THE SHARDS OF the vessel that was shattered on Oct. 7 are scattered far and wide. They lie in cemeteries; their images look out at us from posters; others who are still breathing are caged underground in Hamas tunnels and in dank dwellings. Their cries, recorded on video by the sadistic attackers, are still being used to damage the souls of their loved ones, friends, and any human being who seeks to coexist with their neighbor.

Putting the pieces back together after a mass slaughter – during which families were burned alive in their homes, summarily executed, women and men raped, dozens of infants and toddlers slain, hundreds and hundreds of young people murdered at a music festival while their attackers celebrated each victim’s death – is not an easy task for a family, a society or a country.

The vessel’s slivers spread quickly to Europe and America and other centers of the Jewish diaspora. On Oct. 7, we gasped at the extent of the barbarity that occurred. In the weeks and months that followed, even the most assimilated Jew had to wonder about the avalanche of antisemitism that took place in our back yards.

On Oct. 7, or that Black Shabbat, as Israelis now refer to that day – while Hamas was still slaughtering Jews and many Arabs and Bedouins – a group of 35 Harvard student organizations announced that it held “the Israeli regime entirely responsible for all the unfolding violence.” They soon took to the streets, labeling Israel as a colonialist and apartheid regime. At Harvard and other schools across the country they held mass demonstrations, forcing Jewish students indoors. When some of the heads of the Harvard protests were identified and their names listed on a truck’s electronic bulletin board in Harvard Square, they pushed back and said it was unfair to identify them publicly.

At UMass Amherst, during a solidarity walk for the hundreds of hostages taken to Gaza, a student approached the group and punched a Hillel participant, and spit on an Israeli flag. In Medford, Tufts Revolutionary Marxists openly stated their “support [for] the Palestinian mass-led overthrow of the colonial Zionist Israeli apartheid state” in an op-ed published in the school’s paper. On the Charles River, the president of the MIT Israel Alliance said that because of the “blatant antisemitism” at the university, she – and most of the other Jewish students on campus – had stopped wearing their Star of David necklaces in public. Meanwhile, when asked during a Congessional hearing if calling for the genocide of Jews violated Harvard’s rules of bullying and harassment, Harvard President Claudine Gay answered: “It can be, depending on the context.”

Gay eventually resigned, but the shaping of a narrative that saw the Oct. 7 attack as a legitimate and justified response to Israel’s existence had already gained ground among GenZ and millennials. By the first week of November, a Harvard-Harris poll reported that 48 percent of respondents aged 18-24 said they sided more with Hamas than with Israel.

That same week, I ventured over to downtown Salem where a group of pro-Palestinians were preparing to march. Even though I had been in the news business a long time, I was shocked at how quickly many Americans had turned on Israel. In Salem, one of the featured speakers was a young person who had emigrated from Ukraine and essentially apologized for being Jewish and having Jewish relatives who live in Israel. Then the group, which included a Buddhist monk who had once enjoyed a Shabbat dinner at my house, began to march through the city, chanting “Free, free Palestine … From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free.”

I wondered if the people at the rally knew that what they were chanting for was the destruction of Israel, since its borders run from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea. I had to ponder if the thousands who marched in capitals throughout Europe and America – and dipped their hands in red paint and placed them on the White House entrance – really understood that their call for a new Intifada meant the endorsement of brutal violence against Israeli civilians. During the last Intifada, over 1,000 Israelis were murdered, including hundreds in suicide bombings.

Each day, the news seemed to get worse. Jews were being spit at, and chased and beaten in the streets; free speech on campuses seemed to be more important than addressing the hate and intimidation that Jewish students endured. In major American cities, including Boston, Palestinian sympathizers ripped down posters of the Israelis and foreign nationals who were dragged into Gaza as hostages. Within weeks, the protesters had flipped the script – the fact that Hamas had started the war, murdered 1,200 Israelis and kidnapped over 250 was all but forgotten.

Instead, Palestinian suffering and the thousands of Palestinian deaths by the Israeli response seemed to be on everybody’s minds. The media – including esteemed major metropolitan publications – made Palestinian casualties the main storyline. Pundits everywhere seemed to come to the same conclusion: Israel was to blame for Oct. 7.

Each week brought more hatred and lies against Israel. As someone who runs a Jewish paper, I could not dismiss this shift in American attitude. But the onslaught of criticism, the accusations of colonialism and lack of recognition of Israel as a historical Jewish homeland began to take a toll. Why was there so much hate, and justification for violence against Israel and Jews? Israel was hardly perfect – it had made mistakes after 1967: perhaps the biggest one was not giving back most of the West Bank and all of Gaza. Palestinians had suffered and were often humiliated during border crossings.

But hadn’t Israel offered up a Palestinian state several times that included parts of Jerusalem’s Old City, and East Jerusalem as a capital, and been turned down by Yasser Arafat and Mahmoud Abbas? (That’s something that Jordan, which occupied the West Bank, and Old City before 1967, never would have done.) I began to feel that the situation was hopeless; that it was an intractable conflict. Unlike the Six-Day War, or even The 1973 Yom Kippur War, there would be no swift victory. Hamas was hiding underground with the hostages in a maze of tunnels that stretched over 350 miles under Gaza.

I worried about my sister and her family, and my friends in Israel. Finally, I did what my soul called me to do: I got on an El Al plane on Jan. 9 and flew to Tel Aviv. I knew I couldn’t change or solve anything. I just needed to be there and witness what the country was going through.

PERHAPS IT WAS the rape, the mutilation of the murdered, the display of unthinkable human behavior that shocked me in the days and months that followed Oct. 7. But somewhere at the center of all my emotions, I had to remind myself that I had been told by Hamas – numerous times – that an attack on Israel was imminent and that its fighters would spare no mercy in their assault.

Over the last 30 years, I have made 15 films on Hamas and its proxy, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency, or UNRWA. In 1995, I interviewed Hamas leader Mahmoud al-Zahar. A former surgeon, he had just finished a lecture to hundreds of Hamas members at the Islamic University of Gaza, and behind his podium was a large poster of a blood-soaked map of Israel, with an image of a knife slicing through the center of the country. After his speech, I made small talk and asked about his family, and tried to find common ties with him. But he only wanted to talk about a Sharia state for all Palestinians and all Arabs in the Middle East, and he kept referring to Israelis as Jews. “The Jews need to leave here and return to Europe where they came from. This is not their land,” he said, during an interview on the dusty campus. When I asked him why the leaders of Hamas did not become suicide bombers and blow themselves up he declined to answer.

In 2006, I spent weeks in Israeli prisons interviewing Palestinians who had committed mass murders. There was Ahlam Tamimi, who accompanied a Hamas suicide bomber to the Sbarro pizzeria in Jerusalem in 2001. Sixteen people died in the blast, including three Americans. When I asked if she felt any remorse about the attack, she smiled and shook her head. “For what?” she said, and then explained that for Palestinians, it was a religious conflict, and that the goal was to kill as many Jews as possible. She was released in a hostage swap for Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit in 2011, and is now a TV personality in Jordan.

There was Abbas al-Sayed, a biomedical engineer who attended college in America. He was found guilty of being the mastermind of the 2002 Park Hotel Passover Bombing in Netanya that left 30 dead (mostly Holocaust survivors) and 140 wounded. He is serving 35 consecutive life sentences for murder. “The mentality of Palestinians now is to see the martyr operation as an altruistic action. For sure, they are heroes. We consider them as heroes, not only as Palestinians. They are considered heroes all over the Arab and Islamic world,” he told me.

And there was Abdullah Barghouti. He is serving 67 life terms for building bombs that blew up the Sbarro Restaurant, Jerusalem’s Café Moment, the Hebrew University’s student cafeteria, and other locations. A total of 66 Israelis were killed in those attacks, and another 500 injured.

He said he was proud of his work, and that there was no such thing as coexistence with Israel. He also told me he wasn’t worried about spending the rest of his life in jail. “I will be out, you will see. I can be out like this,” he said, snapping his fingers.

