities with very different backgrounds—Hebronites versus “native” Jerusalemites, urbanites against villagers and Bedouin, and so on. The fact that Israeli law applies to all of them has gradually forged a shared destiny, but even today, 50 years after this legal change, the political rivalries and competition between different interest groups are as fierce as ever. Against this background, we can understand why the common national identity is so fragile and under constant assault.

As we see the situation in eastern Jerusalem, the progressive alienation from the classic nationalist frameworks is creating an array of what can be called hybrid identities. On the one hand, there is the specifically local dimension of a strong and direct bond to the city in general and to the Temple Mount in particular. But there is also another dimension that goes beyond the local Palestinian interest and adopts a broader historical perspective. These two dimensions are not mutually exclusive, but to a large extent complementary and supportive of each other.

The emphatic link to Jerusalem and the Temple Mount feeds a yearning for their glorious (if somewhat imaginary) Islamic Arab past, along with a desire to restore that historical order. From the perspective of Eastern Jerusalemites, when there is no alternative to Israeli control of the city visible on the horizon, and when life supplies repeated challenges and internal crises, the adoption of a hybrid identity becomes a logical and natural step.

The main beneficiaries of the changes taking place among the population of Eastern Jerusalem are undoubtedly the elements identified with Hamas, with the northern faction of the Islamic Movement in Israel, or with the Muslim Brotherhood in its wider context. In the elections for the Palestinian legislative assembly in 2006, Hamas won all four seats allotted to Muslims in the Jerusalem district. In a survey conducted by the Washington Institute in June 2015, 39% of Eastern Jerusalemites said that Hamas best represented their political affiliation. In addition, 37% of respondents that said that “being a good Muslim” ranked at the top of their scale of personal values.[7]

It is important to emphasize that when we speak about Hamas and similar groups in eastern Jerusalem we are not talking about official, defined, and structure organizations. Instead, we must point to a series of civic associations, nonprofits, and grassroots organizations, sometimes at the neighborhood level and sometimes more extensive, that do not explicitly wave the Hamas flag but make no bones about their identification with the movement and its values. Sometimes their members are openly affiliated with Hamas, with strong ties to the leadership in Ramallah; sometimes they identify with figures such as Ra’id Salah, the head of the northern faction of the Islamic Movement in Israel, or his ally Ekrima Sa’id Sabri, the former grand mufti of Jerusalem (appointed by the Palestinian Authority) and today the most prominent representative of the Muslim Brotherhood in the city. All of them share the Brotherhood’s basic ideology, but are distinguished by their centers of support, funding, and identification, as well as the emphases of their activity. For example, as we will see later, today Sabri and Salah are more in tune with Turkey and Qatar than with the Hamas leadership in the West Bank or Gaza, and thus are more identified with the Brotherhood’s global network.

Because Israel bans Hamas activity in the city, much of it takes place more or less sub rosa, with the operatives’ organizational and movement affiliation left unsaid. Because the Hamas leaders have to work in the shadows, over the years we have seen Salah and his people in the forefront of public campaigns, chiefly with regard to the Temple Mount. Now that the northern faction of the Islamic Movement has been outlawed, too, Sheikh Sabri has been left the main player on the scene. By the nature of things, the implications of the outlawing of the Islamic Movement will become clear only over time. In addition to the possibility that its members will continue their efforts underground, in some guise or other, it is also possible that new actors will enter the lists; we will discuss some of them below.

The individuals and organizations in the city that are identified with Hamas and the Muslim Brotherhood devote most of their time and energy to dawa (missionary) activities, mainly charitable enterprises and educational programs to attract the young to Islamic values. The underlying rationale here is that only a major investment in the education of future generations of Muslims will make it possible, when conditions are ripe, to restore the historical Muslim control of Jerusalem and its holy places. Alongside this dawa work, Islamist elements, are successfully entrenching their hold on neighborhood power centers that were formerly identified with and the Palestinian Authority. For example, parents’ committees in Eastern Jerusalem have become an arena of skirmishes between Hamas and Fatah, with the former frequently coming out on top.

Other power centers that Islamists have wrested control of in some neighborhoods include neighborhood action committees, rapid-response teams, teen committees, and young adult and women’s movements. The Islamists are strongest in the south-eastern neighborhoods, which have a more traditional and clan-based population and offer fertile ground for processes of the sort. Of course, these efforts are in addition to the groups’ extensive activity regarding the Temple Mount, on which we will expand below.

