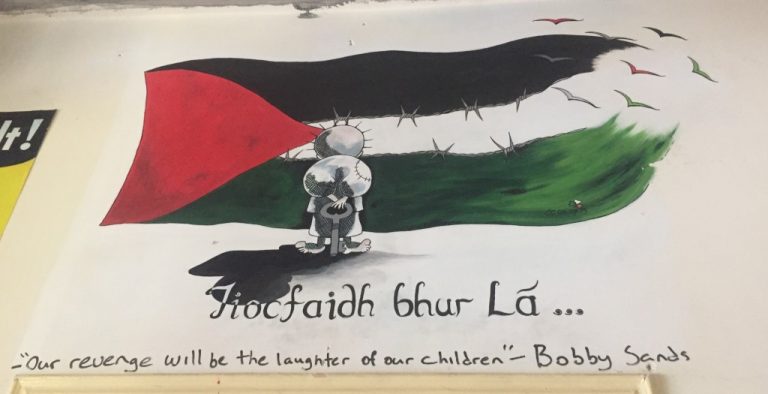

Our revenge will be the laughter of our children”; painted on a wall inside of the “Hostel in Ramallah.” (Lilia Gaufberg)

This past July, at the peak of another sweltering Israeli summer, I hopped onto bus 218 from Jerusalem to Ramallah, the primary Palestinian-Arab city in area A of Judea and Samaria, more commonly known as the West Bank. 45 minutes and one security checkpoint later, the rolling hills of Jerusalem, dotted with the blue and white of the Israeli flag, blended into bustling landscapes sprinkled with red, black, and green.

