(This piece was first published by IMPACT-SE: https://www.impact-se.org/a-middle-east-scholars-evaluation-of-the-george-eckert-institute-report-on-palestinian-textbooks/)

The Georg Eckert Institute for International Textbook Research has recently completed a research of 174 textbooks and 16 teachers’ guides for grades 1-12 published by the Palestinian Authority (PA) in the years 2017-2020, plus additional 7 textbooks published by the PA and modified by the Israeli authorities for use in East Jerusalem schools. The research was initiated by the European Parliament upon requests by some members thereof who had expressed concern about anti-Semitic and anti-peace contents found in the books by previous researchers, chiefly the teams of the Institute for Monitoring Peace And Cultural Tolerance in School Education (IMPACT-SE, formerly the Center for Monitoring the Impact of Peace – CMIP) and the author of this paper, throughout their consecutive studies of these books conducted during the years 2000-2020. The European Union financially supports both the PA and the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for the Palestine refugees (UNRWA) that uses these books as well, and it was necessary to ascertain the existence of such contents in the books prior to taking further decisions.

Having studied the attitude to the “other” and to peace in various Middle Eastern curricula, including the Palestinian one, since 2000, I was curious to look into the Georg Eckert Institute’s report (to be referred to henceforth as “the report”). The following is my initial impressions of its findings.

Some of the report’s findings appearing in both its General Conclusion and Executive Summary are similar to those found in previous studies, and I quote:

- “One textbook provides a learning context that displays anti-Semitic motives and links characteristics and actions attributed to Jews at the dawn of Islam to the current Israeli-Palestinian conflict” (Executive Summary, p. 4).

- “The textbooks affirm the importance of human rights in general and in several places explicitly highlight a universal notion of these rights… This universal notion is, however, not carried through to a discussion of the rights of Israelis” (Executive Summary, p. 3).

- “In numerous instances the textbooks call for tolerance, mercy, forgiveness and justice and encourage students to help others, fight corruption and respect human values. They do not apply these notions to Israel and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict” (General Conclusion, p. 170).

- “…when the topics of… coexistence and tolerance are raised, no link is established to the current conflict” (General Conclusion, p.170).

- “The cartographic representation of All-Palestine, as a political entity, a geographical region or an imagined homeland, generally do not include the State of Israel or cities founded by Jewish immigrants” (Executive Summary, p. 4).

- “The term ‘Israel’ occurs relatively seldom, while the term ‘(Zionist) occupation’ dominates in the books” (Executive Summary, p. 4).

- “The recognition of Israel’s right to live in peace and security documented in the letter by Yasser Arafat to Yitzhak Rabin stands in contrast to the questioning of the legitimacy of the State of Israel expressed in other passages and textbooks” (Executive Summary, p. 4).

- “Textbooks for Arabic language contain emotionally laden depictions of Israeli violence that tend to dehumanise the Israeli adversary, occasionally accusing the latter of malice and deceitful behaviour… Violence perpetrated by Palestinians, including violence against civilians, is presented as a legitimate means of resistance…” (Executive Summary, p. 4).

Nevertheless, the bottom line of the report is: “the textbooks adhere to UNESCO standards” (Executive Summary, p. 3). That leaves the reader a bit perplexed: do anti-Semitism, de-legitimization of both the existence of the State of Israel and the presence of Jews in the country (symbolized by the absence of their cities from the maps), non-application of human rights to their case, non-application of the principles of co-existence and tolerance to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the approval of violence against Israeli civilians – all conform to UNESCO standards?

Let us, first, look at these standards. The report cites (on p. 23) several principles taken from a UNESCO document published in 2014 (UNESCO Education Sector: Textbooks and Learning Resources: Guidelines for Developers and Users). They include: realistic, balanced and respectful representation of different groups, providing examples of diverse groups living together harmoniously, focusing on cultural, social and religious values that support peaceful coexistence, commitment to human rights, a comparative approach to the teaching of religions and the promotion of attitudes and skills for conflict prevention and peace building.