As noted, these groups’ main thrust is dawa projects that target chiefly teenagers, women, and children. But it is obvious to all that a direct line often stretches from civic dawa to radicalization and active enlistment in the armed struggle against Israel. The strongest manifestation of this is the groups’ lively presence on the social networks. During the last two years, we have encountered a long list of Facebook groups and pages based in eastern Jerusalem that have tens of thousands of followers, mainly among the young. Many of these are Islamist in nature, maintained under one cover or another; they glorify terrorists, martyrs, and prisoners, and explicitly call for violent resistance to Israel. For example, pages of this sort distributed and promoted hashtags such as the “knife intifada,” “stand up and resist,” and “stab.” Here we see repeatedly how the libel that al-Aqsa is in danger serves as a tool for propaganda and incitement, and for disseminating the incredible volume of disinformation related to Israeli actions on the Temple Mount and in general.

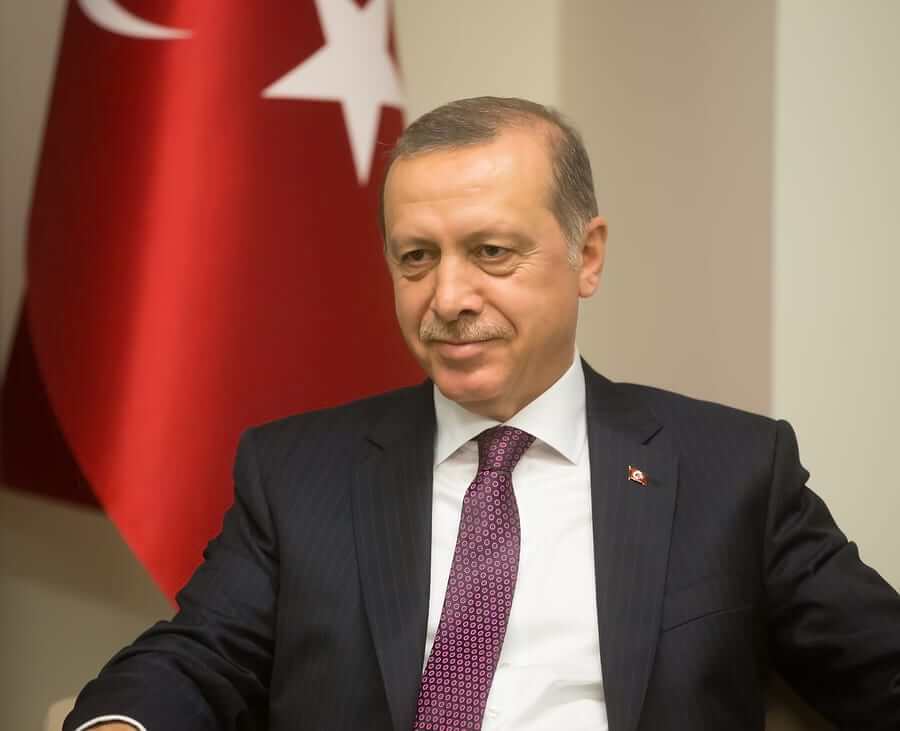

To complete the picture, we must take note of another player that backs those affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood in Jerusalem and on the Temple Mount and benefits from their increased strength—Turkey. The mounting involvement of Erdoğan’s Turkey, which is now the worldwide Brotherhood’s main patron, attests that developments in Jerusalem are part of the broader process of consolidating Turkish regional hegemony at the expense of other countries.

The main loser here is Jordan, which long enjoyed the status of Guardian of the Holy Places and protector of the Arabs of Jerusalem. Recent years have seen a growing erosion of Jordan’s position in the city, which has been reduced to guardianship of the 0.144 square kilometers of the Temple Mount and no more—as declared by King Abdullah himself. In truth, even on the Temple Mount its status is on the wane and Turkey is plunging into the vacuum, both in the city and on the Temple Mount.

Today, Erdoğan’s Turkey enjoys unprecedented popularity among the residents of Eastern Jerusalem: Turkish flags frequently fly on the roofs of houses in Eastern Jerusalem and even on the Temple Mount. Turkish culture is enjoying a revival, manifested in language classes and the wide presence of Turkish music and foods. The Turks’ public support of the Palestinian cause and adoption of the al-Aqsa issue, and their decision to inject millions of dollars into Eastern Jerusalem, have won them great sympathy and support. The increased Turkish involvement is facilitated by its cooperation with Muslim Brotherhood elements in the city, who frequently serve as their allies and agents.

