27.04.23

Editorial Note

On May 3, the Institute for Holocaust, Genocide, and Memory Studies [IHGMS] at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, is holding a conference, “Encounters” Aftermaths annual series, on Zoom, together with the Avraham Harman Research Institute of Contemporary Jewry at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. In the event, a conversation with Adel Manna will take place, on his 2022 book, Nakba and Survival: The Story of Palestinians Who Remained in Haifa and the Galilee, 1948-1956. The event is organized by Prof. Alon Confino, the Director of IHGMS, and Prof. Amos Goldberg, the Jonah M. Machover Chair in Holocaust Studies at the Department of Jewish History and Contemporary Jewry and the Head of the Avraham Harman Research Institute of Contemporary Jewry, at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Dr. Adel Manna is a Palestinian specializing in the history of Palestine during the Ottoman period and Palestine in the 20th century. He has taught at The Hebrew University and Bir Zeit University since the early 1980’s. He is currently a senior research fellow at the Jerusalem Van Leer Institute.

Manna would hold the conversation with Amos Goldberg.

In his book Nakba and Survival, Manna “tells the story of the Palestinians in Haifa and Galilee during, and in the decade after, mass dispossession. Manna uses oral histories, diaries, memoirs, and archival sources to reconstruct the social history of the Palestinians who remained and returned to become Israeli citizens. Manna shows in his path-breaking book that remaining in Israel in the aftermath of the Nakba under the Israeli military government were acts of resilience in their own right.”

What Manna neglects to inform his readers is that less than a decade before the “Nakba,” the Palestinians, under the influence of Nazi Germany, were rioting against the British and the Jews.

A new book by Oren Kessler discusses the 1936-39 riots. A book review published last month states: “Describing the situation in 1936, just prior to the Great Revolt, Kessler reminds us that Hitler and the Nazis had been in power in Germany for three years, and that his intention to emasculate his Jewish population was already evident. In Palestine, the fanatical Izz al-Din al-Qassam, killed by the British police, had become the first Arab martyr and cult hero. Meanwhile, Jewish immigrants had been flooding into Palestine. By 1936 there were some 400,000. As Kessler puts it: ‘The Arabs of Palestine started to wonder…whether a world war was looming, one that might rid their country of Britain and the Jews for good.'”

Dina Porat, Professor Emeritus of Modern Jewish History at the Department of Jewish History, Head of the Kantor Center for the Study of Contemporary European Jewry, and holds the Alfred P. Slaner Chair for the Study of Contemporary Antisemitism and Racism at Tel Aviv University, who, since 2011 served as Chief Historian of Yad Vashem, is an expert on the Holocaust. According to Porat, the Palestinian leader, Mufti Haj Amin al-Husseini, “was no lover of the Jewish people. He was an ardent antisemite… [He] had a specific agenda in meeting Hitler in 1941. The Protocol from this fateful meeting specifically states that ‘The Fuehrer replied that Germany stood for uncompromising war against the Jews and that naturally included active opposition to the Jewish national home in Palestine.’ Hitler promised that he would carry on the battle to the total destruction of the ‘Judeo-Communistic Empire’ in Europe.”

Moreover, in 1946, the American Christian Palestine Committee published its 50 pages report titled “The Arab war effort, a documented account.” The report details the Palestinian Arabs, including the Mufti, liaising with Nazi Germany.

At the very least, this evidence implies that the Palestinians had hopes that a Mediterranean-style Final Solution would solve their “Jewish Problem.” After the defeat of the Nazis, the Palestinian leadership put their faith in the Arab countries to wipe out Israel from the map. Needless to say, this mindset prevented them from accepting the 1947 UN Partition proposal.

Manna, like many Palestinian and pro-Palestinian historians, tries to hide the nexus between the Nazis and the Palestinians. As a result, not enough research has been conducted on this topic.

What is most troubling is the position of Goldberg, the chair of Holocaust Studies, who emerged as a major voice for those who push to equate the Holocaust with the Nakba – a fact IAM emphasized before. Goldberg was hired to teach and research the Holocaust, not to propagate his political agenda at the expense of the Israeli taxpayers.