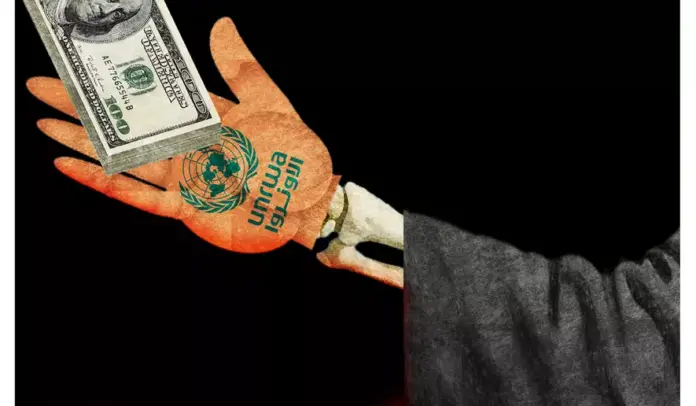

I hurried out of the interview shaken. But in the coming years, I would hear this kind of talk repeated over and over again. In Bethlehem, Jenin and Nablus, children as young as 8 would tell me that they planned to become suicide bombers. Our crew went into UNRWA schools – which educate 337,000 students in Gaza and the West Bank. There, we reviewed curriculum that calls for the violent destruction of Israel. Homework included writing about Dalal Mughrabi, the mastermind of a 1978 bus attack that killed 38 Israelis, including 13 children. Teachers openly taught about the Palestinian “Right of the Return,” a rallying cry of the PLO’s Fatah, and Hamas. It calls for millions of Palestinians to take up residence in villages and towns that their descendents came from before Israel’s creation in 1948. In classrooms, children drew maps of Israel, and identified existing Israeli cities with Palestinian names. Hamas also created after-school clubs to help indoctrinate the students. At the UNRWA Basic School in Gaza, children began the morning with a salute to the Palestinian flag, and a chant: “Glory to a liberated and Arab Palestine. Glory and eternal life for the martyrs, and the righteous. Jerusalem is ours! We will liberate Jerusalem!”

From what I observed, there was no discussion about coexistence or the idea of peace. Instead, kids were taught a noxious mix of religion and politics, along with math and other secular subjects. When I asked kids what they thought of Israelis, they called them subhuman and infidels. “We must kill all of them and Allah will punish all of them,” one boy, who was no older than 10, told me.

About 10 years ago I learned that Hamas was holding summer camps for kids as young as 8. Each July, tens of thousands of children from UNRWA refugee camps were handed rifles and taught how to shoot, kidnap, and kill. Exercises included jumping through circles of fire, crawling under barbed wire, guerilla warfare, and how to best stab and kidnap an Israeli. “I joined to be a warrior, for the sake of Allah; to liberate Palestine from the filth of the Zionist conquest,” one child, who was 11, told us.

In 2015, Osama Mazini, the then-Hamas education minister, praised the children and said they would play an important role as soldiers in the coming years. “They are strong soldiers, proving their potential with Allah’s help,” he said, as he greeted children at the military camp for kids. “You will see them in Haifa and Tel Aviv and on every part of our Palestinian land.” (Mazini was killed during an Israeli airstrike shortly after Oct. 7.)

Over the years, I wondered how long it would take for Hamas to storm the Gaza border. They didn’t seem to be hiding their intentions: their videos of training kids, and simulated attacks and kidnappings of Israelis were all over the Internet. In the meantime, we passed the films along to Israel’s security services and to Knesset members. We never heard back.

After Oct. 7, word began to leak out in the media that Israel had been warned of the attack at least a few times. A year before, Israeli security heads had dismissed a blueprint it had obtained of a planned Hamas border assault as “aspirational.” The plan laid out a scenario that was followed on Oct. 7, and it included drones blowing up video surveillance and remote controlled machine guns at the Israeli border, as heavily armed terrorists blew up parts of the security fence, and stormed the border on motorcycles and in the air, on paragliders. It also included sensitive information about Gaza-area Israeli military bases, which were attacked on Oct. 7.

Last summer, the IDF was warned again about a possible attack. This time it came from an Israeli intelligence analyst who reported that Hamas had just conducted a training exercise similar to the blueprint attack plans that Israel had obtained. The training focused on how to take over a military base and kibbutz.

Her warning was ignored.

Two months ago, Israeli media reported that in the early morning hours of Oct. 7, IDF Chief of Staff Herzi Halevi was warned by the army and Shin Bet that there were signs of an imminent attack by Hamas. While some drones and a combat helicopter were mobilized, Halevi took no further action. In those pre-dawn hours, there were fewer troops than usual at the Gaza border. Hundreds of soldiers had just been sent from the border to the West Bank city of Hawara after a Palestinian was killed while protesting a sukkah that had been set up in the Arab city by nearby Jewish settlers.

“We are in a war, and we will win it,” Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu announced to stunned Israelis in the middle of the attack in a nationally televised address on Oct. 7.

All across the southern border, chaos ensued. Police and emergency lines were flooded with people running from Hamas gunmen and those seeking medical help. Israelis trapped in their safe rooms (bomb shelters) called in to live TV and radio shows, pleading to be rescued. Because terrorists were able to destroy the IDF’s southern command communications system, there was no direct communication with the Kirya, the army’s main command center, in Tel Aviv. Reserve soldiers and retired IDF commanders grabbed weapons and drove toward Gaza; a couple of helicopter pilots took it upon themselves to fly toward Gaza and rescue Israelis. Two all-female tank crews took part in what is believed to be the first women’s tank battle ever, and are credited with saving the lives of many Israelis – flattening terrorists in their path, and shooting Hamas militants who were hiding in trees. Still, there were no Israeli Air Force jets to the rescue. Out of the 1,200 who were killed that day, nearly half were outmanned IDF soldiers and police.

Now, four months later – after over 225 Israeli soldiers were killed in Gaza, and some 25,000 Palestinians (including an estimated 10,000 Hamas soldiers) according to the Hamas-run Gaza Healthy Ministry – Netanyahu has continued to tell the Israeli public that the country can only accept one outcome from the war: total victory over Hamas.

“At the start of the war, I outlined three goals: destroy Hamas, free the hostages, and ensure that Gaza doesn’t pose a threat to Israel in the future. Achieving these goals will ensure Israel’s security and pave the way for additional historic peace agreements with our Arab neighbors. But peace and security require total victory over Hamas. We cannot accept anything else,” he said last week.

Up until 2023, the longest official war Israel fought was its War of Independence in 1948. Now, Netanyahu has presided over the longest continuous battle in Israel’s history, and he believes it could go on until 2025. Critics say

Netanyahu’s goal of “total victory” is unrealistic, since Hamas’s ideology is widely accepted across Gaza, and in the West Bank. His lack of creating a plan for “the day after” the war has alienated President Joe Biden, who has lobbied Congress to pay for Israel’s share of the war and who flew to Israel 10 days after the attack to help reassure a country under seige.

Netanyahu has yet to take responsibility for the attack, and has been unwelcome at funerals and shivas of the victims and soldiers. He has also resisted calls for the IDF to begin an official investigation into the intelligence failure that led to Oct. 7. Polls report that his public disapproval rate has remained at an unfathomable 80 percent since the war began, and each week, more and more Israelis have taken to the streets calling for him to resign, and for new elections.

In numerous interviews, Israelis accused Netanyahu and his government of breaking the country’s social contract twice: failing to protect its citizens on Oct. 7 from Hamas, and failing to bring home all of the Israelis held hostage in Gaza.

Meanwhile, Netanyahu has remained steadfast in his opposition to a Palestinian state – which the U.S. and other Israeli allies believe is necessary to create an eventual peace in the region. His razor-thin coalition is headed by ultra-right wing cabinet ministers such as Itamar Ben-Gvir and Bezalel Smotrich. The two are acolytes of the late Rabbi Meir Kahane, the American-born founder of the Jewish Defense League and former Knesset member who was banned from holding office for his racist views toward Arabs. Ben-Gvir and Smotrich lead parties that hold 14 of the 61 seats needed for a majority to rule Israel, and have warned that they will leave the coalition if Netanyahu enters into peace talks with the Palestinians. Until 2022, Netanyahu refused to be photographed with Ben Gvir – who has made frequent visits to Jerusalem’s Temple Mount – but over the last year, he has looked the other way as West Bank settlers [and Ben Gvir supporters] have rampaged neighboring Arab towns and villages. Since the Hamas attack, former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak likened having the two in such powerful positions to appointing Proud Boys as U.S. Treasury Secretary and Director of Homeland Security.