According to sources in eastern Jerusalem with whom we speak frequently, it is the Turks who fund a great part of the dawa activities in the city—charitable associations, women’s organizations, leisure time and cultural activities, programs for young people, and more. Sheikh Sabri, who has extended his patronage to many of these organizations, has become the figure most closely identified with the Turkish efforts in the city. Many of Turkey’s activities and investments in the city are effected by its long arms—its government assistance agency, the Turkish consulate in Jerusalem, and a string of Turkish organizations that have local branches in Israel or the West Bank.

Alongside the rise of elements identified with the Muslim Brotherhood and of Turkey, we must pay attention to another mounting force in Jerusalem, the Islamic Liberation Party, or, in Arabic, Hizb ut-Tahrir, which has several thousand supporters in the city.

Unlike the Muslim Brotherhood, which endeavors to operate within the existing geopolitical constellation and make its peace with the concept of nation-states, the Liberation Party is a fundamentalist Salafi movement that utterly rejects the idea of nationalism and aims at the establishment of a single Islamic caliphate that operates in strict and exclusive accordance with Shari’a law. Its roots are in Jerusalem, where it was founded in 1953 as an opposition movement to the Hashemite Kingdom and all other Arab regimes with “Western” characteristics that do not enforce Shari’a law. Today the movement has branches all over the world. In recent years, it has been enjoying a new burst of vitality, including in Jerusalem, with the return of the caliphate idea to center stage.

Despite its Jerusalem roots, the Liberation Party is by no means a Palestinian movement. Its supporters in Jerusalem and the West Bank do not define themselves as Palestinians in the national sense of the term and consider “Palestine” to be only one province of the future caliphate. In the Palestinian arena, its members challenge the PA regime and Jordan’s role as the guardian of the holy places, and, rather interestingly, are less concerned with Israeli actions. As they read the map, Israel’s disappearance from Jerusalem and al-Aqsa is only a matter of time; when it comes to pass, they, and not the Palestinian Authority or even the Muslim Brotherhood, will be left in control. In their vision, the global Islamic caliphate will be proclaimed from al-Aqsa.[8]

Like the other Islamic movements, the Liberation Party focuses on dawa with teenagers, women, and children. In addition to its extensive activity on the Temple Mount, its members are to be found in a number of mosques in eastern Jerusalem. Their most conspicuous presence is in the al-Rahman Mosque in Beit Zafafa, where Sheikh Issam Amira is the chief preacher. Amira, who was born and still lives in the village of Sur Baher in the south-eastern quadrant of the city, is without a doubt the movement’s most prominent leader and preacher in eastern Jerusalem and is widely respected as a learned cleric.

In addition to his position in the al-Rahman Mosque, from time to time Amira delivers sermons in al-Aqsa and conducts religion classes in various mosques in the city. In his classes and sermons Amira frequently harps on the culture war raging between Islam and the West. He repeatedly attacks the great powers and accuses them of heresy and contempt for the sacred places of Islam. Nor does he refrain from harsh remarks against Christianity and Christians in general and those in Jerusalem in particular. He lashes into nationalist movements such as Fatah that would like to attract Christians to their ranks instead of treating them as dhimmi.

In addition to preaching and sermons in the mosques, the Liberation Party has acquired growing influence on college campuses throughout the West Bank, to the strong displeasure of the Palestinian Authority, which tries to curb its activities there. In recent years al-Quds University, near Jerusalem, with many students from eastern Jerusalem neighborhoods, has become one of the main arenas of the party’s activity. Its influence is widespread on the social networks, too; a quick search of Facebook uncovers dozens of groups that identify with the party and that have several thousand followers in eastern Jerusalem.

It is important to emphasize that the Liberation Party does not advocate violent jihad. It has always focused on winning hearts for the establishment of the caliphate and not on recruiting armies to do battle against the infidels here and now. Nevertheless, if one listens to the Friday sermons by Sheikh Amira and other preachers identified with the movement, there can be no doubt about the potential influence of their words on young people who are inspired to adopt the path of violent jihad. In other words, even though the party’s leaders propagate the abstract ideas of the establishment of the caliphate and restoration of Shari’a, their orations and Friday sermons accelerate the radicalization of young people in Eastern Jerusalem, with potentially catastrophic results.

Here we must take note of the fine line between the Liberation Party and ISIS, which, it stands to reason, is crossed sometimes. The Liberation Party, as stated, does not advocate violent jihad; on more than one occasion its leaders have expressed their reservations about ISIS and its brutality. Nevertheless, the fact that both are Salafi movements that share the dream of establishing the caliphate may induce supporters of the party to “advance” from a Salafi mindset to a Salafi-jihadist outlook and join the ranks of ISIS.