Palestine 1936 is essentially the story of how two nationalist movements took root and developed, leading to the Great Arab Revolt and the start of today’s Arab-Israeli conflict.

Palestine 1936: The Great Revolt and the Roots of the Middle East Conflict is an eminently readable account of how the State of Israel emerged from the flames of Mandate Palestine, but it is much more. It is the first scholarly, extensively researched, investigation into the formative events of 1936-39 in the Holy Land – events that its author, Oren Kessler, demonstrates to be the origin and model for the subsequent unresolved, and perhaps unresolvable, Arab-Israel conflict. He shows how, during what he calls “the Great Revolt,” the concept of Arab Palestinianism was born while, at the same time, the decades-long Zionist dream of a Jewish state – Jewish nationalism – began to solidify into reality.

The Arab Revolt of 1936–39 was the first sustained uprising of Palestinian Arabs in more than a century. Thousands of Arabs from all classes were mobilized, and nationalistic ideas were disseminated throughout Arab society. The British, mandated to govern Palestine and create a national home for the Jewish people, were taken aback by the extent and intensity of the revolt. They shipped more than 20,000 troops into Palestine, and by 1939 the Zionists had armed more than 15,000 Jews in their own nationalist movement.

Dealing with the period leading up to 1936, Kessler describes the short, but deadly, pre-Mandate attacks on Jews – 1920 in the Old City of Jerusalem, and May Day 1921 in Jaffa – but he categorizes much of the later 1920s as “the Mandate’s calmest chapter.” The number of Jewish immigrants reached 80,000; agricultural settlements doubled to over 100; the Hebrew University was founded; and it was a time of economic and trade growth and development.

But it was the calm before the storm. In 1929, Tisha Be’av (the 9th of Av) – the day both First and Second Temples in Jerusalem were destroyed – marked the start of the deadliest clash so far between Jews and Arabs. British officialdom had promulgated new severe restrictions on Jewish access to the Western Wall. Mass protests by Jews generated counter protests by Arabs. The clashes between them got out of hand. Bloodthirsty Arab mobs embarked on a six-day killing spree which included lynching, rape and other unspeakable brutality. In addition to hundreds of wounded on both sides, 133 Jews died.

Britain set up a commission of inquiry. Its report, in the spring of 1930, concluded: “The outbreak…was from the beginning an attack by Arabs on Jews.”

“The outbreak…was from the beginning an attack by Arabs on Jews.”

Describing the situation in 1936, just prior to the Great Revolt, Kessler reminds us that Hitler and the Nazis had been in power in Germany for three years, and that his intention to emasculate his Jewish population was already evident. In Palestine, the fanatical Izz al-Din al-Qassam, killed by the British police, had become the first Arab martyr and cult hero. Meanwhile, Jewish immigrants had been flooding into Palestine. By 1936 there were some 400,000. As Kessler puts it: “The Arabs of Palestine started to wonder…whether a world war was looming, one that might rid their country of Britain and the Jews for good.”

The incident that sparked the Great Revolt occurred on April 15, 1936. A Jewish poultry dealer, ambushed by Arabs seeking money for weapons intended to avenge the death of Qassam, could not meet their demands and was shot. Kessler recounts, with the pin-point accuracy only achieved through assiduous research, the details, one after another, that built up to a full-scale riot in Jaffa, known as the Bloody Day, while the British police attempted, and failed, to control the situation.

Shortly afterwards, an Arab National Committee was formed in Nablus, to be followed by local branches across the country, all urging the Arab public to withhold their taxes. Then came the establishment of an Arab Higher Committee (AHC), chaired by the mufti of Jerusalem, Hajj Amin al-Husseini, a visceral hater of the Jewish people. The AHC masterminded a general strike of Arab workers, demanding an end to Jewish immigration, an end of land sales by Arabs to Jews, and the establishment of a representative government to reflect the country’s Arab majority.

The Arabs’ anti-British action continued for months, with waves of armed rebellion, arson, bombings, and assassinations. Masterminded by the mufti, British soldiers and Jewish civilians were slaughtered indiscriminately, to say nothing of suspected Arab collaborators. In desperation, the government agreed to a step it had previously resisted – arming and training Jews for self-defense. The Jewish Supernumerary Police was founded.