While he tells Israelis he will settle only for “total victory,” it is unclear how he will achieve his objectives of defeating Hamas and bringing back the hostages without massive concessions – such as releasing thousands of killers like Abdullah Barghouti and Abbas al-Sayed. While polls indicate Israelis would support a deal to bring back all of the hostages – and the dozens of dead Israelis Hamas is holding – Netanyahu is angling for a better deal, and insists that the IDF control Gaza after the war ends. Ben Gvir and Smotrich agree, and recently they joined thousands at a conference to discuss how Israel should resettle Gaza. In total, it was attended by 11 of 16 Israeli cabinet ministers. Critics also accuse Netanyahu of prolonging the war so he can remain in office. [Netanyahu is also facing criminal charges for bribery.]

But cracks have emerged in the country’s five-person war cabinet, which includes Netanyahu, Minister of Defense Yoav Gallant, former Chief of the General Staff Benny Gantz, and two observers, General Gadi Eisenkot and former Ambassador to the U.S. Ron Dermer.

A few weeks ago, Eisenkot, whose son Gal was killed fighting in Gaza in December, accused Netanyahu of misleading the public about Israel’s success in Gaza. “Whoever speaks of the absolute defeat [of Hamas in Gaza] and of it no longer having the will or the capability [to harm Israel], is not speaking the truth. That is why we should not tell tall tales,” he told an Israeli TV reporter.

If Israel eradicates Hamas in Gaza, it will be with a significantly smaller troop base that entered the strip in November. In early January, thousands of troops were sent home so they could resume their lives. Others were relocated to the West Bank and the northern border. “Today, the situation already in the Gaza Strip is that the goals of the war have not yet been achieved, but the war is already not happening. There is a reduced troop deployment, a different modus operandi,” said Eisenkot, of Israel’s war cabinet.

IN A MODEST office building in Tel Aviv, Ehud Olmert also wonders about Oct. 7. He can only conclude that the government and IDF did not believe Hamas was capable of such an attack and did not respect their enemy’s military strength.

“There was an intelligence failure, there’s no question about it. But the failure was not in the collection of information. We had all the information. All of the Israeli systems, the most sophisticated systems there are for cyber intelligence, all of them worked and provided the data,” Olmert told me. “What didn’t work were the minds of the decision makers. Why? Because they did not believe the Palestinians had the ingenuity, the wisdom, the creativity and the power to carry out such a plan.”

Olmert believes that the government needs to be transparent about the IDF’s ability to destroy Hamas and its underground tunnel infrastructure that is estimated to run at least 350 miles under Gaza. He said the IDF had made great strides to reduce the threat of Hamas.

“Hamas is defeated already. Maybe 40 percent of the [Hamas] fighters have been killed. This is devestating,” said Olmert, who is 78, and led Israel during the Lebanon War against Hezbollah in 2006. He served as prime minister until 2009 and also spent 16 months in prison after being convicted of corruption charges.

Olmert said the government needs to make the return of the Israeli hostages held in Gaza its top priority. “There is no greater moral obligation for the people of Israel than to bring back the hostages,” he said. He believes that a long, drawn-out war would not achieve that. “I think it’s time to stop because we need to try and bring back the hostages, and I don’t think continuing fighting will

do it.”

He called for new elections and for negotiations with the Palestinian Authority, which runs Palestinian affairs in the West Bank. He said Netanyahu’s policy of strengthening Hamas – by allowing thousands of Gazans to work in Israel, and millions of dollars from Qatar to pass through Gaza in suitcases each month to strengthen Gaza’s economy – and ignoring the Palestinian Authority, had weakened Israel and its people.

According to Olmert, the biggest threat to Israel could be its lack of vision for the future. “The real danger to the basic foundations of what Israel is all about is the annexation of the territories and the incorporation of 4 ½ to 5 million Palestinians into the state of Israel without human rights, civil rights, political rights, freedom of speech, freedom of movement, and so on. That could be a lot more dangerous to the nature of the basic perception of Israel as a democratic society,” he said.

If anyone knows what it’s like to negotiate with an enemy, it is Olmert. From 2008-9, he met face to face with Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas – also known as Abu Mazen – 36 times. By the beginning of 2009, the sides were close to an agreement. Abbas agreed to a demilitarized state, but wanted 95.5 percent of the West Bank.

“We offered them 95 percent of the West Bank to be part of the Palestinian state and we were prepared to have the Arab side of Jerusalem as their capital,” he told me. Olmert even agreed that the Old City of Jerusalem, and the Temple Mount, would be under the jurisdiction of an international trust, empowered by the UN Security Council, and administered by the U.S., Israel, the Palestinians, Jordan and Saudi Arabia. “We were that close – millimeters – to an agreement, but finally Abu Mazen didn’t have the guts to come and say, ‘OK, I signed it.’ ”

Still, all these years later, Olmert said Israel has no choice but to try to make peace with the Palestinians. He acknowledged that there will be challenges, such as terror attacks and other setbacks. “We have to start again now,” he said. “But for that we need a government of Israel that will be prepared to make these concessions … I’m not sure that the public is prepared to accept the necessary concessions, which ought to be part of the policy and process. But I’ll tell you this. I may not know what the public wants. I think that I know what the public needs, and the role of leadership is to be able to identify the most fundamental needs of the people and to carry out the policy that will lead to that achievement. And I think that this government lacks precisely this.”

Ami Ayalon is the former commander of the Israeli Navy and also served as the director of the Shin Bet, Israel’s internal security agency. He received Israel’s Medal of Valor for saving Israeli Navy commandos during a 1969 battle with Egyptian soldiers. Like Olmert, he does not believe that there is a military solution when it comes to the Palestinians. Moving forward, he said Israel has two options: recognize the Palestinians as a people, and find a way to make peace with them, or wage perpetual war against them.

“In the case of the Palestinians, it is not important what we think about them,” he told me. “They see themselves as a people, and a people who deserve self-determination, and they are fighting for it. Our problem, by the way, is that we see them as people but not as a people. Most Israelis do not think that they deserve a state, especially when we believe that this land was given to us by God many years ago.”

Ronni Shaked, who led the Shin Bet office in Jerusalem and worked as the Arab affairs reporter for Yedioth Ahronoth for 30 years, is now a professor at the Harry S. Truman Research Institute at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He began to follow Hamas in the 1980s, and interviewed its founder, Sheik Ahmed Yassin, dozens of times as he watched the movement gain traction in Gaza and the West Bank. His seminal book, “Hamas – the Islamic Movement,” outlines the history and ethos of the militant theocracy.

He is less optimistic about the prospects of peace than Olmert or Ayalon but agrees that the fighting should stop and that the only positive outcome for Israel would involve the hostages returning home.

“We lost the war on the seventh of October,” said Shaked. “Hamas is not going to raise a white flag. Even if we kill all of Hamas and Yahya Sinwar [the Hamas leader], the only victory can come with the release of the Israeli hostages.”

Shaked, like many other Israelis I spoke with, said the country needs time to process the trauma of the Oct. 7 attack and the Hamas atrocities. He also said that the incitement and Jew hatred Hamas and the Palestinian Authority had helped establish in the home and the classroom had created a culture that encouraged young Palestinians to kill Israelis.

“We are in an intractable conflict,” he said. “The hatred between the two nations will be seven times more than it was before Oct. 7. There’s going to be no trust. Every Palestinian will be seen as a terrorist. Every Palestinian has the vision that Israel will not be on the map. The war will bring a lot of feelings of hatred, hatred will bring revenge, revenge will bring terrorism again. It’s a religious and emotional fight.”