The report also relies on a “broad academic consensus” which regards textbook items as (1) fostering tolerance if they acknowledge human rights, promote tolerance and respect and portray relevant others positively, (2) promoting violence if they explicitly call for violent actions or consider them legitimate in the framework of the conflict, and (3) potentially igniting hatred if they deny any specific group its human rights or depict it in terms that denote inferiority, competition, aggression, non-reference to the individual ‘other’, dehumanization, deception and negation of the other group’s existence – on maps, in history, etc. (pp. 24-25).

These are good criteria to start with and the relevant source material available for the report was ample, although not complete (over 50 textbooks and teachers’ guides were not included).

The division of the report into chapters seems questionable. Chapter 3 deals specifically with the conflict (pp. 67-123 in the report). By contrast, Chapter 2, titled “Global Citizenship Education”, is wholly dedicated to internal Palestinian affairs unrelated to the conflict, such as political participation, environmental issues, diversity and intercultural understanding, human rights education and civic education in general (pp. 33-66). None of these issues includes references to Jews or Israelis, except for the presentation of Israel as a serial violator of Palestinians’ human rights (pp. 57-64) and as an environmental detriment. One may wonder what was the purpose of the inclusion of such a long chapter in the report other than showing the PA textbooks as meeting UNESCO standards in the field of civic and human rights education, even though they fall short of applying these standards to Israel and the Jews.

Chapter 4, titled “Real-Life Connections in Textbooks (RLC)” (pp. 124-136) has raised my impression that it was set aside specifically to legitimize the PA tendency to instill various aspects of the conflict in textbooks of purely scientific and economic school subjects, such as mathematics, sciences, technology, scientific education, management and economy, etc., as part of what might be seen as hate indoctrination. The chapter provides examples of mathematics, science and language assignments and exercises “amplifying the negative characterization of the opponent in the conflict… and, therefore, do not contribute to reducing feelings of hatred towards the other”. Yet, the authors of the report find an excuse for this hatred indoctrination because “the inclusion of RLC in textbooks corresponds with a UNESCO recommendation” (p. 136).

The report also includes two shorter chapters: the first one (pp. 137-154) reviews the changes introduced into some of the textbooks published in 2020. These specific books became available to the authors of the report who were quick to notice the improvements therein and add them to their analysis.

The second short chapter (pp. 155-169) reviews the amendments introduced by the Israeli authorities to the PA textbooks for use in East Jerusalem schools. It is interesting to note in this case that the authors of the report tend to endorse a negative attitude to these amendments – “the Israeli authorities’ interference in the content of textbooks is the employment of ‘a policy of power…'” (p. 169), but one should also bear in mind that these amendments present Israel side by side with Palestine (as seen on pp. 165 and 166 of the report, for example), unlike the original PA textbooks that ignore Israel’s very existence. Another amendment replaces a scene of violent conflict between Palestinians and Israelis with another one of cooperation (pp. 168-169), which, in my opinion, better suits UNESCO’s educational principles. Besides, the inserted scene is an RLC item as much as the replaced one.

Chapter 3, titled “Conflict in Textbooks”, contains several parts dealing with the use of the terms Israel, Zionists and Jews, the concepts of Jihad and Martyrs (Shuhada’), maps and the narrative of the “Right of Return”, as well as the portrayal of Jews in religious contexts, of Israeli and Palestinian violence within the conflict and of the peace process.

In all these fields the authors of the report seemingly try to downplay, or to explain away, textbooks items that hardly fit in with the afore-mentioned UNESCO standards and the “broad academic consensus” categories. Thus, alongside their admittance that the extensive use of the term “Zionist occupation” instead of Israel’s name “could be interpreted as questioning the legitimacy of the State of Israel, its political existence as an international legal entity thus being symbolically negated”, they also say that it “can be interpreted as referring to the effects of Israel’s occupation policy in the occupied territories” (p. 69), in an attempt to diminish the delegitimizing character of this usage.

Alongside the clear assertion that “none of the geographical maps of the region… depicts Israel as a state” and “this imagined territorial entity of Palestine negates the existence of the State of Israel”, it is also stated that this map of All-Palestine “has become an important unifying symbol of Palestinian national identity” (p. 75) and therefore, presumably, acceptable.