Kessler describes how the mufti, alarmed at the effect the revolt was having on the Arab economy, maneuvered his way out of the uprising. The strike was called off in October and, with peace restored, Britain reverted to its time-honored device of a royal commission of inquiry.

Presided over by Lord Robert Peel, the commission was dispatched to investigate the volatile situation. The mufti, Hajj Amin, sent them a brief letter of welcome “to this holy Arab land” but declined to appear before them, given Britain’s efforts to “Judaize…this purely Arab country.”

Its star witness, Kessler tells us, was Chaim Weizmann, head of the World Zionist Organization. During the Peel Commission’s two months in Palestine, he testified five times. In July 1937, the commission reported. In their view, the revolt was caused by an Arab desire for independence and the fear of the Jewish national home. They declared the Mandate unworkable and also that separate undertakings given by Britain to the Arabs and the Jews were irreconcilable. Consequently, the commission recommended that the region be partitioned. For the first time, a British official body explicitly spoke of a Jewish state. The Arabs, horrified by the commission’s conclusions, increased the ferocity of the revolt during 1937 and 1938.

Kessler charts how a change of direction within the British government led to the London conference of 1939, where the concept of limiting permitted Jewish immigration to Palestine and restrictions on Jewish land purchase surfaced. These concepts were later embodied in what is known in British parliamentary terms as a White Paper (the precursor to legislative action by the government), which was rejected by Arabs as inadequate and by Jews as oppressive. The Zionist opposition led to violent anti-government protests in Palestine and a flood of illegal immigration.

In an Epilogue, Kessler sketches the trajectory of the post-Second World War Arab-Israeli conflict. Its roots in the events of 1936-39 are obvious.

One Arab figure features prominently throughout the book. Musa Alami was the very opposite of extremist in temperament. The son of a one-time mayor of Jerusalem, he was probably the first Arab from Palestine to attend Cambridge University, which he did in the years following WW I. Mature and generous in disposition, he studied law but read widely in philosophy. He is also known to have read History of Zionism by Nahum Sokolov, a future head of the Zionist Congress.

It was after the 1929 riots that David Ben-Gurion first met Musa Alami. He described him as “a nationalist and a man not to be bought by money or by office, but who was not a Jew-hater either.” He was, Ben-Gurion wrote, “extraordinarily intelligent,” judicious and trustworthy. Their discussions in the early 1930s were Ben-Gurion’s first attempt to find common ground with the Arabs of Palestine.

The two men maintained a life-long relationship. After the Six Day War, Ben-Gurion phoned him in London, urging him to return to the Middle East to help make a viable peace out of Israel’s extraordinary victory, but this was a step too far for Alami. Two years later, they met in London and, according to Alami, Ben-Gurion discussed how Israel’s territorial gains might be used to achieve a permanent accord between Israel and the Arab world: In return for peace, said Ben-Gurion, Israel should relinquish all the territories conquered in 1967, with the exception of Jerusalem and the Golan Heights.

According to Kessler, Ben-Gurion reported these discussion to the Foreign Ministry, but it is unclear whether any attention was paid to them. By then, Ben-Gurion was near the end of his active career. He died in 1973. His friend Musa Alami passed away in 1984.

Palestine 1936 is essentially the story of how two nationalist movements took root and developed. Oren Kessler tells us that he is no academic. He is, though, an accomplished journalist who, some years ago, became fascinated by the then under-recorded history of the Great Arab Revolt of 1936-39 and decided to research and write about it. The extent and depth of his research is evidenced in the 49 pages of references that he includes in his work. But it is his journalistic skills that make the book so absorbing a read for everyone – scholar and general public alike. This detailed account of a seminal period in the history of both Israel and the Arab world is highly recommended. ■

The writer is the Middle East correspondent for Eurasia Review. Follow him at: www.a-mid-east-journal.blogspot.com

Palestine 1936: The Great Revolt and the Roots of the Middle East Conflict Oren Kessler Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2023 334 pages, $26.95 orenkessler.com

EVENT: [IHGMS] “Encounters”: A conversation with Adel Manna on his book “Nakba and Survival: The Story of Palestinians Who Remained in Haifa and the Galilee, 1948-1956” (University of California Press, 2022) via ZOOM Webinar (May 3)

