Shuhada Street is a half-mile long road in the Palestinian city of Hebron in Israel’s West Bank. It was once the thriving market center of the city, frequented by Palestinians and Israelis daily. Today, it is a virtual ghost town, largely shut down by the Israeli military for security reasons. It has become central to the Palestinian narrative and the symbol of an alleged Israeli apartheid that underlies the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement against the State of Israel.

Why Shuhada Street was closed, how the commercial center of Hebron has moved less than a mile from the now abandoned Shuhada Street and become a thriving market district seldom if ever visited by outsiders, and a place where Jews (not just Israelis, but Jews from any country) are banned is a story seldom told in full. It represents the true story of “apartheid” in Hebron. I visited the city last week and expose the myth of Shuhada Street for the first time here.

The Jewish connection to Hebron dates back almost 4,000 years to when Abraham, the father of Judaism, came to the Land of Israel and settled in the city. Abraham purchased a plot of land, known as the Cave of the Patriarchs, as a burial plot. The site is considered to be the final resting place of Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebecca, Jacob and Leah, the Patriarchs and Matriarchs of the Jewish religion. It is also said that King David was anointed king in Hebron, and that Hebron was the first capital of Israel until it was moved to Jerusalem.

As a result of this historic significance, Jews have prayed in Hebron since biblical times, and with a few interruptions have lived there continuously. Hebron is considered to be the second holiest city for Jews after Jerusalem.

Hebron has a long and complicated history, having been conquered by many invading peoples, including the Babylonians, Romans, Byzantines, Muslim Arabs, Crusaders, Ottomans, Mamelukes and the British. Following the creation of the State of Israel in 1948, Hebron was captured and occupied by the Jordanian Arab Legion. During the Jordanian occupation, which lasted for 20 years, until 1967, Jews were not permitted to live in the city, nor to visit or pray at the Jewish holy sites in the city. No one complained of “apartheid.”

After being attacked by Jordan during the Six Day War in 1967, the Israelis captured Hebron and reopened the city to Jews and peoples of all religions. Starting in 1968, a small group of Jewish settlers attempted to create a community near the Cave of the Patriarchs.

They were met with violence. In 1968, a 17-year-old Palestinian threw a grenade at Jews praying at the tomb, wounding 47, among them an 8-month-old child. A deadly terrorist attack occurred in May 1980 in which six Jews returning from prayers at the Cave of the Patriarchs were murdered and 20 wounded. In 2001, 10-month old Shalhevet Pass was intentionally shot in her stroller by a sniper lurking in the hills above the Old City. In 2003, a pregnant Israeli woman and her husband were killed when a suicide-bomber detonated next to them in the market on Shuhada Street.

Following the 1995 Oslo Agreement, Palestinian cities (such as Ramallah, Nablus and Jericho) were placed under the exclusive jurisdiction of the Palestinian Authority; large red signs warn Israelis that it is against the law for them to enter. This continues to the present day. No one calls this apartheid.