ROUTE 232 IS a narrow, rambling road that begins north of Ashkelon and stretches for 50 miles south to the Egyptian border. For many Israelis in the area, it is known for its emerald agricultural fields and dry river beds that run parallel to sprawling kibbutzim and moshavim, and a few miles to the west, Gaza. On this warm day in January, you can smell the earth as it transitions from the winter rains to the spring sun.

These days, locals call it the Highway of Death. Shortly before 6:30 a.m. on Oct. 7, Hamas began to fire thousands of rockets into Israel. Under the cover of the missiles, Hamas also was able to send drones to Israel’s Erez border, where up until that day 16,000 Gazan residents passed into Israel to work or seek medical attention. The drones blew up Israel’s video surveillance and remote control machine guns at the border. Soon, they breached the fence at more than 30 locations and attacked at least seven military bases where they destroyed the main communications system that connects the IDF southern command with the Kirya, Israel’s national security defense base in Tel Aviv.

By 7 a.m. thousands of Hamas fighters had boldly infiltrated the border on motorcycles, pick-up trucks and on paragliders. They were equipped with machine guns, RPGs, or shoulder fired missiles, hand grenades, land mines and other deadly weapons. They swarmed into the Gaza envelope and blocked a main intersection near Sderot – a city that has regularly been targeted by Hamas rockets over the last two decades. In Sderot, they murdered at least 70 – including 20 police officers, and a group of 13 seniors (many were Holocaust survivors) who were on their way to the Dead Sea for a Shabbat picnic.

Along Route 232, Hamas terrorists overran small communities and military bases, and those celebrating at two music festivals. The militant Islamists even drove as far east as the city of Ofakim – some 18 miles from the Gaza border – where they murdered about 50. By the end of the day, about 1,200 Israelis and foreign workers had been slaughtered, over 5,000 wounded and more than 240 kidnapped to Gaza.

It’s a 17-minute ride from Sderot to Kibbutz Be’eri. There are soft hills on this two-lane road. Before Oct. 7, it was used mostly by locals and trucks that hauled goods to Gaza. These days it’s filled with flashing police cars, IDF jeeps and trucks, and soldiers stationed at entrances to the kibbutzim. The hundreds of burned cars, and bodies found along the road are no longer. The black smears along the highway from the charred vehicles and corpses have faded with the winter rains. And the bomb shelters, where Israelis were murdered by Hamas as they sought shelter, have been painted over.

Still, a grim silence hovers over the road. As we turn into Kibbutz Be’eri, and drive the 450 feet to its main gate, the smell of soot, smoke and death is everywhere. At the entrance, we park in a large rutted lot. As I step out of the car, the ground shakes from an Israeli tank firing a shell toward Gaza.

At the kibbutz gate, a large poster of seven of the kibbutz’s residents who were kidnapped to Gaza flaps in the wind. On Oct. 7, shortly before 7 a.m., video surveillance captured two terrorists at this spot as they crept toward the fence seeking entry to the kibbutz. Seconds later, a car sped toward the entrance. The driver and his two passengers had fled from the nearby Nova concert site, and were seeking shelter from the rockets and terrorists. After the gate slid open, the terrorists shot and killed the three Israeli men in the car. Dozens of Hamas terrorists then moved through the open gate and began their assault.

I don a bulletproof vest and helmet. Hamas is just three miles away in Gaza, and still shooting rockets toward this area.

We are led by David Marcus, an IDF major, who grew up in Michigan and tells me he has hopes that the Lions will reach the Super Bowl one day. Our other guide is Maya, who is 24, and managed a Tel Aviv restaurant up until Oct. 7, when she reported to the IDF reserves.

The kibbutz and its side roads have the feel of a small development in California or the Southwest, and its perimeter is lined with a tall chain-link fence topped with barbed wire. Some 70 residents have returned since Oct. 7, and work in its printing press – one of the country’s largest. About 10 percent of the 1,000 who lived here before the attack were murdered. Hundreds are still housed in temporary rooms at hotels at the Dead Sea.

Just the night before, residents had come together to celebrate the kibbutz’s 77th anniversary. But for the next 18 hours, the community would be the subject of a brutal attack where up to 200 Palestinians terrorized the population at will. They executed residents point blank, burned families alive while making their loved ones watch, tortured men and women, mutilated their bodies, and sexually assaulted women and men – young and old. They set fire to more than 100 homes, and slaughtered residents when they came running out of the front door. Over 50 bodies were found in the back section of the kibbutz known as the Vineyard and Olives neighborhood.

Save for the birds, and the tanks firing into Gaza, the kibbutz is silent. It is hard to stroll here, knowing that unthinkable atrocities took place on this patch of land. We walk to a group of small homes where families have been living since 1946.

Vivian Silver, who was 74, lived in a modest cottage not far from the main gate. She grew up in Winnipeg, Canada, and had been a peace activist since the 1970s when she made aliyah. Silver had lived at the kibbutz for 33 years, and was the director of the Arab Jewish Center for Empowerment, Equality, and Cooperation. She had many friends in Gaza, and often drove Palestinians who needed medical assistance to Israeli hospitals.

Soon, we are led into Silver’s house. After the attack, she was listed as kidnapped because her body was not found in her home or on the kibbutz. But in mid-Nov., traces of her DNA confirmed that she had been burned alive in her house.

Walking through her home is like entering a fireplace. There is black and white ash everywhere. The walls are coal-black and cracked, soot rises up some four inches from what’s left of the floor, and footprints dot the monochrome powder. A few charred appliances – a stove, a microwave and a sink – sit mangled in what was once a kitchen. The safe room – which was built to withstand bombs but not terrorists, and did not have a lock on it – is barren, save for the ash and its four scorched walls.

“It was burned severely, as many of the bodies were burned to the extent that there was no remains,” Maya, the IDF spokeswoman, told me when I asked her where Silver’s body had been found. “We had to bring in special teams of archaeologists to identify what we could. At times, all that was left was teeth. So this was a similar case, and it took a month and a half to identify the body … bodies were burned to ash but you have no way of knowing if people were shot to death and then burned or burned alive.”

We leave Silver’s house, and walk past her neighbors’ homes. All were set afire and their sagging, blackened walls and roofs are slowly collapsing. I ask Maya how the war has changed her life. “I don’t think we even know how deeply its changed but it has changed immensely. We’re currently in survival mode, I think, if you ask anyone,” she tells me as we approach the main entrance to leave. “There are people who have lost their loved ones, people who have experienced great loss – and again, you can’t fully begin to grasp or understand that this even happened, even to the people it happened to.”

Back out on Route 232, there’s little traffic as we approach Kibbutz Re’im – the site of the Nova rave festival. Re’im, which means “friends” in Hebrew, was built in 1949. Like it’s neighbor, Be’eri, just a nine-minute ride away, Re’im is known as a left-leaning community that favors peace with the Palestinians. One of its main sources of revenue comes from its laser factory, Isralaser.

Our car slows, and the main entrance is guarded by an IDF tank and patrol, and closed to the public. That’s the road that was captured in a drone video clip hours after the attack, showing hundreds of burned cars and the scorched earth that Hamas left as a reminder of its presence.

An IDF soldier waves us toward another entrance to the site about 100 yards south. There’s a ditch on the side of the road that leads in – too deep for most cars to quickly pass through– and those escaping from this opening on the morning of Oct. 7 probably cursed the hole in the ground.

How does one approach the site of one of the worst massacres in modern day Jewish history? There is a dissonance here with the beauty of the grounds and the brutality of the crimes that were committed on this land. When you walk you can feel the moss and leaves crunch below your shoes, and the setting sun spills out a palette of orange and pink and red. If one was unaware of Oct. 7, and the massacre here, it would be easy to have a picnic under one of the trees, and a laugh. But no one laughs here anymore. Thoughts cease on these hundreds of acres. Eucalyptus groves stand guard over the grounds; birds sing their afternoon lullabies. There is an ineffable emptiness here. You don’t see ruins, you don’t see the burned cars anymore – it’s all in your imagination for a moment. And then you remember the barbarism that took place on this property.

