Daniel Greenfield, a Shillman Journalism Fellow at the Freedom Center, is an investigative journalist and writer focusing on the radical Left and Islamic terrorism.

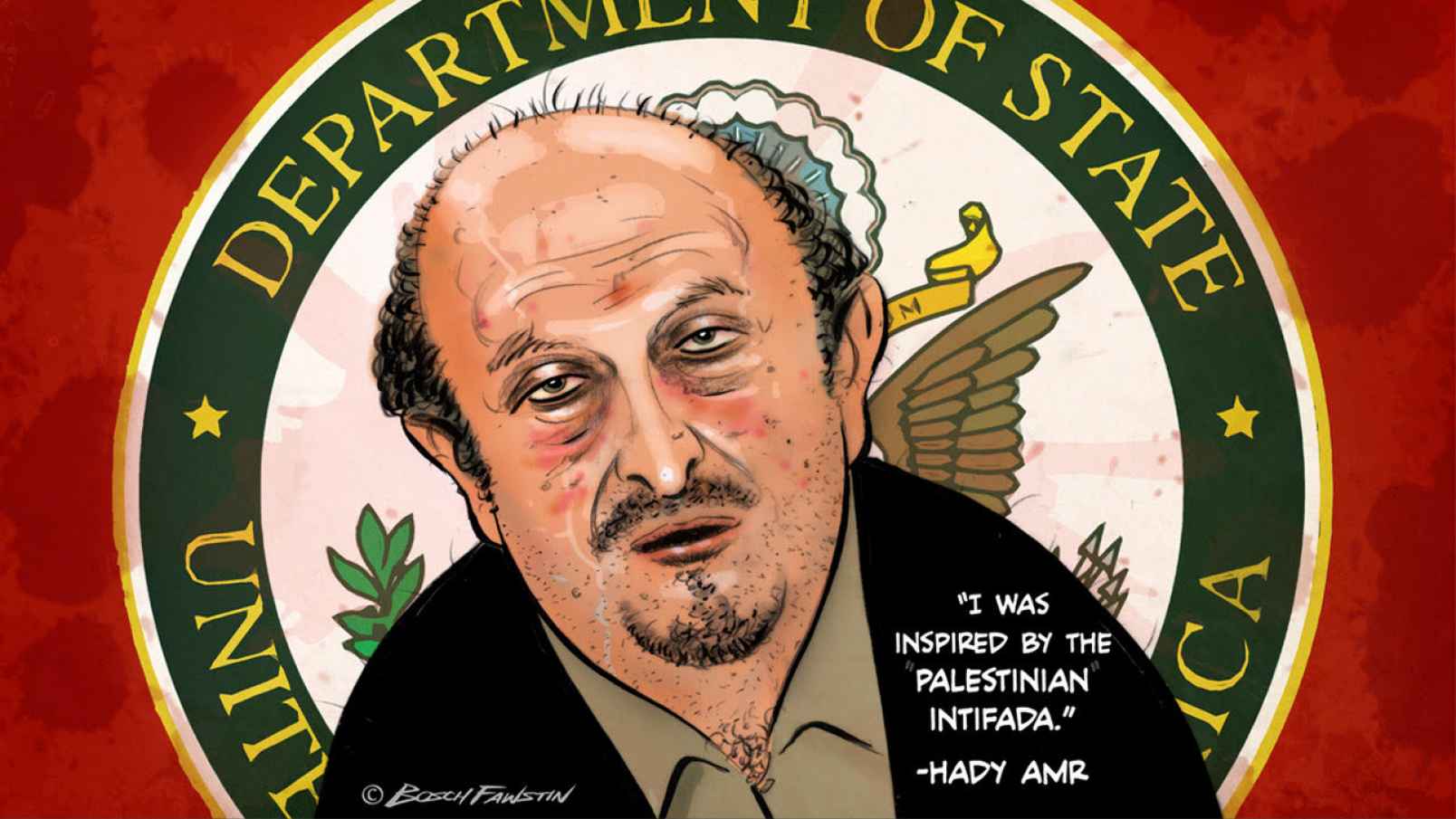

“I was inspired by the Palestinian intifada,” Hady Amr wrote a year after September 11, discussing his work as the national coordinator of the anti-Israel Middle East Justice Network.

Biden has now chosen Amr as a Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Israel-Palestine.

“I have news for every Israeli,” Amr ranted in one column written after Sheikh Salah Shahada, the head of Hamas’ Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades, was taken out by an Israeli air strike.

Amr warned that Arabs “now have televisions, and they will never, never forget what the Israeli people, the Israeli military and Israeli democracy have done to Palestinian children. And there will be thousands who will seek to avenge these brutal murders of innocents.”

He also threatened Americans that “we too shouldn’t be shocked when our military assistance to Israel and our security council vetoes that keep on protecting Israel come back to haunt us”

The future State Department official was making these threats less than a year after 9/11.

Hady Amr had accused Israel of “ethnic cleansing” and coordinated an organization that had accused Israel of “apartheid” making his appointment, like that of Maher Bitar, an anti-Israel activist appointed as the Senior Director for Intelligence on the NSC, a statement about the Biden administration’s hostile relationship to the Jewish State.