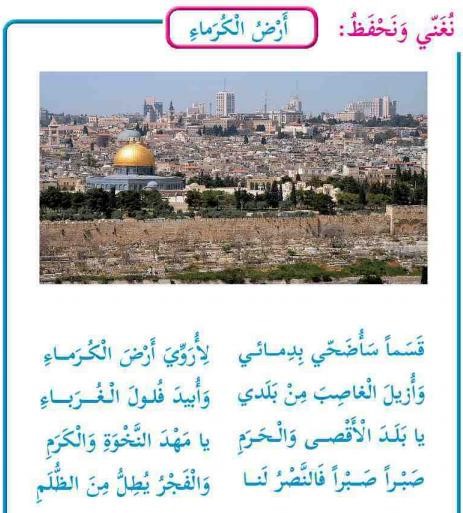

To the various maps given in this section (pp. 76-80), which mostly show Palestine in a non-political framework and, therefore, do not negate Israel specifically, other than omitting its name, I would add two more, which better make the point of Israel’s negation: Lesson 2, titled “Palestine is Arab and Muslim”, in the National and Social Upbringing textbooks for grade 4, part 1 (the latest example is from 2020, p. 8), presents a “Map of the Arab Homeland” in which the whole country is painted in one color and named “Palestine” under the Palestinian flag.

The other example has appeared in Science and Life textbooks for grade 3, part 1 (the latest being from 2020 on p. 65), as an item sold to tourists and clearly showing that there is no room for Israel in “FREE PALESTINE”:

Had the authors of the report used these maps and some similar other ones, side by side with the maps given in the report, they would have shed more light on the Palestinian delegitimization of the very existence of the State of Israel and, by extension, on the ultimate goal of the Palestinian struggle for liberation from Israeli occupation, namely, the “elimination” of the State of Israel and the “removal” of its “colonialist” Jewish citizens.

The authors of the report do not ignore the anti-Semitic nature of certain paragraphs describing the Jews of Arabia within their political rivalry with the Prophet of Islam (p. 89), but they tend to reduce the impact of this attitude on the general outlook to Jews today by mentioning a distinction made in a teacher’s guide between Judaism as a divine religion and Zionism as a colonial political movement (p. 70). But this very book presents an appreciation table where Judaism is as evil as Zionism, if not more so. The following chart, titled “Chart 2: Matrix of Accomplishment Levels” contains three subjects to be tested, with the available grades of “Good (3)”, “Satisfactory (2)” and “Unsatisfactory (1)”. The bottom line within the chart (marked in red) reads:

“[Test/Level of Accomplishment]: Clarification of the Zionist gangs’ goal of perpetrating massacres.

[Good (3)]: [The student] connected accurately the perpetration of the Zionist massacres to the Jewish religious thinking.”

[Satisfactory (2)]: [The student] connected correctly the thinking of the Zionist gangs to their perpetration of massacres.

Unsatisfactory (1): [The student] defined correctly the Zionist gangs’ goal of perpetrating massacres [but did not connect that to the Jewish or Zionist thinking!]”

(Teacher’s guide, Geography and Modern and Contemporary History of Palestine, Grade 10 (2018) p. 164)

What else should be said to convince the authors of the report that anti-Semitism is alive and kicking not only in historical contexts but also in the context of the conflict?

While dealing with Palestinian violence against Israelis, the authors of the report cannot and do not ignore its related aspect of terrorism (p. 110 and see their reference to the suicide bombings during the second Intifadhah on p. 107). But they try to counter-balance that by emphasizing the non-violent aspect of Palestinian struggle throughout this section, which is also indicated by the title they have chosen for it – “3.4.1. Violent and Peaceful Means of Palestinian Resistance” (p. 103).

Another way of playing down Palestinian violent approach towards Israelis is the treatment by the authors of the report of a gruesome literary expression describing the burning of Jewish settlers in a bus near Ramallah by Molotov cocktails as “barbecue party”. Instead of fully denouncing such an expression that is extremely inhuman, they distastefully define it as a “cynical statement” that cannot be interpreted as “a direct call for violence” (p. 112). Luckily for all, this particular expression was omitted from the 2020 edition of the book.