It is here that visitors must remind themselves that they can’t change anything. They can’t do anything for the hundreds and hundreds of victims or for those taken hostage. It doesn’t help to think about the Hamas attackers either, who blocked the exits and laughed as they blew up motorists and those who had been dancing minutes earlier with shoulder-fired missiles. At least 360 were murdered here, and dozens were dragged off to the tunnels of Gaza. Some were gang-raped by Hamas gunmen and then shot to death. Most of the victims were people under 30 who had sought “peace and nature” as the festival had advertised.

If there is a mass Jewish graveyard in the world now, it sits here at this site, just a few miles from Gaza. At this kibbutz, as many as 3,000 people gathered for a three-day electronic music festival that was slated to end on Oct. 7. Now, it is holy earth where people whisper when they speak. It’s about the size of a Little League baseball field. On this patch of earth where people were dancing shortly before the attack began, a memorial of 360 faces and dozens of others who were kidnapped look out at visitors. So many people were killed here that each memorial has two photos of victims to accommodate the murdered.

Most smile. A woman in a white sundress beams as she looks toward the sky. A girl in her twenties looks exuberant as she stares at us from a restaurant. An auburn-haired woman with sunglasses laughs from a field of red and orange carnations; a millennial with thick glasses and a warm smile is bundled up in front of a mountain filled with snow. A bare-chested body builder raises his arms after winning an award. A woman clasps her hands together in prayer and seems to say namaste. There’s a photo of a smiling Hersh Goldberg Polin, who lost an arm that morning of the attack, and is believed to be held in Gaza. And there are large banners strung between trees urging us not to forget those taken by force to Gaza. RELEASE ME! reads one, which shows a large photo of Guy Gilboa-Dalal, who was wrestled away by Hamas on these grounds.

Each memorial has its own message, it seems, and more than anything the pictures suggest a tribe that seemed happy and liked to travel, and party. The monuments are well kept, and crushed stone gardens share space with flowers, small plants, yahrzeit candles, notes from loved ones, hamsas, and Israeli flags. At the site’s entrance, a pop-up tent has been set up as a temporary synagogue. Afternoon minyans and the mourner’s kaddish continue until after sunset. Every few minutes, dozens of visitors arrive, and others leave.

Everybody seems to be here for the same reason. We’re looking for answers; we’re seeking solace. We’re trying to figure it out. We wonder: how is it possible that man could do this to one another? We are the secular, the religious, those who believe in God one day, and are not sure the next day. We sleepwalk in a circle around the memorial, our eyes dazed, staring, acknowledging, hoping we haven’t missed anything.

A bus filled with soldiers is parked behind the memorial and the men and women fan out to pay tribute to the victims. Some are limping; they were in Gaza and were injured. Many kneel down to the bottom of memorials and light yahrzeit candles. Most are silent, and wipe away tears.

Yaakov, a soldier who had served in Gaza the previous month, had just spent 30 minutes finding memorials for friends who had been killed at the site. A machine gun slung over his shoulder, and he waved me away after a short conversation. “I feel a lot of anger, and that’s it,” he said. “I knew 15 people here. All of the 15 were killed.”

Another soldier requested anonymity. “It’s hard for me. My two best friends were murdered here. I’m in a lot of pain now. But it’s good that I came here because I feel connected,” he told me.

“It’s really harsh,” added Noy, a Tel Aviv attorney and IDF soldier. “You know, you look at everything around here and it’s green and beautiful. And for one minute it’s easy to forget what happened here. Then you see all of those photos of smiling innocent people who were actually my age. It’s kind of a living cemetery. I knew one person from the town I grew up in. She was murdered here.”

The faces of the victims are the hardest for people like Yarin Ilovich. “When I see them I give each one a kiss and a hug,” said Ilovich, a psytrance artist who was the last DJ to play music at the festival before the rockets were fired from Gaza. He said 100 of his friends were killed that day.

Ilovich, who lives in the coastal town of Herzliya and is known in the trance world as Artifex, was playing music on the stage in the early morning hours of Oct. 7. “It was the best event I played. It was the best stage. Everybody was having fun and filled with joy. And the sunrise was amazing. Everyone was so pumped and people were dancing and smiling and the energy was really magical,” he said.

At 6:29 a.m., he was playing a psytrance remix of the artists Pixel and Space Cat. Then he saw the rockets overhead and stopped the music. “It went from the best day of my professional career to my worst day,” he said. “It was an apocalypse. Terrorists attacked you, friends died near you. There was blood and screaming and shooting everywhere. It was a doom day. It was like everything was dead.”

After trying to drive out of the lot, he abandoned his car and starting running with a friend. Eventually they reached Israeli police on Route 232, who were in the midst of a shootout with the terrorists. “They told us to get under the police car and we stayed there for four hours until we were evacuated,” he said.

Keeping busy helps him blot out the memory of that day. He recently helped organize an exhibit in Tel Aviv from the Nova festival – where remnants from the massacre, such as burned cars and tents, clothes, shoes and almost everything else that was left at the site was put on display for the public. “I go to a therapist and I stay busy and it’s a good busy. When you’re busy your mind is not running backward, only forward,” he said.

As the sun was going down, the faces from the memorial continued to smile. Michal Avital, and her daughter Tamar, who live in nearby Moshav Yesha were looking for their cousin’s memorial. Michal, who works as an architect, was still in mourning. Her moshav – which is nearby the Nova site – was also attacked on Oct. 7. She spent the day with her family in her safe room but emerged after she learned that her older brother had been murdered by Hamas. Like tens of thousands of other residents near Gaza, she had to leave the moshav right after the attack since it was not safe to remain. Tamar had gone to Utah to stay but had just retuned. It was Michal’s second time back at the moshav since Oct. 7, and she wanted to leave some flowers at the place where her brother had been killed.

As she walked through the sea of faces, she realized that three other friends from her moshav had been killed at the rave. “I’m upset, I’m angry, I’m hurt, disappointed,” she said. “It’s very painful to see all of these faces. Some of them I knew, and suddenly you see the pictures. It’s horrific.”

She lamented that the pastoral countryside kibbutz was now a tragic chapter in Jewish history. Something had changed for her along Route 232. “This is where we run all of the time, twice a week. I run 10 or 15 kilometers,” she told me. “This is one of the most beautiful places in the area. We wait for this time of year to run. We used to run around Be’eri, and Re’im.”

THEY CALL THIS place Hostages Square. It sits on a concrete pavilion in front of the vaunted Tel Aviv Museum of Art, and is located across the street from one of the entrances of Israel’s national defense building – the Kirya. If there is a place in Israel that represents the collective emotions of the nation, it is this sprawling courtyard. Here, grief and hope coexist – sorrow that has fallen on Israel since Oct. 7, and a resolve that serves as a default for a nation determined to move forward and heal.

On Saturday, after Shabbat ends, there is heartbreak for several hours at Hostages Square. On the nights I attended, more than 100,000 were sandwiched in between the narrow streets that separate the world of art and culture – and now desperation. Here, the people long to put the country’s social contract back together, and implore Israel’s decision makers across the street to make a deal to release the hostages.

Upon arrival, the first thing you notice is a long wall of the kidnapped who are still in Gaza. Here, more than 130 faces stare back at the visitor – many are smiling in their photo; all would tell a harrowing story if they could talk. These hostages are the ones that Hamas refused to give up in early December when Israel agreed to release 240 Palestinian security prisoners for 105 hostages, including 80 Israelis. While most of the liberated Israelis were women and children, Hamas refused to release the youngest hostage, Kfir Bibas (who was kidnapped when he was eight-months-old) and his brother Ariel (who is four), and mother Shiri (Hamas insists that they were killed in an Israeli air attack). In addition, they are still holding at least 16 women – including five who are under 20 years old, who were taken from military bases. Another 95 are men who served in the IDF, including seniors in their 80s.