This may explain the presence of ISIS cells and ISIS operatives in Jerusalem, such as Fadi al-Qunbar, who carried out the terrorist truck-ramming attack in eastern Talpiot in early 2017, and the ISIS cell that was apprehended in the Shuafat refugee camp several months earlier.

The Temple Mount as an Arena of Conflict

Thus far we have considered broad processes that involve most neighborhoods of eastern Jerusalem as well as the Temple Mount. But in order to fully comprehend the Eastern Jerusalem story we must probe more deeply into the situation on the Temple Mount and take a closer look at the interesting dialectic that has emerged between processes in the neighborhoods and those on the Mount.

The first thing to note is that there is a two-way dynamic: events on the Temple Mount constantly affect events in the neighborhoods, while developments in the neighborhoods have repercussions on the Mount. For example, when we mentioned Jordan we observed that it has gradually reduced its historic role in Jerusalem and involvement in political and social processes there, evidently so as to focus its energies on the Temple Mount. This had an immediate and unwanted effect for Jordan: its standing on the Mount, too, was undermined, and various elements began to challenge it. One of the most conspicuous manifestations of this is the fact that many employees of the Jordanian Waqf on the Temple Mount do not always follow orders from Amman and often display loyalty to other players.

Two main currents are currently challenging Jordan on the Temple Mount—elements identified with the Muslim Brotherhood (Hamas, the Islamic Movement, and others) and those affiliated with the Liberation Party. In recent years the former have enjoyed freedom of action on the Temple Mount, chiefly by means of the Murabatun and Murabatat, associations of men and women, respectively, they have deployed there to pump up the story that “al-Aqsa is in danger.” They have also transferred some of their dawa projects there, including summer camps for teens and cultural and leisure time activities for women and children.

The banning of the Islamic Movement will clearly detract from its ability to operate on the Mount, but in all likelihood it will find alternative methods, even if under certain restrictions. The Liberation Party also enjoys freedom of activity on the Mount and its preachers deliver sermons there from time to time. This freedom of action reached its peak in late 2015, when its agents sent hundreds of supporters to the Mount for a vocal demonstration in favor of the caliphate idea, which came off without let or hindrance.

Hence we can see how the growing strength of these two—the Muslim Brotherhood and the Liberation Party—in the neighborhoods of Eastern Jerusalem is catalyzed by their heightened presence on the Temple Mount and at the same time augments this presence.

As we have already hinted, the greatest threat to Jordanian interests on the Temple Mount comes from Turkey. In order to understand the delicate balance that has emerged between the two countries we must go back to the events of May 23, 2015, when a Palestinian crowd interrupted the sermon and prayer service in the Al-Aqsa Mosque led by the chief Qadi of Jordan, Dr. Ahmad al-Halil, and ultimately chased him out with threats and blows.

The significance of this event becomes clear if we go back to a few days earlier, when the president of the Turkish Directorate of Religious Affairs, Prof. Mehmet Görmez, was given a reverential welcome there and listened to with close attention.[9]

None of this takes place in a vacuum. In recent years the Turks have injected significant sums to those who do their bidding on the Temple Mount, for various activities there—Quran-recitation groups, transportation of worshipers to and from the mosque, iftar feasts in Ramadan, renovation and cleaning campaigns, and the like. In general, the Islamist forces on the Temple Mount operate, intentionally or not, to Turkey’s benefit and the detriment of Jordan. They may believe that the replacement of the Jordanian presence by a Turkish presence would be a positive and elcome development.

But Fatah and the Palestinian Authority are not totally absent from the Temple Mount, either, and this seems to be linked precisely to their weakened status in the neighborhoods. Representatives of the PA, who see how rival elements have ensconced themselves on the Mount, are now investing major efforts to shore up their standing there. This often involves confrontations and power struggles with Jordan and an attempt to influence the Waqf officials to come over to their side.

This is the context of the PA’s intensive activity in the international arena, and especially at UNESCO, ostensibly intended to protect the Islamic holy places against an Israeli takeover. This tactic allows the PA to convey to its critics that it is the true defender of al-Aqsa and Jerusalem against the threat of “Judaization,” while at the same time gnawing at Jordan’s historic role as guardian of the Mount. In practice, these steps by the PA may win it a few points in local public opinion, but do not seem to be curbing the growth of its rivals’ power.

Radicalization and Normalization

To sum up what we have written so far: the disintegration of the secular nationalist organizations and institutions in Jerusalem has facilitated the rise of the Islamist factions. This development bears a clear potential for radicalization, especially of young people, which is making itself felt today.

To complete the picture, we must note another trend, essentially in the opposite direction, that to a large extent derives from the same disintegration: normalization of the relations with Israel and even integration into its systems and society.