[The Institute for Holocaust, Genocide, and Memory Studies at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and the Avraham Harman Research Institute of Contemporary Jewry at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem present their “Encounters” annual series: Aftermaths]

In Nakba and Survival, Adel Manna tells the story of the Palestinians in Haifa and Galilee during, and in the decade after, mass dispossession. Manna uses oral histories, diaries, memoirs, and archival sources to reconstruct the social history of the Palestinians who remained and returned to become Israeli citizens. Manna shows in his path-breaking book that remaining in Israel in the aftermath of the Nakba under the Israeli military government were acts of resilience in their own right. In conversation with Manna will be Amos Goldberg.

Dr. Adel Manna is a Palestinian historian specializing in history of Palestine during the Ottoman period and Palestine in the 20th century. He has taught since the early 1980’s at The Hebrew University and Bir Zeit University. Currently, he is a senior research fellow at the Jerusalem Van Leer Institute.

Prof. Amos Goldberg is the Jonah M. Machover Chair in Holocaust Studies at the Department of Jewish History and Contemporary Jewry and the Head of the Avraham Harman Research Institute of Contemporary Jewry, at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Register in advance for this event here: https://umass-amherst.zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_OS_fY112QVCEA8jtmVtY7g#/registration

======================================

https://www.yadvashem.org/blog/setting-the-record-straight.html

Setting the Record Straight

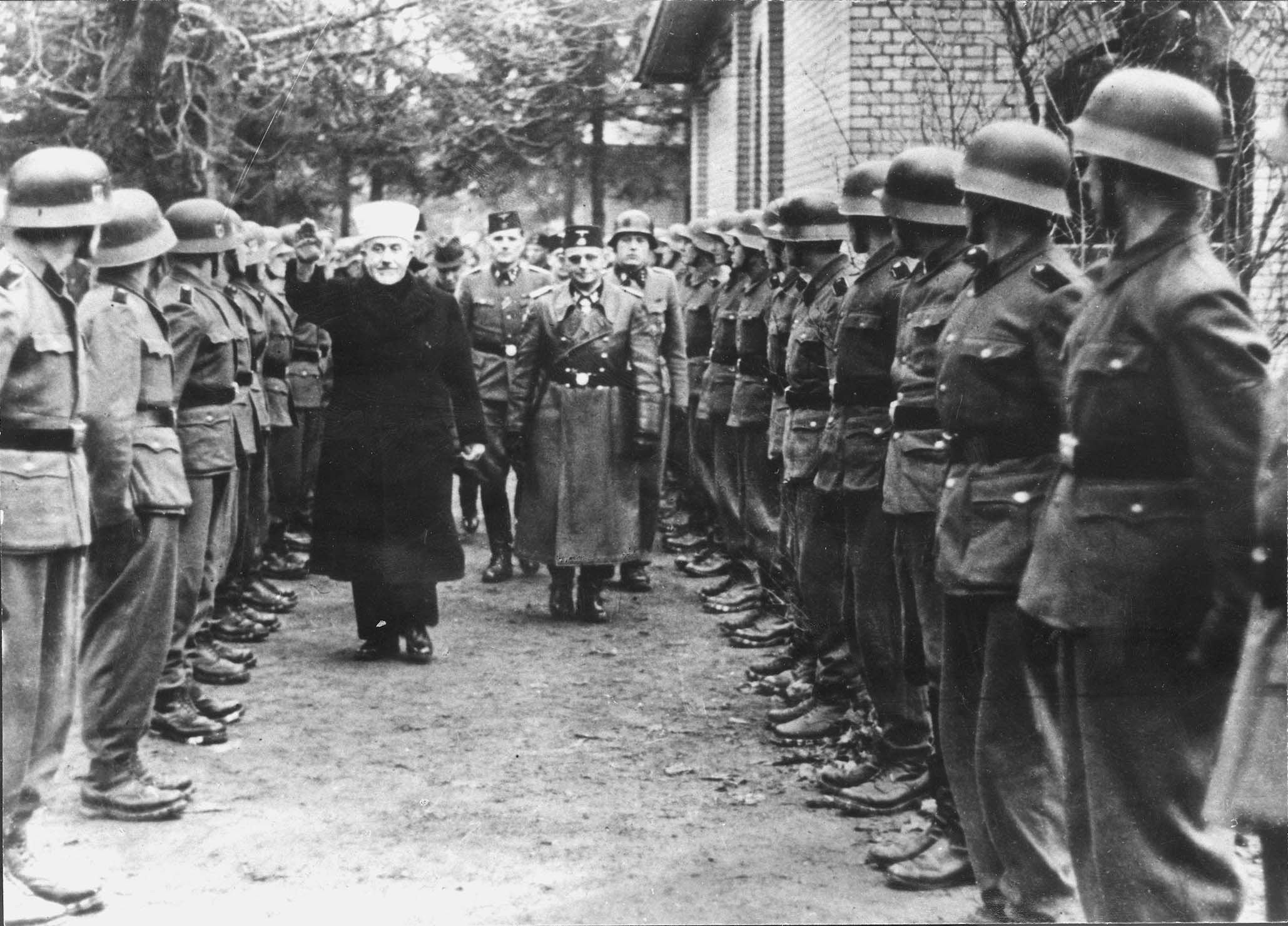

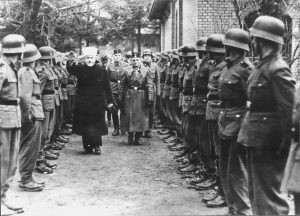

Bosnia and Herzegovina, Haj Amin al-Husseini, the Mufti of Jerusalem, reviewing a unit of Muslim Bosnians in the service of the Nazis

It is a well-documented and undisputable fact that many years before his rise to power, Adolf Hitler was already obsessed by the notion that the Jews constituted an existential danger to the humankind, and thus world Jewry needed to be eliminated at all costs.

This ideology began to be formed by Hilter when he was a solider during World War I. Hitler believed that the war had not only been caused by the Jews, but also that the Jews had stabbed Germany in the back. Hitler went on to develop his obsession with the Jewish problem in his infamous manifest, Mein Kampf, and later in other central documents of the Nazi Party that began to establish itself in the 1920s. Finally, in a speech at the Reichstag on January 30, 1939, Hitler stated outright that if world Jewry would ‘once again drag the entire world into a World War’ then the only possible outcome would be the extermination of the Jewish people.