The faces of the kidnapped at Hostages Square are sacrosanct, and here visitors are mostly silent. Some touch the images; others write notes or draw hearts and butterflies; some seem to whisper prayers to the wall. Unlike large European and American cities where progressives and pro-Palestinians have ripped down posters of the Israelis, these images are considered holy and represent a pool of anguish that continues to spill forth from Oct. 7.

On these streets, nearly everyone knows someone who was kidnapped, or a relative of the kidnapped, or someone who was murdered or injured on Oct. 7. And they know how their fellow Israelis have been treated by Hamas. Released hostages have reported that they were held in cages, in total darkness, given a morsel of rice to eat each day if they were lucky, and faced psychological and sexual abuse. Hostages released after two months in Gaza lost an average of 10 to 15 percent of their body weight in captivity. At Knesset hearings last month, Aviva Siegel, who was taken by Hamas and released in the exchange in November, testified that Israeli women were being treated like sex dolls. “I saw it with my own eyes,” said Siegel, whose husband Keith is still being held by Hamas.

“I felt as if the girls in captivity were my daughters. The terrorists bring inappropriate clothes, clothes for dolls and turn the girls into their dolls. Dolls on a string with which you can do whatever you want, whenever you want.”

“Many girls underwent severe sexual abuse,” added former hostage Chen Goldstein Almog, who also testified that some of the women had stopped menstruating and may be pregnant. “They had serious and complex wounds that were not being cared for.”

Hostages who were released reported not showering since Oct. 7, and having to wait hours to use the bathroom. Some children were told their families were dead and ordered not to speak during their captivity. “You sleep and you cry,” said Danielle Aloni in a video. “Every day that passes is like a never-ending eternity.”

Of the 136 Israelis kidnapped, the IDF believes that at least 31 are dead.

Shortly after Shabbat ended on Jan. 13, a sea of Israelis carrying signs of the kidnapped filled Hostages Square. There, sisters Shani and Inbal Ronel held signs with the image of David Cunio, and demanded his release.

“I’m here to express the pain of one of my best friends, Sharon Aloni Cunio. She is married to David Cunio,” said Shani, who along with her sister, grew up with Sharon in Yavneh. “They were abducted from their home with their twin babies on the seventh of October. Sharon was brought back on the fourth day of the deals with her daughters but they were all separated from David and she cannot move on and get better with him back there. We owe it to them and her family to bring him back.”

In an interview on Israeli TV last month, Sharon Aloni Cunio described her life today as “hell,” and said the last time she saw her husband he was wearing a short-sleeved shirt and shivering in the cold. “I’m stuck. I’m on hold. For me, life didn’t go on from the moment they separated me from David. The girls are throwing tantrums, things they never had [done] before Oct. 7,” she said.

At the vigil, Sharon’s sister Danielle Aloni spoke to the crowd on the 100th day of the war. Danielle and her five-year-old daughter were also kidnapped and eventually released in November. She addressed world leaders, and yelled, “How would you feel if your women were being raped, how would you act if they were shooting at your parents, if they were burning your beloved ones?”

U.S. Ambassador to Israel Jack Lew also took to the stage. “We will not stop working to bring them home. From President Biden, on down, the United States is determined to get back all of the remaining hostages,” he said. When he told the crowd that the hostages needed to return home and added the Hebrew word achschav, or now, the crowd began to chant, achchav!

About 200 feet from the stage, Adina Fender stood with friends and family. She had moved from France 12 years earlier, but until Oct. 7 she never felt fully Israeli. Soon after the war began, she returned to Paris with her children but feared for her safety in her native country.

“My first instinct was to take my children and actually go to Paris. And then I got to Paris and felt very alone. I felt like people could not understand me, and that people didn’t care. I felt attacked and threatened on the streets of Paris. So I was very happy to come back here and I thought, maybe it’s war but at least I’m not alone, and we’re in the same boat with fellow Israelis and Jews here,” she said.

“As a mother of Jewish children I feel like it could have been me, it could have been any of us. I feel like it’s really important for us to come and show support to the families. We care about their loved ones and remember them and we support the efforts that are being made to bring them back.”

On the sidewalk across the street from the large screens that showed the speakers and stage, Becky Kempinski sighed. She had spent Shabbat with her parents and was on her way back to Netanya but decided she had to stop at the vigil. “I came out here because of pain. This is very painful,” she said. “People there [in Gaza] are in huge distress and I feel we’re all connected to it because it really could have been each and every one of us there. Like everyone else, I feel deeply connected and I feel like we need to support the families as much as we can.”

During weekdays, thousands of people visit. On this footprint, families of the hostages have been sleeping in tents for much of the last four months. During that time, art installations have been set up to help Israelis process the mass kidnapping and torture.

One can purchase a chain that hundreds of thousands of Israelis wear daily that implores the government to “BRING THEM HOME NOW!” At booths, friends of the hostages and their families make small talk with visitors, and also sell T-shirts and sweatshirts that have the same message. Yards away, a long Shabbat table stretches for over 100 feet. On one side, the linens and plates are blue and white, in Israel’s national colors – representing the hostages that have returned. On the other side, the tablecloth is gray and dirty and there’s a speck of rice on each aluminum pan. There are no utensils and water bottles stand cloudy. On each seat is a poster of a hostage in silhouette, with the words, “BRING THEM HOME NOW!”

A grand piano sits nearby on a stage, and every few minutes someone plays a sad melody. To the rear of the square, over 100 yellow chairs have been chained together, and above the seats a poster reads “Achschav!” A few steps away, a replica tunnel similar to the ones where hostages are being held by Hamas, has been erected. Israelis slowly move through the structure, which broadcasts the sounds of guns and bombs. Inside the tunnel, the faces of the kidnap stare back at you, and Israelis scrawl notes to the photos.

Tents line the property, and they are filled with friends and sometimes relatives of the hostages. They come from all over the country to sit in these huts – some survived in their kibbutz and moshav safe rooms; some are soldiers, and policemen who want to pay their respect. Some are survivors of the Nova music festival.

Some, like Dana Sapir, took it upon herself to try to impart what the female Israeli hostages were going through. She wore a dirty white shroud, smudged with red – to reflect the sexual assault the hostages have endured – and for hours, she was locked in a small cage where she could barely move. On her hands were written the message, “Over my dead body.”

Eliya, a musician from Jaffa, makes her way to Hostages Square nearly every day. “It’s the only thing I can do. I’m very depressed. I just watch the news and come here, and these are the only clothes I want to wear – clothes I bought here, that support the kidnapped. I don’t want to wear anything with color, or that’s happy. I just want to wear the clothes of grief.

“My mom’s best friend lives in Nir Oz and her father, and mother and three nephews were murdered. One girl who worked with me was in the Nova festival,” said Eliya. On Oct. 6 she said she made lunch for two workers from Gaza who were fixing a wall in her apartment.

Eliya and her mother are the only Jews who live on her block in Jaffa. To date, she has never had any issues with her neighbors. “I know Arabs. My landlord is an Arab, my doctor is an Arab,” she said. She was hopeful that peace could come one day, but only if the Palestinians stopped teaching their children to hate Jews. “Now there’s a lot of zombies that have been created by brainwashing.”

Vova, who works as a psychologist in Kfar Saba, said he had to visit the site because he couldn’t stop thinking of Kfir Bibas, the boy who was turning one that day in Gaza. “Yesterday was my grandson’s first birthday and he’s just one day older than Kfir Bibas. And I just couldn’t stay home. I had to come here,” he said. When asked what his patients were feeling since Oct. 7, he replied, “I believe we just have a post-traumatic society here.”

IT’S UNCLEAR HOW many Israelis have been impacted by the trauma of the war. According to Dr. Ido Laurie, over 500,000 Israelis could have Post Traumatic Syndrome Disorder. The Mayo Clinic defines PTSD as a mental health condition that’s triggered by a terrifying event – either experiencing it or witnessing it. Symptoms include flashbacks, nightmares and severe anxiety.

“The good news is that most of the people will heal,” said Laurie, who is the director of the Adult Outpatient Clinic at the Shalvata Mental Health Center in Israel. According to Laurie, who is trained as a psychiatrist, PTSD treatment can include psychotherapy, medication and Eye Movement Desensitization Reprocessing therapy, or EMDR.