A thorough analysis of the processes described here leads us to the conclusion that more and more residents of eastern Jerusalem, who despair that the Palestinian national establishment in Jerusalem will ever be able to better their status and situation, are choosing to rely on themselves and adopting a much more pragmatic policy than in the past.

The fact that no alternative to Israeli control of the city is visible on the horizon also contributes to this decision. If once upon a time the offices of the National Insurance Agency and Interior Ministry were the exclusive venues of interaction between the residents of Eastern Jerusalem and the Israeli establishment, today there are many more arenas that reflect Eastern Jerusalemites’ rapid integration into the Israeli system.

These processes do not emerge from a vacuum. To judge by the last Washington Institute survey among residents of eastern Jerusalem, conducted in June 2015, when a peace accord is reached, 52% of them would prefer to become citizens of Israel, whereas only 42% would want to be citizens of the Palestinian state. These figures reflect the continuation and even intensification of a trend that began some years ago. A similar poll conducted in 2010 found that only 33% would prefer Israeli citizenship; by 2011 the figure had risen to 40%. The respondents cited a series of pragmatic reasons for their preference, including the higher incomes in Israel, its advanced medical services, social benefits, and freedom of movement.[10]

The most striking datum in this context, expressing the strong desire to remain under Israeli sovereignty in any future scenario, is the vast increase in the numbers of Eastern Jerusalemites filing applications for Israeli citizenship.[11] In 2016, more than a thousand of them submitted naturalization requests to the Interior Ministry, whereas only a few dozen had done so in 2003. Another indicator is provided by the many forums and programs to learn Hebrew that have been established in Eastern Jerusalem in recent years. The younger generation, perhaps unlike their parents, wishes to master Hebrew and employ the language to acquire advanced education and obtain better jobs.

These are evidently the considerations behind eastern Jerusalem parents’ mounting preference to send their children to schools that follow the Israeli curriculum. A recent survey conducted by the Jerusalem Municipality found that almost 48% of parents whose children are studying for the Palestinian matriculation exams would like to find an alternative.

The alternative in greatest demand is the Israeli matriculation exams. Today we are witnessing a significant increase in the number of Eastern Jerusalem teens who take the Israeli exams. Over the last decade the number of pupils attending high schools that follow the Israeli curriculum has increased by an order of magnitude, from a few hundred to almost 5,000.

Similarly, many more students from Eastern Jerusalem are enrolled in Israeli academic institutions than in the past. Demand is soaring for the pre-university preparatory programs in Eastern Jerusalem, most of them subsidized by the Israeli government. The colleges in the western part of the city, such as Hadassah and Azrieli, are also increasingly popular.

With regard to business activities and employment, too, we are seeing an unprecedented trend. The hi-tech incubator recently established in the eastern part of the city has already attracted its first projects in the fields of software and biomedicine. The employment center that opened in the Shuafat neighborhood in 2015, with Israeli government funding, has already processed more than 2,000 clients through its vocational training programs, courses, and workshops. Almost 40% of them were placed in jobs, in both the eastern and western parts of the city.

The rise in the number of Eastern Jerusalemites with higher education is producing a slow but steady advance from low-status jobs to services and sales, healthcare, and so on. There are also signs that Eastern Jerusalemites are penetrating more senior positions in industry and construction. It is quite possible that in the near future we will see an explosion in the number of liberal professionals from Eastern Jerusalem, such as attorneys, physicians, and accountants—jobs that traditionally were held only by Israeli Arabs in Jerusalem.[12]

As things appear from our perch in Jerusalem City Hall, eastern Jerusalemites are evincing an extraordinary tendency to recognize and deal with the municipality and its institutions. The municipality is no longer perceived merely as the greedy collector of property and other taxes, but also as an agency that provides rights and services. We are in constant dialogue with the community administrations of Eastern Jerusalem neighborhoods, which cooperate fully with the municipality to improve the residents’ quality of life.

A new community administration was recently established for Abu Tor and Silwan, and the first fruits of its labors are already visible. In addition to the community administrations, an increasing number of parents’ committees in Eastern Jerusalem eschew political identification with Fatah or Hamas and take an independent and businesslike attitude in their contacts with City Hall and its agencies. Unlike the politicized parents’ committees, they are not afraid to express their interest in the introduction of the Israeli curriculum to their children’s schools.

In our eyes, even the protest demonstrations by eastern Jerusalemites in Safra Square, in front of City Hall, are not nuisances, but rather a welcome phenomenon that expresses their de facto recognition that the municipality is the appropriate address for solving their problems.