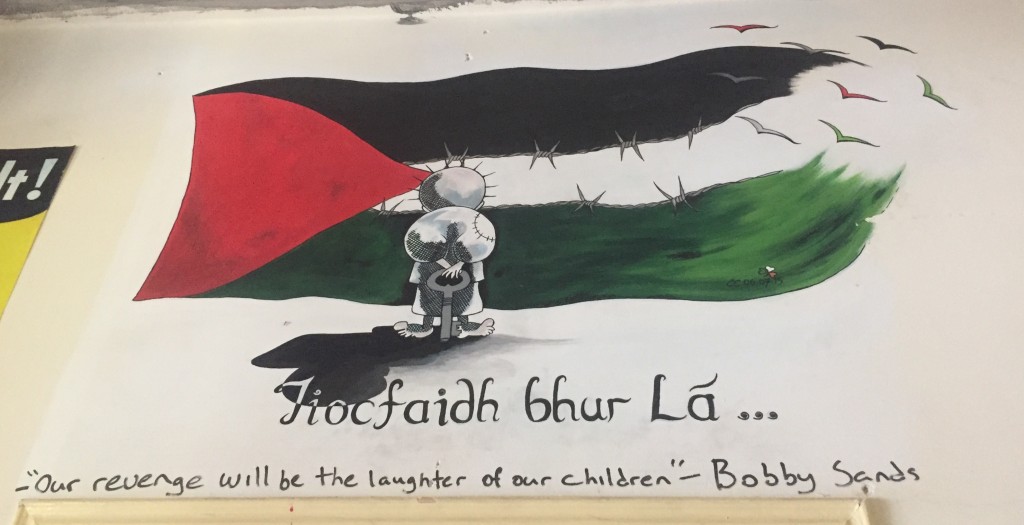

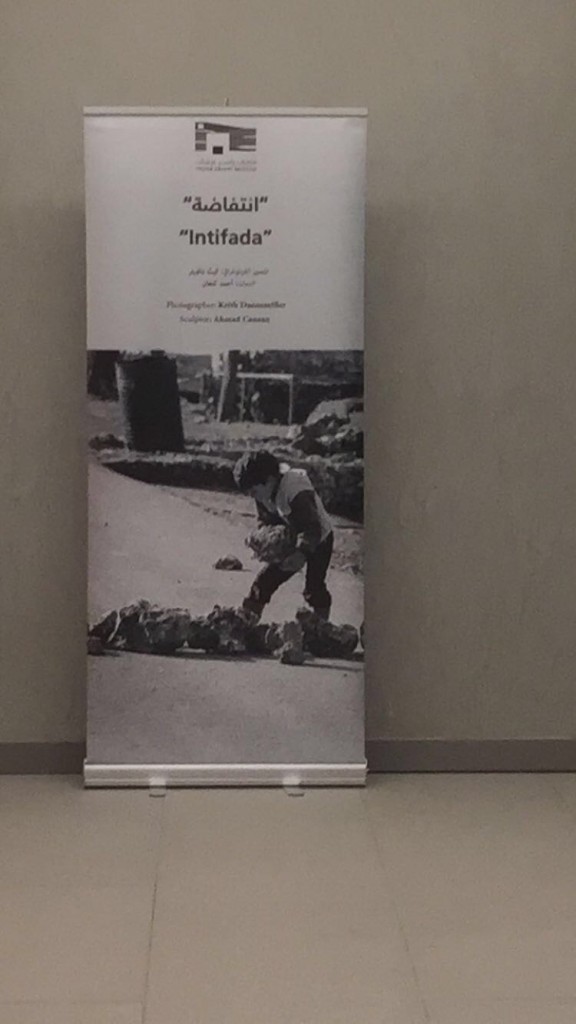

Ramallah is a city like any other: alive with sounds and smells, ripe with an energy unique to largely populated areas. In Ramallah, I saw gorgeous apartment buildings, schools, and towering mosques contrasted with littered streets. In Ramallah, I witnessed girls in tank tops and shorts drinking iced coffees in front of mosques during the call to prayer. In this landscape of life, one overwhelming element felt out of place: in Ramallah, everywhere you turn, a vehement hatred of Israel and a denial of Jewish history in the land of Israel pulses throughout the city, an overwhelming undercurrent of identity oppression. In Ramallah, streets and squares are named after internationally recognized terrorists. In Ramallah, the main museum in the center of the city, entitled “Yasser Arafat Museum”, complete with marble floors, decorated guards, and an extravagant wading pool, contains exhibits which praise the “intifadas”, the terror wars, inflicted upon Jews and largely orchestrated by Palestinian leaders themselves.

An upcoming exhibit at the Yasser Arafat Museum entitled “Intifada.” (Lilia Gaufberg)

(Lilia Gaufberg)

Ramallah is a city of contrast: people on the streets are warm and welcoming, but the city speaks of a consensus towards the complete destruction of Israel and, ultimately, the Jewish people. In Ramallah, mothers and their children walk down streets with images of murderers pasted on the walls of shops and cafes. In Ramallah, the advocating of violence strategically masked under the noble guises of “revenge” and “resistance” is rampant. I wanted to see the other side, so to speak. I went into my experience in Ramallah with an open mind and heart, with the aim to truly understand the perceptions and grievances of the people living there. What I saw was this: a vibrant city, one like any other, with misplaced, unjustified hatred lining its foundations.

Images of terrorists posted around the streets of Ramallah. (Lilia Gaufberg)