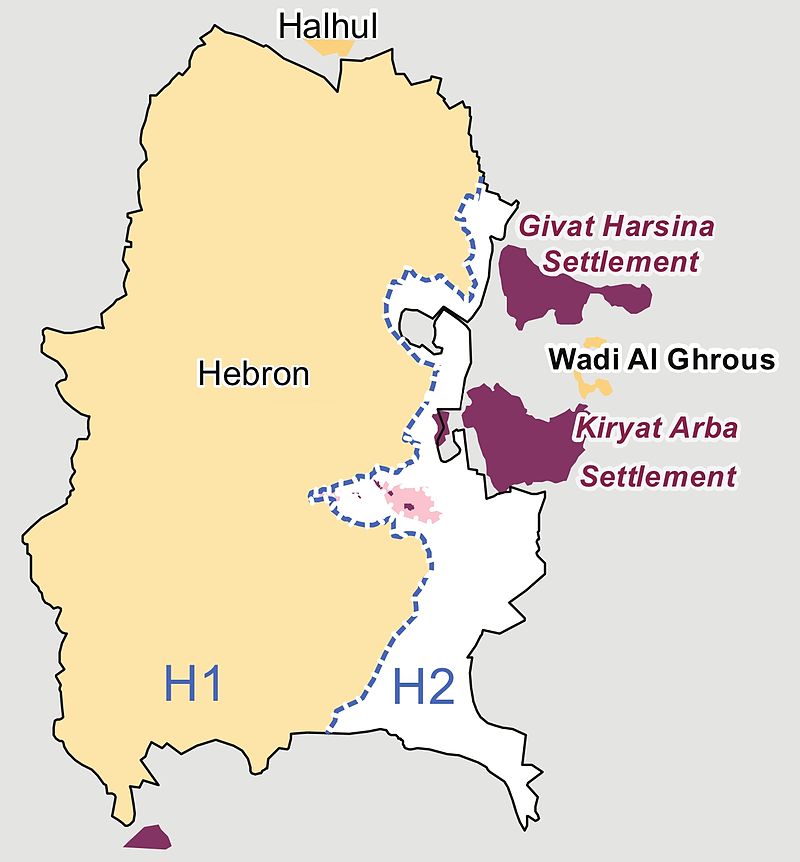

Because of the Jews’ historic ties to Hebron, that city was split into two sectors. Area H-1 is controlled by the P.A. and comprises more than 80 percent of the city. Approximately 170,000 Palestinians live in H1 and Jews (not just Israelis, but Jews from any country) are forbidden to enter (I know because on my recent tour of the area our group was asked whether there were any Jews before we were allowed to enter H1). Area H-2, comprising the remaining 20 percent of Hebron, is home to 30,000 Palestinians and approximately 500 Israelis who live under Israeli civil and security control.

The Cave of the Patriarchs, sacred to Christians and Muslims as well as to Jews, lies in Israeli-controlled H2, but is open to all.

Shuhada Street (“Martyr’s Street” in Arabic), in the old city of Hebron, is under Israeli control. The street used to be the central wholesale market of the Hebron region. Because of security threats to the Jewish families who live nearby, Palestinians who are not residents of H-2 are not allowed on Shuhada Street. The 30,000 Palestinians who are residents of H-2 are permitted to visit Shuhada Street. Most of the Arab shops on the street have closed and it is often referred to critically as a ghost town.

Shuhada Street has become central to the Palestinian narrative that Israel’s occupation of the West Bank constitutes an apartheid regime, according to Mustafa Barghouti, the Secretary General of the Palestinian National Initiative. There are hand-made signs on the street designating it as “Apartheid Street.”

There are annual “Open Shuhada Street” demonstrations held around the world. Many visitors to Hebron, including celebrity tourists, are brought to Shuhada Street to experience Israel’s alleged “apartheid” first-hand. The reactions to such visits are dramatic.

Pulitzer prize-winning American Jewish author Michael Chabon on a tour of Shuhada Street called it “the most grievous injustice I have ever seen in my life.” Chabon’s wife, Ayelet Waldman, also an author, was “shocked” to discover that “there were streets in Hebron that Palestinians were not allowed to tread,” adding that “when you’re not allowed to walk here because of your religion, that speaks to me of the Holocaust.”

Hollywood actor Richard Gere, after being escorted along Shuhada Street, likened the situation in Hebron to segregation in the Jim Crow-era American South. Also speaking of Shuhada Street, the head of progressive advocacy group J Street Jeremy Ben Ami said: “It is impossible to be a Jew and not feel shame at the way Palestinians are treated in the center of Hebron.”

These tours leave the impression that this five-block section of Hebron was shut down for racist reasons. They fail to fully explain the almost century-long history of violence by Arabs against Jews in Hebron that resulted in the closure of Shuhada Street.