In summary, having dealt at length with the growing trends of Islamization and radicalization, and offered a brief account of the fruits of normalization and eastern Jerusalemites’ integration into the Israeli scene, we now ask what it means to be a Muqdasi (Jerusalemite) today.

On the surface, there is a jumble of different and divergent orientations that are incompatible. Despite the obvious inner contradiction, our impression is that many eastern Jerusalemites somehow manage to move in both directions at the same time. Nevertheless, we believe that one of them may eventually win out over the other.

The Muslim Brotherhood ideology and Salafi doctrines may be translated into more intense opposition to the Israeli presence in Jerusalem, leading to the eruption of new waves of violence even more severe than those of the past. Or the coming years may see an increased number of eastern Jerusalemites among the graduates of the Hebrew University and on the staff of the Hadassah Hospitals. These people, we believe, will stand in the forefront of a large and pragmatic camp of eastern Jerusalemites who want to penetrate key posts in the city and spearhead a process of integration.

Summary and Policy Recommendations

The deep processes we have described here pose a series of challenges, opportunities, and dilemmas for the Israeli government.

The enlarged foreign presence in the heart of Israel’s capital, described above at length, touches the deepest chords of the issue of Israeli sovereignty in the eastern part of the city.

On the surface, those who believe that Israel should not impose its sovereignty might welcome this development. However, they must also take account of the security implications of the murderous anti-Jewish ideology that some agents of this presence are instilling in the 350,000 Palestinians who live alongside 550,000 Jews.

On the other side, those who condemn the foreign presence because it undermines Israeli sovereignty and has grave security implications must be aware that efforts to eliminate this presence, whether by the security forces or through diplomatic channels, are not enough. Some of these foreign organizations provide services that the residents require; their expulsion would require Israel to fill the void, and this would major budgetary repercussions.

This foreign activity intensifies the battle raging between the Israeli side and the Islamic Arab side for the minds and hearts of individuals and society in Eastern Jerusalem. For Israel to chalk up points it must not just weaken the other side but also beef up its provision of services in eastern Jerusalem and brand itself as a positive force that is concerned for the residents’ well-being.

The mobilization of the national and municipal governments in recent years to improve the quality of services and infrastructure in eastern Jerusalem has planted important seeds of progress, but continued advances in this direction will require the investment of significantly larger budgetary resources.

It should be noted that the Jerusalem municipality is making a major effort to reduce the disparities and improve the level of services and infrastructure in Arab neighborhoods, with an emphasis on roads (more than NIS 50 million a year) and classrooms (NIS 500 million over the coming decade).

Turning our attention to the domestic Israeli scene, we find two overarching alternatives proposed in the discourse about the issue. There are two main paradigms about eastern Jerusalem. The first advocates keeping the city united; the second calls for its re-division, with the eastern sector serving as the capital of the Palestinian state. The latter paradigm views partition of the city as part of a political process that would include territorial compromise by both Israelis and Palestinians.

Two new plans for partition of the city have been floated recently. The first, promoted by former minister and MK Haim Ramon, calls for a unilateral Israeli pullback from the Arab neighborhoods, similar to the Gaza disengagement, and the construction of a wall between the two parts of the city. The second plan, which enjoys the support of various Palestinian elements, would establish a Palestinian municipality to manage the affairs of the Arab neighborhoods, alongside the Jewish municipality that oversees the Jewish neighborhoods, but would not create a physical barrier between the two parts of the city. A joint committee or agency would coordinate between the two city halls, in conjunction with Israel and the Palestinian Authority.

When considering these alternatives for eastern Jerusalem, we must begin by acknowledging the physical proximity and strong links between the Jewish and Arab populations of the city and be aware of the shared routine of daily life in domains such as transportation, employment, healthcare, and shopping.

A look at the map of the city makes plain that the Arab and Jewish neighborhoods are interlocked and sometimes only a few meters apart. What is more, in some neighborhoods Jews and Arabs live in adjacent or even the same buildings, whether for ideological reasons (Jews) or to improve their quality of life (Arabs). The daily interchanges between the two groups have been facilitated by the road and public transportation networks that link Arab and Jewish neighborhoods. The best example of this is the light rail system, which has been subjected to a hail of stones by Palestinian rioters precisely because it is a symbol of the unity of the city.

The demographic and geographical layout of the Jewish and Arab neighborhoods, along with the transportation network, makes the erection of an actual barrier between the two groups unfeasible or even impossible. This difficulty is what seems to have led to the idea of a Palestinian municipality to operate alongside the Israeli one.