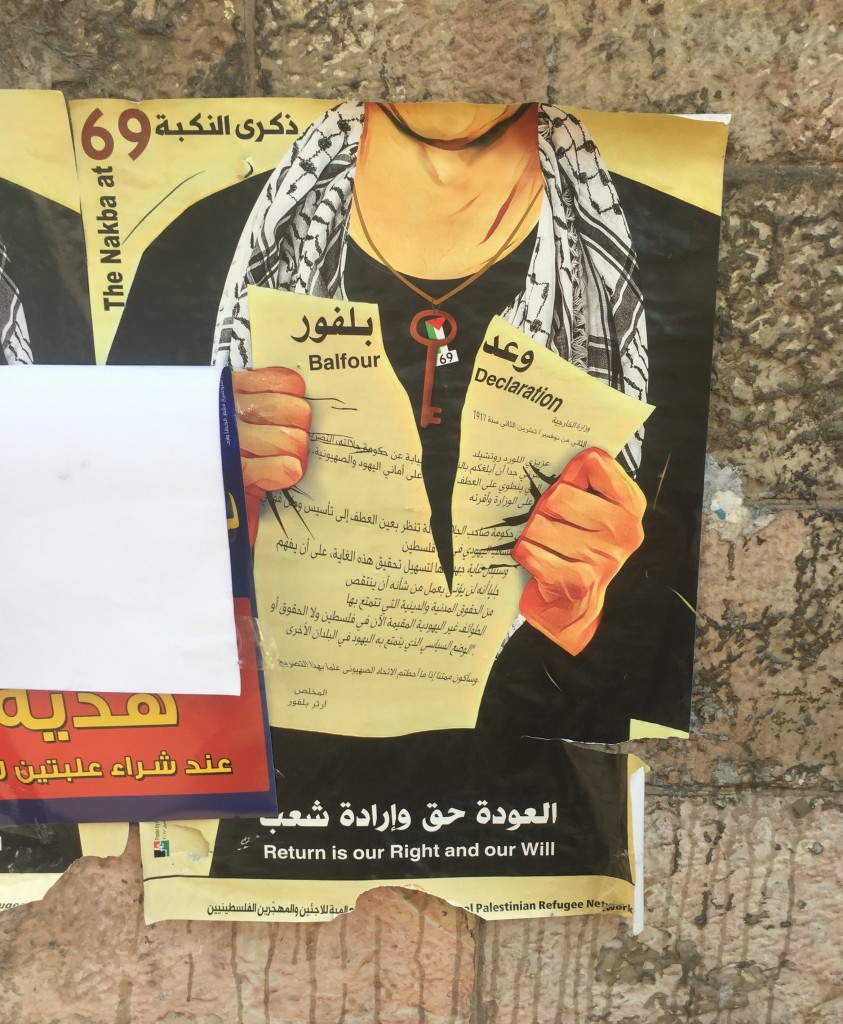

An image of a person in a Palestinian keffiyeh, a symbol of Palestinian militancy and terror, ripping up the Balfour Declaration. Posted along the streets of Ramallah. (Lilia Gaufberg)

The most powerful propaganda is the kind that is subtle; it blends in seamlessly with everyday surroundings, a constant, steady backdrop in the hustle of everyday life. It clings to the air like a layer of impenetrable, inconspicuous fog. Those who are influenced most by propaganda are not at all cognizant of its brainwashing effects. A hatred of Israel and a narrative of injustice towards the “Palestinian people” is woven into the societal fabric of cities like Ramallah, an integral part of the city’s character. Ramallah is the current capital of the Palestinian Authority, and, in the typical “two-state solution” paradigm, Ramallah would be the most important city in the Palestinian state. Seeing Ramallah with my own two eyes confirmed my deep skepticism over the idea of two states in the land of Israel: that a Palestinian state with the current mode d’operant, the current mindset, of Ramallah, in which the most elaborate building in the city is one which commemorates a killer, in which a detestation of the Jewish state is spread over the city like a plague, would be nothing less than a kleptocratic society based on hatred and a narrative of victimhood. This reality would mean a dismal future for Palestinian-Arabs.