A special section in the report is dedicated to the coverage in the PA textbooks of Dalal al-Mughrabi, the woman who led the terrorist attack on an Israeli civilian bus on Israel’s Coastal Highway in 1978 in which over thirty Israelis, including women and children were murdered. The authors analyze that coverage and conclude that, like other cases worldwide, “violence against civilians equally occupies a historical space in the narrative of the Palestinian nation-building” (p. 117).

The final section in this chapter deals with the peace process which is covered in a few pages in a history textbook for grade 10 (p. 118). Also included there is Yasser Arafat’s letter to Yitzhak Rabin, prior to the signing of the Oslo Accords in 1993, in which he recognizes Israel’s right to live in peace and security and renounces terror. The authors of the report rightly determine that this is the only mentioning of the possibility of a peaceful resolution of the conflict in the entire body of textbooks studied (p. 120). In my opinion, they should have stressed the absence of peace and coexistence advocacy in the Palestinian curriculum in stronger terms.

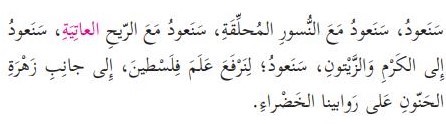

Mistranslation in the report has been found as well, grossly distorting the perception of future Palestine after its liberation, or, in other words: what should be done with the surviving Jews? A poem appearing in an Arabic language textbook for grade 3 answers this question as follows:

“I swear, I shall sacrifice my blood

in order to water the land of the noble ones

And to remove the usurper [Israel] from my country

and to exterminate [ubid] the foreigners’ defeated remnants [fulul]

O land of Al-Aqsa and the sanctuary

O cradle of dignity and nobleness

Patience, patience, for victory is ours

and dawn is peeping from the darkness”

(Our Beautiful Language, Grade 3, Part 2 (2019) p. 66. Emphasis added. This poem was replaced by a less violent one in the textbook edition of 2020, as accurately mentioned in the report – p. 139).

However, the translated part of this poem within the report omits the word “exterminate” ubid in Arabic – أبيد (line 2, section 2, first word). It says instead:

“…to kick out the violators and strangers from my country…” (p. 139).

An item in the PA curriculum carrying murderous connotations has thus been blurred. Such a case of mistranslation is problematic for an academic work, as it might insinuate a biased approach and an attempt to hide an uneasy evidence. Especially so, when this poem has become popular and is sung in class in many schools (example: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yan7tf3E6UU – this link was found usable on October 4, 2021 23:20 Israel time). No one can be sure that this habit has been stopped even though the poem itself has been removed from the curriculum.

Similar perceptions of future Palestine were also ignored, such as the one integrating the “right of return” into the violent struggle of liberation. The refugees, or their descendants, will not return to Israel to live in peace with their neighbors, as stated by the UN 194 Resolution of 1948. Rather, they will return to raise the Palestinian flag on the regions they will liberate:

“We shall return; we shall return with the soaring eagles; we shall return with the fiercely blowing wind; we shall return to the vineyard and the olive trees; we shall return in order to hoist the flag of Palestine next to the anemone flower on our green hills.”

(Arabic Language, Grade 5, Part 1 (2020) p. 84)

Finally, I have missed in the report two important elements:

- What should have been in the textbooks, as far as UNESCO principles are concerned, and is absent: Peace and co-existence advocacy, respectful representation of the adversary – including its history and religion (which was partially done in the PA textbooks prior to 2016 and then removed), application of human rights to its case.

- The general picture. It is expected from a report researching 190 textbooks and teachers’ guides in the context of an ongoing conflict to give the reader a final conclusion, not just fragments of information. Where do these books lead the student to? We have actually sensed in this report a narrative depicting a delegitimized and demonized adversary whose occupation started in 1948 and should end entirely by violent means. Such a curriculum does not bode well to the entire region and the Georg Eckert Institute should have been the first to sound the alarm. Sadly, it has not.

To sum up, the Georg Eckert Institute’s recent report is far from being adequate, although it does follow in the main the general conclusions of its predecessors regarding the rejectionist and belligerent character of the PA curriculum, which surely does not meet the UNESCO standards.