We believe that the strongest opposition to this proposal will be voiced by the Palestinian residents themselves. They see the Palestinian Authority as a corrupt and failed regime that has no commitment to provide services to citizens. Hence implementation of this plan might lead to an outflux of Palestinians to the Jewish neighborhoods that come under the jurisdiction of the Jewish municipality, creating housing pressure and a burden on the Jewish neighborhoods and their infrastructure.

The other plan for partition of the city mentioned above, the mirror image of the previous one, calls for a unilateral Israeli disengagement from the Arab neighborhoods and the construction of a physical barrier between them. Haim Ramon recently founded the ‘Movement to Save Jewish Jerusalem’ to promote this idea.

The main points of its platform are as follows:

- Most of the villages incorporated into Jerusalem in 1967 would be de-annexed.

- A continuous security fence would be erected without delay between the Palestinian villages and Jerusalem proper, to separate the Jewish neighborhoods from the Palestinian districts.

- The IDF and other Israeli security forces would continue to operate in the de-annexed villages.

- The situation in the rest of the eastern part of the city—the Old City, the Holy Basin, and the Jewish neighborhoods—would remain as at present.

- Some 200,000 Palestinians would thus be removed from the municipal boundaries of Jerusalem, leaving the city with a Jewish population exceeding 80%.

- The permanent-resident status of these 200,000 Palestinians would be revoked, removing the economic burden that the villages have been posing on Israel.

- The Knesset would enact the required legislation, and first and foremost an amendment to the Basic Law: Jerusalem the Capital of Israel.

We believe that this idea has fatal flaws that vitiate it for Israel. On the security front, there is the risk of handing over territories to the Palestinians without coordination of the transfer, with the inevitable boost to the strength of terrorist organizations and dissident Palestinian Authority elements. Building a barrier through Jerusalem would repeat the experience of the previous decade, which made life very difficult in the Shuafat refugee camp and Kafr Aqub and affected security in the nearby Jewish neighborhoods, especially Pisgat Zev.

From the political perspective, this plan’s Achilles’ heel is that it totally ignores the role and character of the Palestinian actor that would control the neighborhoods on the eastern side of the barrier. A stronger Hamas on the eastern Jerusalem street might gradually gain control of these villages, with all this implies from a security and political standpoint. Because the change would not be carried out in coordination and negotiations with it and because Israel would retain control of the Holy Basin, the Palestinian Authority, for its part, would oppose this plan and could be expected to stir up chaos on the ground.

Partition of the city following the “classic” route, as part of a political accord, strikes us as the least likely scenario of all, given the current state of relations between the Israeli and Palestinian sides and low level of trust and communication that prevails.

Many research studies and position papers written over the years have proposed various ideas for a partition of this sort that might be feasible, with the accompanying advantages and disadvantages of each plan. The main contribution of the present authors’ “field smarts” to the analysis of this alternative is our close acquaintance with the leaders and worldviews of the Palestinian nationalist groups active there. This leads us to believe that in any form of partition of the city, Israel must be concerned not only about the terrorist infrastructure that would emerge only a few meters from Jewish neighborhoods, but also about the currents that would dominate the educational, cultural, and welfare systems of the Palestinian political entity established. Children would be brought up with a deeply rooted hatred of Israelis, glorification of the violent struggle against it, and rejection of Israel’s existence as a Jewish state.

The essential flaws we have identified in the various proposals for redividing the city make the need for a deep analysis of the current situation of the united city more acute, since we may assume that, given the current political constellation on the Israeli and Palestinian sides, it will continue for many years.

Life in a shared city with no barriers between the two groups creates a real security challenge, especially in periods of religious and political tensions, as exemplified by the knife intifada, a challenge that the Jerusalem police managed to overcome. The experience of recent years has shown that success on this front requires not only ingenuity by the security agencies but also the enlistment of all civilian elements in the effort.

The intimate dialogue based on two-way trust with Arab leaders in the fields of education, business, and community life, in normal times as well as during crises, proved to be invaluable for moderating the violent friction between the two sides. Methods taken from education, such as lengthening the school day and keeping children and teens inside a protecting and supportive educational environment, are another proven way to lower the level of violence.

Finally, the online world of the social networks, which played a major role in triggering the violence, also turned out to be a place where positive actions (such as the distributing updates and messages from the mayor on Facebook in Arabic) and the refutation of disinformation about the Temple Mount can curb and counter the incitement propagated by many websites.

An analysis of the civic aspect of the paradigm of the united city as it exists today, along with adoption of a sincere and focused attitude that recognizes both sides’ sensitivities, suggests that the experience of unity is imperfect for the Palestinian residents of Jerusalem. Constantly exposed to the immensity of the gulf between the two sides of the city and the disparate living standards of the two population groups, they feel alienated from the Jewish sector and its institutions.