All of these facts clearly show that Adolf Hitler was determined to annihilate the Jews, and subsequent historical events demonstrate how this mania developed them into official Nazi policies. Hitler didn’t need anyone else, including the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Amin al-Husseni, to come up with the idea to implement the “Final Solution.”

The Grand Mufti’s visit, over two years after the outbreak of WWII, came once many “Final Solution policies were already in full swing. Almost immediately following the invasion of Poland in September 1939, Reinhard Heydrich received instructions from Berlin giving the orders to establish ghettos and Jewish Councils in the occupied Polish territories. It was widely understood amongst the SS that the ghettoization process of the Jews in Europe was a stepping stone for the implementation of the “Final Solution.” In addition, after the invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 the SS Einsatzgruppen began the mass murders of the 1.5 million Jews in Lithuania, Russia, and the Ukraine. The first extermination camp, Chelmno, began operations at the beginning of December 1941 just days after the meeting with the Grand Mufti. The building of the death camp had already been underway for several months when these two leaders met.

The Mufti had a specific agenda in meeting Hitler in 1941. The Protocol from this fateful meeting specifically states that “The Fuehrer replied that Germany stood for uncompromising war against the Jews and that naturally included active opposition to the Jewish national home in Palestine.” Hitler promised that he would carry on the battle to the total destruction of the “Judeo-Communistic Empire” in Europe. The Mufti of Jerusalem was no lover of the Jewish people. He was an ardent antisemite, but the idea of the “Final Solution” was Hitler’s alone, as was the implementation of its appalling policies and actions.

Posted by Prof. Dina Porat

Dina Porat is Professor Emeritus of Modern Jewish History at the Department of Jewish History, Head of the Kantor Center for the Study of Contemporary European Jewry, and holds the Alfred P. Slaner Chair for the Study of Contemporary Antisemitism and Racism at Tel Aviv University. Since 2011 she has served as Chief Historian of Yad Vashem.