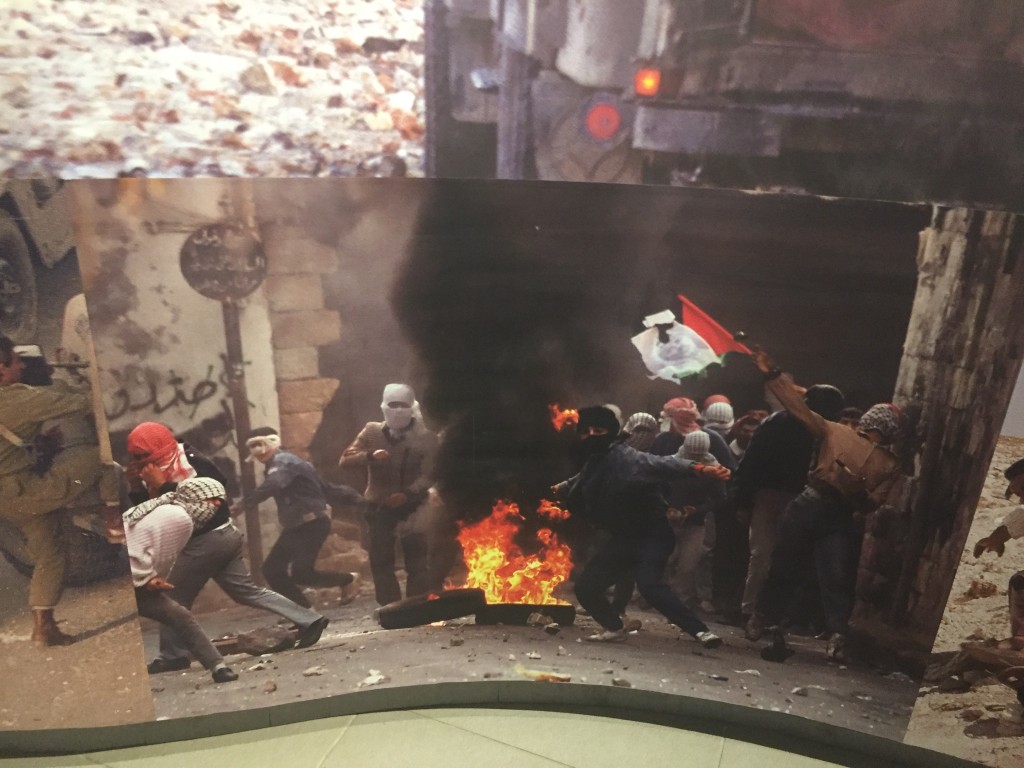

An image of Palestinian-Arabs in keffiyehs throwing Molotov cocktails. Yasser Arafat Museum. (Lilia Gaufberg)

For those who, like myself, aim to advocate for justice and for the realization of peace for all people, a Palestinian state with Ramallah as its capital, and therefore, a state built on violence, vehement hatred, and the longing for the destruction of an entire nation, would be the antithesis to these liberal ideals.