In recent years there has been a quantum reduction in these gaps and an improvement in the Arab residents’ standard of living in many domains, including education, social services, roads, and leisure time activities; but the gap remains vast and closing it would require another major increase in government investment in eastern Jerusalem. Here the exclusion of eastern Jerusalem from the substantial budget allocations of the five-year plan for the Arab sector in Israel—even though eastern Jerusalemites constitute 20% of all the Arabs under Israeli jurisdiction—cries out for attention.

Drawing on this analysis, we believe that Israel should take steps to infuse additional and more significant content than at present in the factors that work to unite the city, by means of actions that increase the Eastern Jerusalem Arabs’ sense of belonging to the city and the state.

On the basis of the hundreds of conversations we have had as part of our job with dozens of prominent figures, both women and men, we believe that broad sectors of the Palestinian population have come around to a pragmatic attitude about the Israeli authorities, despite their Palestinian national identity, and see Israel not only as the culprit to be blamed for their difficult situation as individuals in the community but also as the only possible source for solving their problems and turning their lives around.

Infusing content into the united city, as we advocate, is not simply a matter of increasing government budgets for the development of the Arab neighborhoods of Jerusalem. It also means adopting a more innovative line of thought and action in deeper content worlds that relate to the circles of identity of the Palestinians in Eastern Jerusalem.

Simplifying and shortening the naturalization process for Palestinian residents of Jerusalem, along with increased access to Israeli matriculation tracks and Israeli institutions of higher education, could not only alleviate their sense of frustration and alienation but also encourage a sense of belonging. There are many Palestinians in eastern Jerusalem who have reached the instrumental level of exploiting the advantages offered by the western half of the city and would now like to participate in Israeli society at a deeper level, learning from it, mingling with it, and even joining it, as manifested in the growing number of eastern Jerusalem teenagers who are doing civilian service after high school.

Encouragement of this trend has strategic implications not only for the unity of the city but also for the mid- and long-term security perspective. In another decade or two, the teenagers who engage more deeply with Israeli society today will be the moderates and pragmatists who restrain Palestinian society in normal times as well as periods of crisis.

During the recent spate of violence, teachers and principals went out into the streets to get their pupils to curb their emotions and avoid attacking innocent persons, both Arabs and Jews. In another decade, perhaps these teachers will be joined by merchants, businesspeople, community activists, and cultural figures who endeavor to introduce mutual respect and sensitivity to the turbulent reality of Jerusalem.

[1] Said, Edward W. The Question of Palestine, University of Michigan: Times Books, 1979, p. 122.

[2] A recent Israeli High Court ruling from March 2017 has ordered the Interior Ministry to restore the residency rights of a Palestinian man born in Jerusalem that was absent from the city for more than 7 years. This precedent-setting ruling challenges the practice that treated Eastern Jerusalemites like immigrants in their own city, by recognizing them as ‘Native-born Residents’. Nevertheless, it is still early to estimate the full implications of this ruling.

[3] Hillel Cohen, “The Rise and Fall of Jerusalem as the Capital of Palestine,” in Ora Ahimeir and Yaakov Bar-Siman Tov, eds., 40 Years in Jerusalem, 1967–2007 (Jerusalem: Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies, 2009), p. 105 (Hebrew).

[4] Ibid., p. 104.

[5] Pinhas Inbari, “Religion and Politics in Eastern Jerusalem” (Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, 2016, p. 9); at http://jcpa.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Inbari_Religion_Politics_Eastern_Jerusalem.pdf(Hebrew).

[6] This came up in our talks with actors on the ground.

[7] Washington Institute Survey, 2015, at https://trello.com/c/piLxIDA4/14-http-www-washingtoninstitute-org-policy-analysis-view-half-of-jerusalems-palestinians-would-prefer-israeli-to-palestinian-citize.

[8] Inbari, “Religion and Politics,” p. 5.

[9] Ibid., p. 7.

[10] Washington Institute Survey, 2015.

[11] Nir Hasson, Ha’aretz, Jan. 12, 2017; at http://www.haaretz.co.il/.premium-1.3231311?=&ts=_1484204657751.

[12] Merrick Stern, “Employment Integration in a Volatile Situation” (Jerusalem: Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies, 2015), pp. 68–45; at http://jerusaleminstitute.org.il/.upload/%20%D7%AA%D7%A2%D7%A1%D7%95%D7%A7%D7%AA%D7%99.compressed.pdf(Hebrew).

https://hashiloach.org.il/residents-eastern-jerusalem-historic-crossroads/