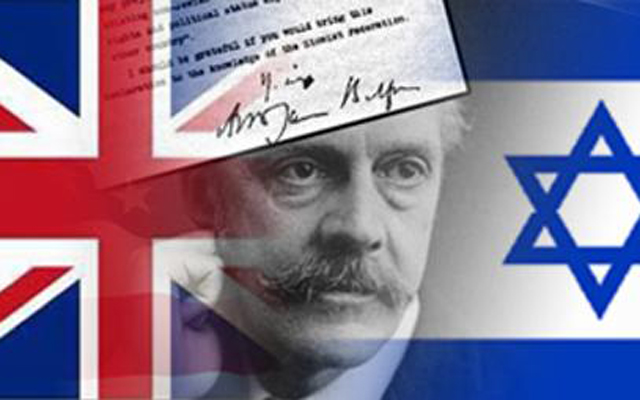

On November 2, we celebrated the 100th anniversary of the Balfour Declaration. Sent by British Foreign Secretary Lord Arthur James Balfour in a letter to Lord Rothschild, a leader of the British Jewish community, it read:

“His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”

The Importance of the Balfour Declaration for the Jewish People

For the Jews, this meant the British were supporting their dream of reestablishing a Jewish homeland in the land of Israel. At the San Remo Conference in San Remo, Italy, in April 1920, the Supreme Council of the Principal Allied Powers delineated the exact boundaries of the countries they had conquered at the end of World War I, and resolved that the Balfour Declaration would be incorporated in The Treaty of Peace with Turkey.

When the League of Nations formally confirmed the Mandate for Palestine in July 24, 1922, this acknowledged a pre-existing historical right of the Jews to the Land of Israel that they had never relinquished, as former Israeli ambassador Dore Gold noted. The Jewish people had been sovereign in the land for a thousand years until many were driven into exile. When the Muslims invaded Palestine in 634, ending four centuries of conflict between Persia and Rome, Israeli diplomat Yaakov Herzog noted, they found direct descendants of Jews who had lived in the country since the time of Joshua bin Nun, the man who led the Israelites into the Land of Canaan. This means that for 2,000 years, Jews and Christians constituted the majority of the indigenous population of Palestine, while the Bedouins were the ruling class under the Damascene caliphate.

Arab Response to the Balfour Declaration

The Arabs viewed the Balfour Declaration as a betrayal. The Balfour Declaration did not mention the Arab rights or Arab right to the land, only that the “civil and religious” rights of the inhabitants of Palestine are to be protected.

Reverend James Parkes, a pioneer in the study of anti-Semitism and the history of the Jewish people, countered that the British “did not ‘give away what belonged to the Arab people’; for it had already refused to recognize… on historical grounds, that the Arab claim to be exclusive owners of the country was justified.”

Furthermore, the British were quite clear that Palestine was not a state, but rather the name of a geographical area, asserts Eli Hertz. When the First Congress of Muslim-Christian Associations met in Jerusalem in February 1919 to select Palestinian Arab representatives for the Paris Peace Conference, they adopted the following resolution: “We consider Palestine as part of Arab Syria, as it has never been separated from it at any time. We are connected with it by national, religious, linguistic, natural, economic and geographical bonds.” There is no mention of the national rights of the Arab people.

Hertz adds that prior to Jews referring to themselves as Israelis in 1948, the term Palestine applied almost entirely to institutions established by Jews: The Jerusalem Post, founded in 1932, was called The Palestine Post; Bank Leumi L’Israel, incorporated in 1902, was called the Anglo Palestine Company until 1948; Israel Electric Corporation, founded in 1923, was initially called The Palestine Electric Company; and the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, founded in 1936, was originally called the Palestine Symphony Orchestra.

Zuhair Mushin, the head of the PLO military operations department, described how the Arabs adopted the ruse of a Palestinian people to destroy the Jewish state: “There are no differences between Jordanians, Palestinians, Syrians and Lebanese. Only for political reasons do we carefully underline our Palestinian identity. For it is of national interest for the Arabs to encourage the existence of the Palestinians against Zionism. Yes, the existence of a separate Palestinian identity is there only for tactical reasons. The establishment of a Palestinian state is a new expedient to continue the fight against Zionism and for Arab unity.”

Yet, the Arabs argued that the British promised Palestine to them, as a result of the correspondence between Sir Arthur Henry McMahon, the British High Commissioner in Egypt, and Husain Ibn Ali, the Sharif of Mecca, beginning in 1915. In return for leading a revolt against the Turks, the Sharif would receive significant areas of the disintegrating Ottoman Empire.

A ‘Twice Promised Land’?

Asked whether Palestine was part of this agreement and thus a “twice promised” land, historian Efraim Karsh emphatically said no. “In his correspondence with Sharif Hussein of Mecca, which led to the Great Arab Revolt during World War I, Sir Henry McMahon…specifically excluded Palestine from the prospective Arab empire promised to Hussein. This was acknowledged by the Sharif in their exchanges and also by his son Faisal, the future founding monarch of Iraq, shortly after the war.”

Karsh added, this has not precluded “successive generations of pan-Arabists and their Western champions from charging Britain with a shameless betrayal of its wartime pledge.”

The Arab Revolt?

With regard to the Arab Revolt, Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen, the chief British political officer for Palestine, remarked that the “Arabs of Palestine, far from contributing anything toward the ultimate victory [during WWI], actively opposed us and deserve no better treatment than others…”

Philip Graves, The London Times Middle East correspondent who served in the British Army from 1915-1919, declared, “Most annoying to anyone who has served with the British forces or the Sherifian Arab forces in the Palestine campaign…are the pretensions of the Arabs in Palestine to have rendered important services to the Allies…”

They “confined themselves to deserting in large numbers to the British, who fed and clothed and paid for the maintenance of many thousand such prisoners of war, few indeed of whom could be induced to obtain their liberty by serving in the Sherifian Army.”

A final note: In April 1931, David Lloyd George, who had been Prime Minister of England when the Imperial Cabinet formulated the idea of a national home, explained the justification for the Balfour Declaration: “The Jews surely have a special claim on Canaan. They are the only people who have made a success of it during the past 3,000 years. They are the only people who have made its name immortal, and as a race, they have no other home. This was their first; this has been their only home…. Since their long exile… this is the time and opportunity for enabling them once more to recreate their lives as a separate people in their old home and to make their contribution to humanity as a separate people, having a habitation in the land which inspired their forefathers.”

By Alex Grobman, PhD

Alex Grobman, a Hebrew University-trained historian, has written extensively in books and articles on the Palestinian Arab conflict. He is a member of the Council of Scholars for Scholars for Peace in the Middle East (SPME), and a member of the Advisory Board of The Endowment for Middle East Truth (EMET). He has trained students how to respond to Arab propaganda on American campuses. One student, who worked with him for three years, became president of Harvard Students for Israel.