Laurie also said that over the last year, the country has seen a 45 percent increase in reported anxiety disorders, an increase of 25 percent in psychiatric treatment in clinics and mental health centers, and as much as a 20 percent increase in the purchase of anxiety anti-depressants and sleep medication.

“We had to invent new structures that we never thought we would need to invent,” said Dr. Gilad Bodenheimer, who explained the emergency actions taken after Oct. 7. A psychiatrist who heads Israel’s Mental Health Services at Israel’s Ministry of Health, Bodenheimer gathered about 150 therapists to assist families who came to identify the dead after the Hamas attack. “All these people, whether it was relatives who came to identify the bodies, the Army soldiers who evacuated the bodies, and then the religious authorities like Zaka who picked up body parts – all of these people needed to speak to connect.”

In addition, his team made 30,000 calls to people who were impacted by the attack, and offered mental health assistance.

It’s unclear just how many new patients have enrolled in therapy, but the country’s leading therapists say that tens of thousands have requested mental health assistance. Bodenheimer said about 4 percent of the country was enrolled in therapy before Oct. 7. Since then, his organization has set up resilience centers across the country – and in cities like Eilat and at hotels in the Dead Sea. There, about 25,000 of the country’s estimated 200,000 residents from the southern and northern borders who were evacuated are sleeping in hotel rooms.

Right after Oct. 7, Dr. Talia Kotter drove down to Eilat. She was one of the first child psychiatrists on the scene, and helped treat the victims and survivors from the Southern Israel’s Eshkol region who had been bussed to the hotels. One of her first tasks was working with survivors who had to deliver the news to other survivors that a family member had been killed.

She said that most of the victims and children would eventually recover if they have a strong support system and good role models. “Some will need long-term therapy, some will need more short-term and then long-term watching,” she said. “Most of us are much more resilient than we believe.”

Bodenheimer is also optimistic that many of the hostages will recover. “Recovering does not mean you do not have bad memories or you do not suffer from symptoms that stay there. I believe the hostages will always have bad memories and will always have this or that symptom that we will need to deal with. The issue of recovering from trauma in my eyes is the ability to rehabilitate, to keep on with life, to be able to function,” he said.

IN THE AMPUTEE wing of Tel HaShomer Hospital outside of Tel Aviv, the hallways are jammed with visitors bringing sandwiches, cakes and cookies to injured soldiers and their families. When the man in the wheelchair learns that there is a reporter from Boston he flashes a bright smile. “I love Boston,” he tells me.

“You know Boston?” I ask.

“I spent 16 summers as a camper at Camp Ramah in Palmer. My mother worked for the Jewish Agency and would take me every year,” he says, and then introduces himself as Yoav.

Four days after he turned 30, Yoav was watching the sunrise with his girlfriend in Nueba, an Egyptian beach on the Red Sea that’s been popular with Israelis since the 1970s. It was Oct. 7, and as he sipped his morning coffee, a jogger mentioned to him that Israel was being hit with a barrage of missiles. He looked at his phone, and saw that southern Israel was under attack. In a matter of minutes, he paid the hotel bill, summoned a taxi, and by 9 a.m., the couple had crossed the border at Eilat. By 8 p.m. that night he was in uniform at his army base.

Over the years, Yoav has worked as a flight attendant and most recently as a security guard. But he has always seen himself as a soldier, first. Trained as a combat medic, and a sharpshooter, he has been part of the same commando unit since 2013. “I am part of a team of around 18 men that I consider my family. They are like my brothers,” he said.

He had taken part of Operation Protective Edge in Gaza in 2014, and by the time his unit entered Gaza in early November this year, he began to recognize the terrain. On Nov. 20 he and his squad were in Southern Gaza when they noticed heavily armed Hamas soldiers.

“Me and my team were chasing these terrorists down the street. And we entered a very narrow street. There were five of them. We managed to kill three. They were running around with AK-47s and RPGs; there was no way that you could mistake them for civilians. So they were trying to hit our tank. We wanted to catch the other two. And they went into a house that had like a big garden around it,” he said.

Meanwhile, Yoav and his friend Tzvika waited outside for his group to clear the building. “And then someone shot an RPG missile that hit right between us. And I remember flying in the air, and I landed on my back. And I saw that my leg, was you know, crooked. I saw a bone and I saw my foot in a crooked positon. And the first thing that I think about is the next hit because the natural response to an RPG is another RPG a couple of seconds later,” he said.

A medic from his squad immediately performed a tracheotomy so Yoav could breath, and also opened a hole in his lungs to clear out all of the air and blood.

As he was airlifted in a helicopter, Yoav lost his pulse and a doctor thought he had died. The pulse came back, and that’s when Yoav realized that he had lost part of his leg. Since the RPG attack, he’s had 30 surgeries and still has months of rehabilitation to go. “I lost my leg. I lost my hearing in my left ear. My vocal chords were damaged. I broke my elbow. My lungs are better now but they don’t have the same capacity as they used to have,” he tells me.

I ask how he’s processing all of this.

“I was lucky, because I’m an optimist. The glass is half full. I took the lemons and I made lemonade. I really think that things happen to us in life, and it is our decision on how to take them and how to approach them. You know, I might have lost my leg, but hey, I’m still alive. I wasn’t supposed to be alive after that. Some doctors told me that they looked at my situation in the field and they thought I wouldn’t make it to the hospital. And I wasn’t supposed to make it to the hospital.

“Now, I’m processing an event like this and it’s going to sound weird what I’m about to say: It’s very hard but very easy at the same time. It’s very easy because that’s what you have. This is what you have. This is it. This is the hand that you were dealt with. And this is the hand you’re gonna play with – this is it, it’s not going to change. So that determination helps you realize it. You know, it was a punch in the face, but that’s it, you know, it’s like, alright, this is what I have to deal with now. And this is what I’m going to do. And the difficult part is thinking about the things that you can’t do anymore, right? The main one is the fact that I can’t fight anymore. I can’t be a warrior anymore, which is who I am. This is what I do. So I feel like a big part of my personality was taken away from me. But there might still be hope because I’ve seen people that are fighting and they have a prosthetic leg.”

Yoav strongly supports the war, and believes Israel’s response was necessary. He said that during the house-to-house combat, he regularly discovered weapons hidden under children’s beds. “I found AK-47’s, RPG’s, pistols, submachine guns, heavy machine guns, M-16’s, grenades and other explosives. We found tunnels that connected to the houses – a lot of tunnels,” he said. “You think to yourself, like, how badly do these guys hate us? Like how poisoned are they against us?”

Yoav doesn’t think that it’s possible to eradicate Hamas because its ideology can’t be destroyed. But he believes Palestinians should have the option to live in a democracy if offered that opportunity.

He also thinks a lot about the Israeli hostages.

“I think that the first thing that we need to think about is to bring the people that are kidnapped back home, no matter what. Even if we have to appear as the losing side for once,” he said. “We need to bring them back. This is what we need to do. There’s no other choice. All the rest is just water under the bridge.”

IN A NONDESCRIPT mall tucked away on a side road 20 minutes north of Tel Aviv, Ronen Koehler walks from room to room methodically, mentally checking off a to-do list that is impossibly long. In the 7,000-square-foot office, he helps run Brothers and Sisters for Israel – the country’s largest humanitarian aid organization.

Koehler, a reserve Israeli Navy officer, was one of the leaders of the protest movement that engulfed Israel last year. The movement, then known as Brothers in Arms, was started by active and former IDF reservists and high-tech leaders who opposed Netanyahu’s plan to overhaul Israel’s judicial movement. They believed that handing so much power to a single prime minister or political party would quickly erode Israel’s democracy. Over a period of nine months, about 100 different groups from across Israel would join Brothers in Arms, and each Saturday night more than 100,000 would gather at a main protest in Tel Aviv – while thousands of other Israelis held demonstrations in Jerusalem, Haifa and other cities. At one point last summer, some members of the group said they would not fulfill their military reserve duty if the judicial changes moved forward.