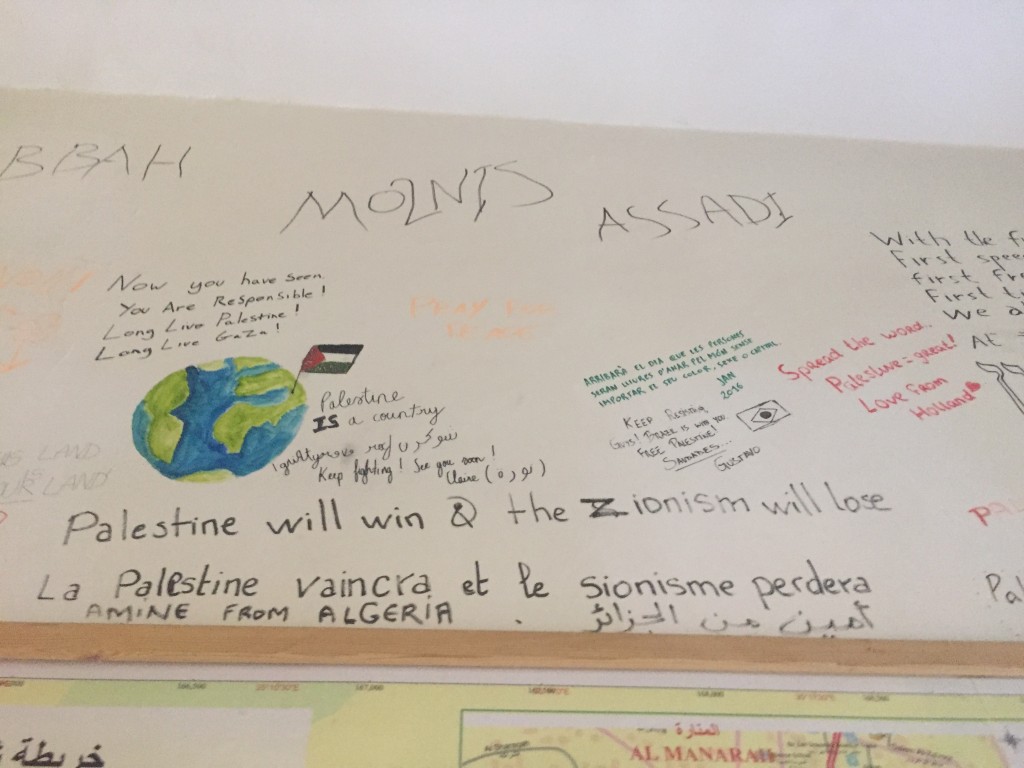

“Palestine will win and the Zionism will lose”; written on a wall inside of the “Hostel in Ramallah.” (Lilia Gaufberg)

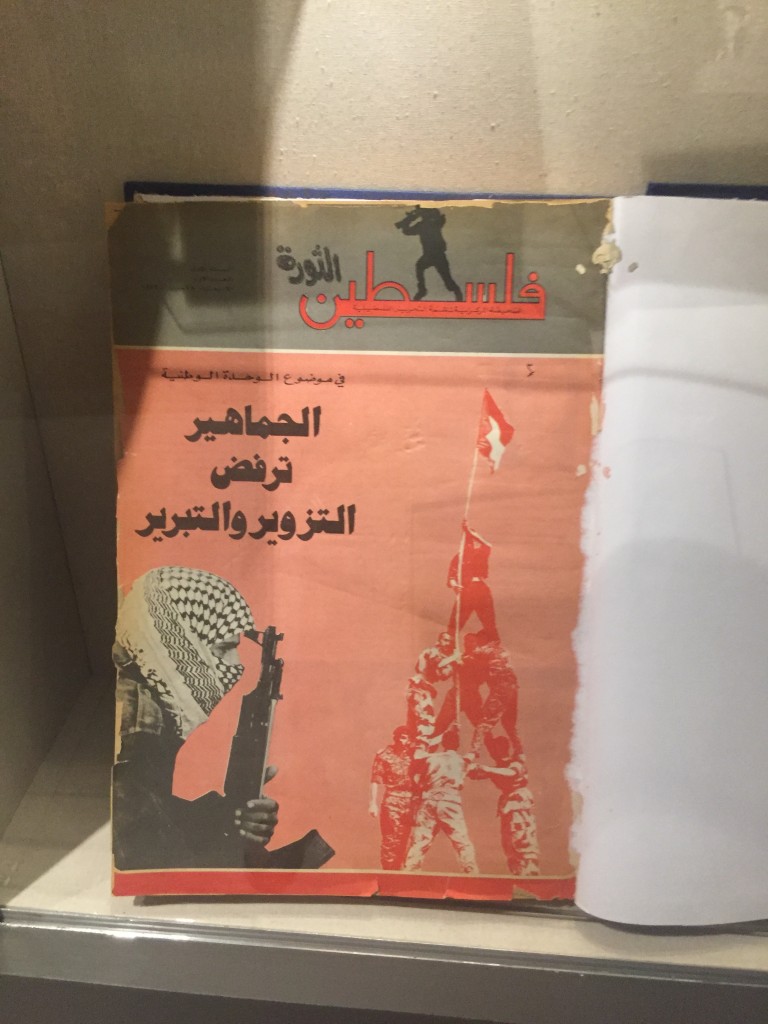

A man in a Palestinian keffiyeh, a garment used to symbolize militant “resistance”, holding a gun. Yasser Arafat Museum. (Lilia Gaufberg)

Graffiti of a man carrying a keffiyeh-patterned Israel on his back. Ramallah. (Lilia Gaufberg)