Amr’s job offer from Biden isn’t surprising. The Beirut-born Amr who grew up in Saudi Arabia had dived into politics as the director of ethnic outreach for Al Gore’s failed presidential campaign. And the Biden campaign listed Amr as one of its bundlers who fueled it with cash.

Biden’s move puts Amr, who had repeatedly advocated for a deal with Hamas, and worked closely with a terror state that serves as a major backer of Hamas, in a key policy position.

But Amr isn’t just another foreign policy expert with a history of hostility to Israel.

“What’s exciting about this project is that it’s a joint project of Brookings and the Qatari Government,” Hady Amr had gushed about his old role as the director of the Brookings Doha Center, whose aim he said was to “inform the American public and American policy makers”.

In, “Foreign Powers Buy Influence at Think Tanks”, the New York Times had reported that Qatar, an ally of Iran and the Muslim Brotherhood, was the single biggest foreign donor to the Brookings Institute.

“There was a no-go zone when it came to criticizing the Qatari government,” a visiting fellow at the Brookings Doha Center in Qatar in 2009 had told the Times.

Hady Amr had been the founding director of the Brookings Doha Center and had led it between 2006 and 2010. A Times report noted that the institution had forbade criticism of Qatar. Lawyers interviewed by the paper suggested that some of Brookings’ work with foreign governments merited “registration as foreign agents”. Brookings has not only not done so, its key personnel, like Amr, have gone on to work in important positions for the United States government.

Amr moved back and forth between Brookings and the United States Government, working for Brookings Doha and then the State Department, and returning to Brookings under the Trump Administration, before coming back to the State Department under Biden.

Qatar not only provided $14.8 million in funding for the Brookings Doha Center, but its advisory board was co-chaired by Qatar’s foreign prime minister and a member of its royal dynasty while its director had formerly worked for the second of the Qatari Emir’s three wives (and the only wife who also wasn’t a cousin) making it obvious that the organization was under Qatari control.

“The center will assume its role in reflecting the bright image of Qatar,” the Qatari Foreign Ministry had boasted.

Qatar is a major state sponsor of the Islamic terrorist group Hamas. It has been accused by US government officials of being utilized by Al Qaeda and the Taliban for fundraising purposes. Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the mastermind of September 11, operated out of Qatar. He fled after being warned by a member of the Qatari royal family that the Americans were on to him.

“The Qataris had a history of terrorist sympathies,” the NSC’s former chief counter-terrorism adviser wrote. “It has been true that Qatar has served as a sanctuary for leaders of groups that the U.S. or other countries deem to be terrorist organizations.”

Hady Amr’s backing for Islamists mirrored the support for Islamists by the Qatari regime.

At Brookings Doha, Amr had urged that the “Muslim brotherhood organizations across the Muslim World should be engaged”. Then he wondered, “in Lebanese and Palestinian society, the faith-based organizations are seen as the least corrupt… Hamas and Hezbollah are often cited by their populations as being non-corrupt. This needs more analysis. Is this the case?”

Over the past few years, Amr has repeatedly urged negotiations with Hamas. When the Trump administration unveiled its proposed peace deal, Amr co-wrote an article declaring that it should be scrapped in favor of focusing on a deal with Hamas. The article provides some insight into the policies that Amr may advance as a Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Israel-Palestine.

“By laying out the terms of a three-way Hamas-Israel-PA/PLO deal now, and building an international consensus around it, the United States could create a pathway toward resolution,” the article had argued. That would potentially not only restart Obama’s attempt to impose a plan on Israel, but would do so not only on behalf of the PLO, but also on behalf of Hamas.

The troubling connections between Qatar, an Islamic terrorist state that is allied with Iran, is a major sponsor of the Muslim Brotherhood and its terrorist arm, Hamas, and the influential Brookings Institute think-tank makes Amr’s appointment all the more problematic.

“Our business is to influence policy,” Martin Indyk admitted. “To be policy-relevant, we need to engage policy makers.”

Indyk, a key anti-Israel figure in the Democrat foreign policy establishment, who had worked for Clinton and Obama, had partnered with the Qatari government to set up Brookings in Doha.

Amr’s career was fueled by his work with Indyk and after Brookings, he went to work for the State Department and eventually became the Deputy to the Special Envoy for Israeli-Palestinian Negotiations for Economics and Gaza under Obama. Now, after acting as a big money bundler for Biden, the anti-Israel figure has been rewarded with a major foreign policy role.

Hady Amr is not the only Brookings Doha alumnus to end up in a top policy position. Amr’s appointment may be an opportunity to scrutinize whether employees of an organization that effectively functioned as an arm of a foreign government should be allowed to hold such roles.

Through Al Jazeera and organizations like Brookings Doha, Qatar has worked to support and normalize Islamist groups like the Muslim Brotherhood. Brookings Doha’s leadership made no secret of the fact that its goal was to influence policymakers. But, even more troublingly, the veterans of Brookings Doha, like Amr, are becoming policymakers in their own right.

Should foreign governments like Qatar be able to exercise such an influence over America?