But on Oct. 7, the organization shifted its priorities and became a humanitarian nonprofit. Well organized and with a database of over 70,000 names and emails, the group’s leaders sent out an email that day encouraging all IDF reservists to report for duty. Almost immediately, the group realized that it could fill roles that the overwhelmed government could not. Within a day it had raised about $6 million. Soon, 15,000 Israelis had volunteered to help the group. These days the group has raised about $30 million, with half of the donations coming from outside of the country.

“We just said we’re going to help,” Koehler said. “We started getting calls from people saying, ‘we’re stuck in our secured room. Can you take us out?’”

The group of former officers then set about extracting and rescuing over 100,000 Israelis who were not safe in their homes near Gaza, and also on the Lebanese border near Hezbollah.

It helped secure military vests and helmets for the IDF. It helped build bomb shelters. It helped train civil defense groups. And one of its first initiatives was establishing a center to identify and locate missing and kidnapped Israelis.

Within two days, about 400 people were working around the clock using artificial intelligence facial recognition technology. By then, the government visited and told the group that it would take them weeks to establish a similar operation.

“They started to bring us data, and they had data from the body cameras of terrorists,” said Koehler. Soon, they were able to identify 200 hostages.

In the weeks and months that followed, the organization and its volunteers worked to fill a massive void in social services. It distributed hundreds of thousands of meals, 40,000 units of medical equipment, set up logistic centers to assist displaced citizens, distributed 100,000 pieces of life-saving military equipment and helped thousands of Israelis obtain immediate mental health care. These days one of its main focuses is creating dozens of temporary schools for as many as 15,000 kids who were displaced.

The group is also determined to distribute as many life-saving medical kits as possible to first responders and medical professionals. Those kits include everything a doctor or an emergency medical technician or a nurse needs to save a life – such as tourniquets, bandages, intubation kits, and more.

“What we realized is that it took a long time – a much longer time than we were used to – for the wounded to get to the hospital [on Oct. 7]. And many people died because they didn’t have enough medical supplies and enough medical teams in the field. And what we have decided, is that there is a need to train people, medical teams, and to provide the equipment for them to be able to help in case of another catastrophe,” said Dr. Hadar Raz, who worked as a battalion combat physician and now leads the Brothers and Sisters first line medical program.

As I prepare to leave, I see kids scampering in a large room. “That’s a school for kids who were evacuated,” Koehler says.

Then Koehler points to a simple chain and dog tag around his neck. It reads, “BRING THEM HOME NOW!”

He unclasps it and then places it around my neck. Tears well up in my eyes. From that moment on I wear it every day.

AT NIGHT I walk down the wide streets of Tel Aviv. One evening, I order an Israeli salad and hummus at a packed restaurant on Dizengoff Street. People smile, some even laugh. For a minute I forget that there’s a war going on, and then my eyes drift to a park bench a few feet away from my outdoor table. There’s a poster with the photos of the women still held in Gaza, and another sign below which reads, “The horror of denying rape is terror.”

One night, I connect with an old friend from Jerusalem. “I’m going to a party. Want to join me?” he asks.

We drive to a restaurant and I wonder what kind of party it will be. We climb the stairs and reach a small dining room on the second floor that looks like a wine cellar. About 10 people are in the room and I assume they all know each other but it turns out most are meeting for the first time.

“I created this meet up group so people could make friends and connect,” Rachel Cohen explained. Cohen, who is 49 and once lived in Philadelphia, moves through the room like a kindergarten teacher, and makes sure everyone has met. She has a wide smile, and exudes the confidence of a TV talk show host.

Within a minute, everyone is chatting away like they’ve known each other for years. Yitzhak, who sits next to me, quickly learns that he works in the same building as Yafit, who sits opposite me. Yafit tells us that she has five children: Avraham, Yitzhak, Yaakov, Sarah and Rivka. “Everybody’s going through this bad situation now,” Uriel, an Internet marketing executive, told me. He had lived in Manhattan for 15 years but said it never felt like home. “It’s good that we can share and find a peaceful moment together.”

Another night, I hop on the new subway not far from Hostages Square and head toward Jaffa. The ride takes 20 minutes, and soon I am eating knafeh. It’s a delicacy in these parts – a dessert with a shredded filo dough crust, cheese filling, and topped with a sugary rose-water-flavored syrup. I amble around the downtown and along Jerusalem Street – the main boulevard – and wonder about Jonah, who was swallowed by a whale off of these waters.

The same night I stumble upon a dance for seniors. Inside, over 100 people are out on the dance floor, swinging to ’70s music.

I realize it’s OK to dance, even during a war.

I THOUGHT I knew a lot about Israeli culture but it turns out I have a lot to learn. I’ve visited often, lived in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, and have lots of friends and family here. I have returned almost every year because Israel offers something I can’t find anywhere else: acceptance. Even during war, there’s a sense of security here – a feeling that the nation is unified; a sense that the person sitting opposite you on the train is not a stranger.

Minutes after meeting someone for the first time, I repeatedly find myself locked into long conversations with people I will probably never see again. Sometimes there are tears about the war, about relatives and friends and loved ones who were killed on Oct. 7. Sometimes I find myself hugging a person, or receiving a hug from someone who tells me something deeply personal.

A nation that was so divided last year about the proposed judicial change – with some calling it a civil war – has shifted its narrative. Millions of Israelis are now plugged into a unity grid. People rush to volunteer and help others because it feels so much better to give than receive. They listen more. It seems like the manifestation of the Hebrew term, “Ahavat Yisrael,” – which roughly translates into “Love your fellow like yourselves” (Leviticus 19:18.) That term is repeated often in Jewish circles in the U.S., but doesn’t accurately describe our community. Here, though, it rings true during these dark days.

Amid the uncertainty of war, there is a hope across this nation that I have never witnessed. It’s a resilience, a determination, an understanding that Israel will survive no matter what obstacles and violence it might face.

“One picks oneself up and lives,” Professor Ilan Troen told me during a phone interview after I asked how he was doing. Troen, who grew up in Boston, is the Lopin Professor of Modern History, emeritus, and a founding director of the Kreitman Foundation Fellowships at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. He is also the founding director of the Schusterman Center at Brandeis.

On Oct. 7, his daughter Deborah and son-in-law Shlomi were murdered in their safe room at their kibbutz near Gaza. Before she died, Deborah fell on her son to protect him from the terrorists. Troen spent much of the day texting his 16-year-old grandson, assuring him that he would survive.

“The hope is, is that they will rebuild their kibbutz. The hope is that we will squash, we will inhibit, we will disarm and disable Hamas from doing what they’ve done in the past and were doing again. And we hope that the Arab communities will correct themselves and together, we can do what we both need to do in order to live together,” he said.

In Tel Aviv, former Prime Minister Ehud Olmert called the country’s civil society extraordinary. “This is the greatest expression of solidarity that you can find anyplace in the world. And this is the inner strength of Israeli society, more than anything else – more than the military, more than the intelligence, more than the Mossad, more than the army, more than anything. What binds us together is a sense of mutual responsibility and solidarity. Which is unique. Absolutely unique.”

Dr. Gilad Bodenheimer, the psychiatrist who helps run the country’s Health Ministry, said that the war proves that Israelis need one another. “We really learned that we need to help each other because no one else will help us if we won’t help each other. And that’s something in our DNA. It’s very, very structured in how we are raised and how we are taught, and in everything we do,” he said.

On my way to the airport, I try to hold on to this solidarity. How long it will last is unknown. There are problems in the Promised Land. Israel’s allies are demanding a Palestinian state. But who would lead it, and would it even recognize Israel? Could it drop its antisemitic rhetoric and see Israelis as human? And could Israel recognize the Palestinians as a people? Could the two sides take a leap of faith?

All of this seems like a far-away dream. But I hold on to the smiles, the grief, the unity, and dare – for a second – to wonder what peace might look like one day in this land of war and hope. Θ

Steven A. Rosenberg is the editor and publisher of The Jewish Journal of Greater Boston. Email him at rosenberg@jewishjournal.org.