Even more significant is that these tours fail to even mention (much less visit) the new Arab commercial district just a few blocks away in the much larger Palestinian-controlled H-1 section of the city. There, on Ein Sarah Street, is the thriving business area of Hebron, surrounded by almost 200,000 Palestinians (and no Jews, who are forbidden to enter H-1).

If any of those shocked by the “apartheid” of Shuhada Street were to visit this area they would see a flourishing commercial district complete with an ultra-modern indoor nine-story mall. There are Kentucky Fried Chicken and Domino’s Pizza franchises and all the accoutrements of a modern, sophisticated commercial area. They would see the real Palestinian Hebron, which is bustling with life: cars, bikes, food carts, families with small children, shop owners, people everywhere, going about their daily business.

One can Google Shuhada Street and find hundreds of articles condemning Israeli’s shuttering of the street and comparing it to apartheid (see, for example, here & here). However, there is little, if any, mention of the fact that the old Shuhada Street has been replaced by a thriving new commercial district.

One must search far and wide to discover that “Shuhada Street […] is not the main thoroughfare of Hebron as claimed. It is a comparatively small road in the Old City. Hebron is a large, thriving city, with massive factories, businesses and shopping malls. Hebron is the most prosperous city and main center of economy for the P.A., with more than 40 percent of the P.A. economy produced there. There are 17,000 factories and workshops in all areas of production. There are four hospitals, three universities and an indoor 4,000-seat basketball stadium.”

This is the Hebron very few visitors are allowed to see. This is the invisible counterpoint to the apartheid myth of Shuhada Street.

Many visitors to Hebron take a “dual narrative” tour of the city, where one spends half the day with an Israeli guide and half the day with a Palestinian guide. They truly believe that they are getting an accurate portrait of the city in this manner. However, none of the many descriptions of such tours found on the Internet (see here & here) even mention the new, prosperous commercial area of Hebron that is under Palestinian control and where Jews are forbidden to enter.

On my recent trip to Israel, I took one of these tours expecting to see both sides, including the new commercial district which offsets the tale of Shuhada Street. I repeatedly asked both guides when we were going to visit the new shopping center on Ein Sarah Street. The Israeli guide told me that Mohammed, the Palestinian guide, would take us there. Mohammed first denied that such a place existed, then mocked its significance and finally said there wouldn’t be time to go there. The other members of my tour had no idea why I wanted to go there. Mohammed did not explain.

My fellow travelers were left with the impression that the closed Shuhada Street represents the dead heart of Hebron’s market scene. And then they mistakenly conclude that Israel shuttered the street for racial reasons and accept the myth of Shuhada Street as representative of Israeli apartheid. No one left the wiser that apartheid in Hebron is a one-way street and that it runs against the Jews, not the Palestinians.

The real shame of Shuhada Street is not that a small number of Palestinians are prevented from going there, but that the Israeli army is needed to prevent the 85 Jewish families who live nearby from being massacred. The real problem in Hebron from a Palestinian point of view is that it is the only city under Palestinian control that allows even a small number of Jews to reside there.

The real apartheid in the West Bank lies not with the Israelis, but with the Palestinian leadership, who insist that any independent Palestinian state be judenrein (Jew-free) (as are most of the Palestinian cities in the West Bank), in sharp contrast to Israel proper where two million Arabs reside as full citizens and constitute 20 percent of the entire population.

The myth of Shuhada Street is a metaphor for the larger Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Like the rest of the Palestinian narrative, the myth of an apartheid Shuhada Street is grounded in misrepresentations, omissions and facts taken out of context. It lies at the heart of the Palestinian propaganda machine. It must be exposed and hopefully this piece can begin an honest dialogue to do so.

Steve Frank is an attorney, retired after a 30-year career as an appellate lawyer with the U.S. Department of Justice in Washington, D.C. His writings on Israel, the law and architecture have appeared in publications including “The Washington Post,” “The Chicago Tribune,” “The Jerusalem Post,” “The Times of Israel” and “Moment” magazine.